New Ireland - Tabar Islands - New Guinea mermaid

Gary Opit

Is this the New Guinea mermaid, a new species to western science? Photo: Wesley Lyonagi

Mystery sighting in 1973

From August 1973 to December 1974 I dwelt amongst the living wonders on the world’s largest tropical island, New Guinea, studying the flora and fauna with biologists at the Wau Ecology Centre, lecturing on ecology at the Lae teacher’s college and living with stone-age tribal people. Between the 2nd and the 7th of October 1973 I was travelling on the Papuan Explorer, a 340-ton vessel carrying cargo along the northern coast of Papua New Guinea between Lae & Vanimo, delivering supplies & a few passengers to Wewak & Aitape. During the 5-day voyage I spent much of my time identifying the marine life that included large fish sharks, rays, spinner dolphin and sea birds.

On the third of October around midday I observed directly in front of the bow a round brown head on the sea surface that looked more human than anything else. At the approach of the vessel the head suddenly submerged straight down beneath the water as if it had pulled itself under using its flippers and tail. I was standing near the bow and as we passed over the animal I obtained a clear view as it sank vertically through the crystal-clear water two to three metres below the surface. I saw a round head and an elongated human-sized body and I wondered if it may have been a dugong. The body was slim, unlike the bulky shape of a dugong. Dugongs raise their broad snout and head to just above the ocean surface where the two nostrils inhale air and then they propel themselves forward and dived headfirst. This marine mammal descended tail-first and I was unable to conclude as to what the animal was.

Pishmary - the mermaid

Talking to an elderly New Guinean man from a coastal village near Aitape on his knowledge of the local fauna, he described a marine mammal that he had only once encountered. He and a friend were fishing off the coast in their dugout canoe hauling up their net and they brought to the surface an unfamiliar animal somewhat like but different to a dugong and which they released. He told me that it was not a dugong because they regularly caught and ate dugongs and that this was quite a different animal altogether. Eventually I found that in the Papua New Guinea national language of pidgin English, this marine mammal is known as the Pishmary, meaning fish-mary or Fish-woman, (Mary being the word used for women).

The Pishmary, or mermaid. Photo: Wesley Lyonagi

Other local names

Eight years later I was amazed to read that others had also encountered the New Guinea Mermaid. In Volume 1 of Cryptozoology, the Interdisciplinary Journal of the International Society of Cryptozoology 1982 there is a paper written by Roy Wagner, Head of the Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia, entitled The Ri - unidentified Aquatic Animal of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea. Wagner was studying the culture of the local people from 1979 to 1980 when he discovered that they were all aware of a scientifically unidentified marine mammal. People in Barok used the name pronounced “ah ree” for this animal. People in Susurunga used the name “ilkai”. These island fishermen were aware of the other marine mammals and stated that the ri or ilkai was quite different to the dolphins, porpoises, pilot whales and dugongs, the latter known as bo narasi in Barok meaning “pig of the ocean” because of its fat body, rounded whiskery face and vegetarian eating habits.

Distribution

From the accounts of the local people Roy Wagner found that the New Guinea Mermaid is distributed around the shores of the Bismarck Sea, the Solomon Sea and the Pacific off the shores of the Bismarck and Solomon archipelagos. They are particularly distributed around the central and southern shores of New Ireland and the straits between the islands of Buka and Bougainville in the Northern Solomon. The ri or ilkai also exists further west around Manus Island and off the north coast of New Guinea where fisherman have caught them in nets at Aitape. Roy Wagner found that the ri or ilkai were well known long before the arrival of Europeans and that like all species of animal that co-exist with them they hold a special place in their culture & they have cultural stories that explain their creation.

Cultural significance

Roy Wagner was shown a ri swimming in Ramat Bay on the eastern coast of New Ireland though all that he could see was a long dark body swimming horizontally at the surface several hundred metres away. A village magistrate told Wagner that whilst fishing out at sea, he had observed a Ri rise to the surface & look at him from only about 6 metres away. He claimed that he had also once observed a male & female ri mating in the surf. A 10-year-old boy described to Wagner how he had once observed a line of male, female and juvenile ri swimming up into a freshwater stream by moonlight. Furthermore, that it was a common sport for schoolboys, during the December – January vacation, to dive offshore with glass face-masks to catch glimpses of ri.

Physiology and behaviour

Wagner found that people living on the islands of Lihir and Siar occasionally killed ri for food and he interviewed many men who had witnessed the butchering of the animals and had eaten their flesh. They commented that ri have “a great deal of blood, like a human being, and their body fat is yellow”. When Wagner asked whether there were vestigial leg bones in the lower extremity of the body, they replied that the skeletal structure of the tail consisted only of an elongation of the spine.

