Blaeu thylacine - 17th century Tasmanian map shows striped animal dated 1659

Chris Rehberg

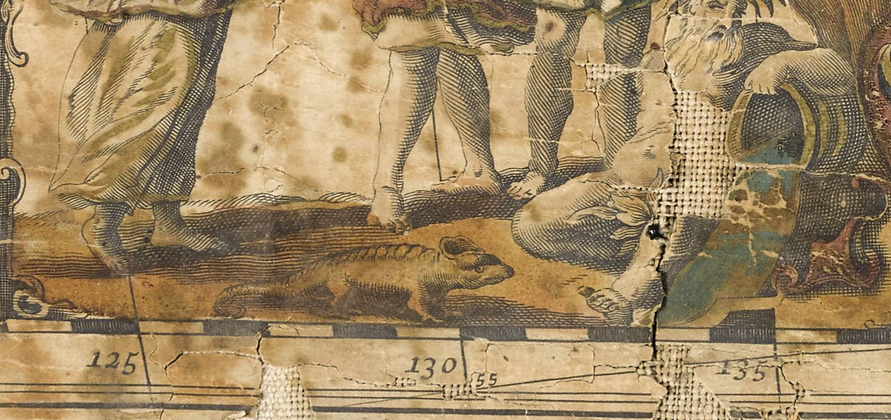

Detail from the 17th century map. Image copyright: Sotheby's. Used with permission.

Overview

In May 2017 news broke that the world's oldest known surviving map to name Australia "Nova Hollandia" had been discovered in an Italian residence, where it had been since at least the 1800s. It is also the earliest map to show Tasmania - then named Van Diemen's Land - along with the Australian mainland.

The map itself dates to 1659, making it almost 360 years old at the time of its discovery. It is believed there are two versions of this map in existence, the second being a print dated to 1663, according to Australian Geographic.

Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu produced the work on the basis of Abel Janszoon Tasman's expeditions to the region in 1642 - 1643 and 1644.

The map

Full map

The photograph below shows the full map. The northern, western and part of the southern coastline of mainland Australia is visible. Below this, the southern half of Tasmania's coastline is visible.

17th century map by Joan Blaeu showing coast of Australia. Image copyright: Sotheby's. Used with permission.

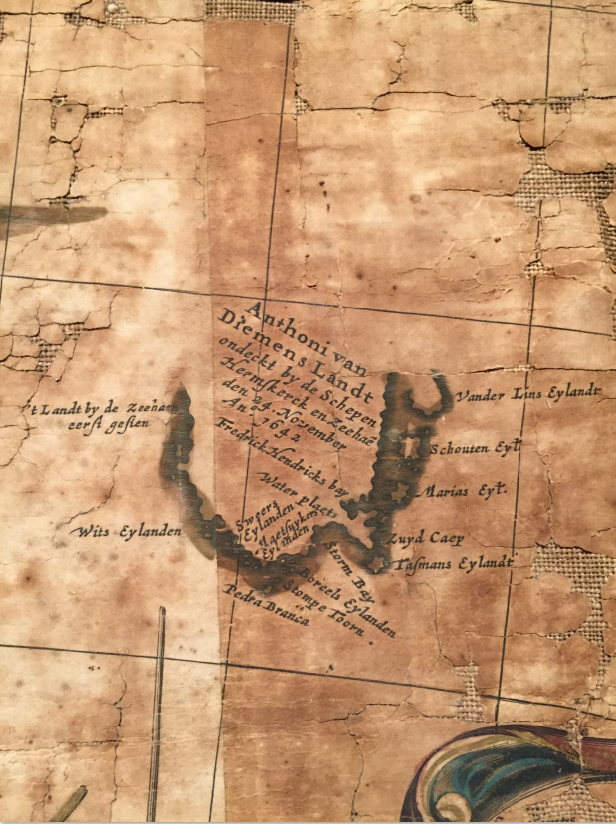

Tasmanian coast

The image below presents a detailed view of the Tasmanian coastline on Blaeu's map.

Detail of 17th century map by Joan Blaeu showing coast of Tasmania. Image copyright: Sotheby's. Used with permission.

The landmass is titled (with some characters transcribed from the original):

- Anthoni van Diemens Landt ondeckt by de Schepen Heemskerck en Zeehae den 24. November An 1642.

This translates roughly as:

- Anthony van Diemen's Land, sighted(?) / landed(?) by the ships(?) Heemskerck and Zeehae on 24 November in [the] year 1642.

An interesting note off the west coast says:

- 't Landt by de Zeehaen eerst gesien

This seems to imply that land - ie. Tasmania - was first seen ("eerst gesien") by the ship Zeehaen.