In Volume 2 of Cryptozoology, 1983 there is a Field Report entitled Further Investigations into the Biological and Cultural Affinities of the Ri by Roy Wagner, J. Richard Greenwell, Gale J. Raymond and Kurt von Nieda, which describes a scientific expedition between mid-June and mid-July 1983 led by Wagner back to New Ireland to determine whether the ri really was an unclassified marine mammal. They returned to Namatanai to obtain further information on the ri that had been butchered and eaten and located a Western-trained medical orderly who had witnessed the event and stated emphatically that the animal was not a dugong. Villagers talked of ri entering the rivers at night from the sea to fish in very shallow water. After exploring Ramat Bay without success, the team were informed that ri were being sighted almost daily at the village of Nokon, 50 miles to the south.

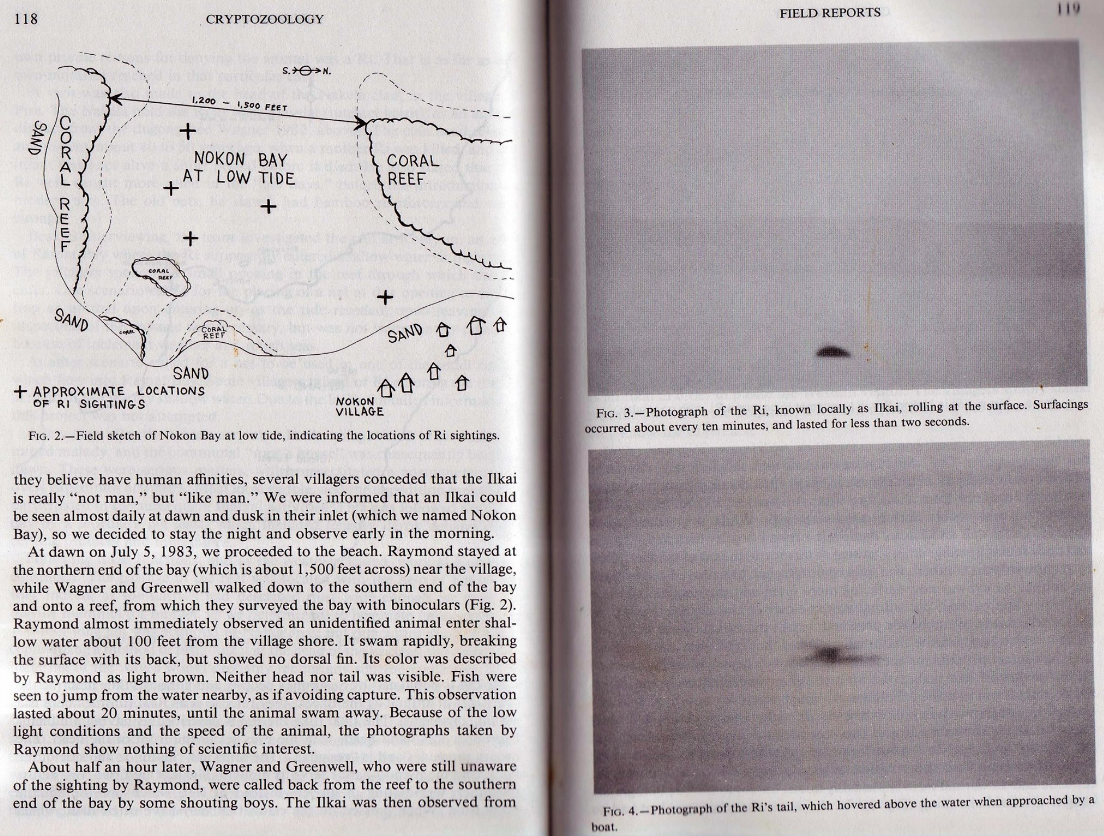

The Susurunga people at Nokon used the name ilkai to describe the same animal & described it as having the eyes set to the front of the head. The mouth was described as protruding and peculiar. At dawn on 5 July 1983 members of the team could view the ilkai as it apparently hunted fish in shallow water 100 feet from the shore. For 20 minutes it swam rapidly, breaking the surface with its back, which was light brown in colour and showed no dorsal fin, and fish were observed to jump from the water to avoid capture. It was next observed repeatedly diving in deeper water 300 to 400 feet from the shore and appeared dark and slender. It surfaced every 10 minutes with a sharp roll, indicating extreme vertical flexure. The team approached within 50 feet of the ilkai and observed that at times it kept its tail flukes above the surface of the water and photos were taken before it submerged without reappearing.

No further observations were obtained at Nokon or at Huris on the opposite side of Cape Natanatamberan though they received reports from the village people of sightings of ilkai at both these locations while the team conducted its searches. On 12 July two members of the team observed the same animal rolling at the surface in bright sunlight and it appeared to be tan to light green in colour. At no time was the head ever observed.

A 1983 cryptozoology report on the "Ri", a local name for what has become called the New Guinea mermaid. Photo: Gary Opit.

Identification

All the marine mammologists consulted after the team returned home agreed that the animal was new to science. The zoologists concluded that the animal’s rapid movement, consistently extended duration of submergence, its consistently extreme vertical flexure and its predatory behaviour eliminated the possibility that it was a dugong or sea-cow. Nor was it a species of finless dolphin (Wagner et al 1983).

New Ireland local Wesley Lyonagi recently took photographs of a marine mammal that he could not identify and posted them on his Facebook page and wrote “This is the rare and unidentified mammal which became a friend to this small boy, on the second pic just at the end of its tail. This small boy introduced his friend (mammal) to his families. Can anyone really identify to me the scientific name for this mammal?” This was then shared & posted on the Australian Mammal Identification Facebook site by Vicky Narere. Vicky Narere wrote that the animal was encountered and photographed by local people in New Ireland around the Tabar Islands. Could these be the first photographs ever taken of Wagner’s ri or ilkai, the pishmary (fish-woman) or New Guinea Mermaid?

It is natural to assume that this is just a dugong but there are some interesting angles to consider. I explored much of New Ireland in 1974 and all of the tribal people are inhabitants of the coastline and are reliant on sea food for much of their diet. An uninhabited mountainous interior covered in forest runs through the centre of the island with unique species such as the enormous blue birdwing butterfly, one of the world’s largest species and a long-tailed drongo bird. The people are expert fisherman & know all the sea creatures so it seems strange that they cannot identify a species such as the dugong. The photos of the dugong in this posting are those that I took of two captives in the Sydney aquarium, some of the only captive dugongs in the world.

It is worth making a comparison of the dugong’s head and body compared to the mystery marine mammal’s head and body. The dugong’s head forms part of the streamlined body with no neck and the wide snout of the dugong is the same width as the head. In the mystery mammal, the head and body are separated by a neck and the snout is narrower and smaller than the head. The mystery marine mammal has a narrow body near the tail with a raised backbone unlike the dugong where the backbone is hidden by the thick streamlined body & remains quite thick until it teaches the tail flukes. Some people have wondered if it is a manatee, however manatees live only in the Atlantic Ocean while dugongs live in the south western Pacific Ocean and the northern Indian Ocean. In the album of photos included with this post are the photos taken by Wesley Lyonagi, a page from Volume 2 of Cryptozoology, 1983 Field Report Further Investigations into the Biological and Cultural Affinities of the Ri by Roy Wagner, J. Richard Greenwell, Gale J. Raymond and Kurt von Nieda & photos that I took of a dugong at the Sydney aquarium for comparison with the mystery marine mammal.

A dugong (not the New Guinea mermaid) at Sydney Aquarium for comparison. Photo: Gary Opit.

The "New Guinea mermaid", possibly a new species to western science. Photo: Wesley Lyonagi

Addendum - historical accounts identified as dugong

Chris Rehberg

Following this article going to press, there was further discussion on the Australian Mammal Identification Facebook group.

Mike Playfair noted that "Roy Wagner and the late Richard Greenwell investigated and positively identified it as Dugong dugon" in the 1980s. Markus Hemmler clarified "Two years after 1983 another article followed. Thomas Williams and Co. wrote "Identification of the Ri through further fieldword in New Ireland, Papua New Guinea" in Cryptozoology 4, 1985. Dugong dugong." Dr Karl Shuker verified "it was conclusively identified in the ISC's journal paper as a dugong."

All the above lends weight to the prospect that the mystery animal from New Ireland may well be an emaciated dugong, and one further consideration that may support this is to ask how this wild animal came to be under the hands of those in the photos if it were otherwise in perfect health?

In response, Gary notes that while the 1985 animal was identified as a dugong, this conflicts with local accounts of the ri which are said to eat fish (as described above). If the animal in the above photographs is an emaciated dugong, there still remains the possibility of an unidentified fish eating mammal.