The following place names are all labelled:

| Map text | Translation | Possible present-day correlations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wits Eylanden | Wits Islands | De Witt Islands; Alternatively, Mutton Bird Island, Sugarmouse Island, Sugarloaf Rock, Wendar Island | Two islands bear the name "De Witt Island" off the Tasmanian south coast in Google Maps. Both are to the east of Maatsukyer Island (listed below) but in Blaeu's map, "Wits Eylanden" is shown to the west. The alternative list of islands given here is the nearest significant collection of islands to the west of Maatsuyker Island and is located near a prominent headland, similarly to Blaeu's map. |

| Pedra Branca | Pedra Branca | Pedra Branca | Pedra Branca is a rock islet of 6.2 acres some 26km from the Tasmanian mainland shoreline. While important to many marine wildlife species, it is especially notable for being the only known range of the Pedra Branca skink. |

| Sweers Eylanden | Sweers Islands | ? | |

| Maetsuykers Eylanden | Maetsuykers Islands | Maatsuyker Islands | This group of islands and rocks is the site of Australia's most southerly lighthouse. |

| Stompe Toorn | ? | ? | |

| Boreels Eylanden | Boreels Islands | ? | Presumably the name of this island group, "Boreels" translates to "Borealis" in modern English. The "Aurora Borealis" is a night sky phenomenon visible in Earth's Northern Hemisphere, whereby streaks of light appear. A similar phenomenon is visible in the Southern Hemisphere, including from Tasmania, and is now named the "Aurora Australia". It is possible this island group was named for the place at which the explorers first observed the Aurora Australis in Tasmanian waters. |

| Storm Bay | Storm Bay | Storm Bay | Storm Bay is a large bay containing Bruny Island. Tasmania's capital city, Hobart, lies on the shores of Storm Bay at the mouth of the Derwent River. |

| Water Plaets | Fresh Water | ? | It is likely this label of "Fresh Water" describes the presence of fresh water moreso than names a specific body of water. Its location on the map at the northern edge of Storm Bay is in the vicinity of the Derwent River. |

| Tasmans Eylandt | Tasman's Island | (South?) Bruny Island? | Although Tasmans Eylandt appears off the coast at "South Cape" (see below), there is no such landmass there. However Tasmans Eylandt is the largest island noted off the south coast of Tasmania - which matches Bruny Island. |

| Zuyd Caep | South Cape | Cape Pillar, approximately (ie. Port Arthur region) | Although named South Cape, this major peninsula is not the southerly most part of Tasmania's coast; neither does it appear to be the most southerly part of Blaeu's map. At the time of Tasman's expedition it may not have been known that Bruny Island was in fact separate from the Tasmanian mainland. In this case, South Cape, on the map, may correlate with South Bruny Island. The problem with this interpretation is that there is no other significantly large island off southern Tasmania to match that labelled "Tasmans Eylandt". That said, Pedra Branca on the map, at 6 acres is clearly disproportionate as it appears to be twice the size of Maatsuyker Island which is, in fact 186 hectares. |

| Marias Eyt. | Maria's Island | Maria Island | Maria Island is, today, a site of significant cultural and historical importance. It also plays an important part in wildlife conservation by having an offshore population of Tasmanian devils to combat against devil facial tumour disease (DFTD). |

| Schouten Eyt. | Schouten Island | Schouten Island | Schouten Island lies off the Freycinet Peninsula on Tasmania's east coast. |

| Vander Lins Eylandt | Vander Lins Island | Freycinet Peninsula | From Tasman's ships off the shore of Tasmania, it is easy to understand why Freycinet Peninsula was presumed to be an island as they sailed north around the peninsula. |

Wikipedia notes that of 200 place names given by the Dutch to Australian localities in the 17th century, only about 35 remain today.

Title box

The title box on Blaeu's map is richly illustrated with animal and human figures.

Detail of 17th century map by Joan Blaeu showing title box and illustrations. Image copyright: Sotheby's. Used with permission.

No less than nine human figures are visible: four at left, three of whom are standing and one reclining; four at right mirroring those at left with three standing and one reclining; and a single female figure at top.

Various tools and instruments are visible, including spears, a fishing pole, a staff and basket.

Several animals are also depicted with some quite closely resembling animals that are recognisable today, while others are more ambiguous. Apparent among these are:

- A pig, atop the title box.

- A flightless bird the height of a person, to the left of the title box, which fairly resembles an emu. Emus are native to Australia and were formerly distributed in Tasmania.

- The head and forequarters of what is likely an ungulate stepping out from behind the right hand side of the title box.

- The hint of what might be a camel in the background near the ungulate.

- A small mammal resembling the pig, of identical proportions, foot form and pose which is likely a piglet, at right in the foreground.

- And a small, rather curious striped creature in the foreground, at left. It is this small creature which is perhaps most difficult to correlate to any known species and it is this animal that is the subject of this analysis.

The striped animal

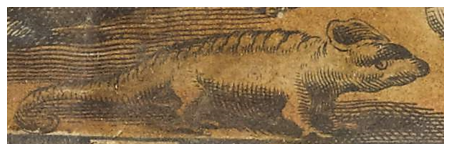

The image below shows the unknown striped animal in detail.

On close inspection of this animal, the following features stand out:

- Its tail is curved at the end.

- There is a series of transverse stripes along its back - certainly from behind the neck and onto its rump; possibly onto its tail, although in this region the line-work is similar to shading on other areas of the animal.

- Its feet appear to have at least one rearward-facing digit.

- Its head is rather nondescript...

- ... Except for some attachment, protrusion or decoration at the top of its head; other than this unusual feature there is no indication of external ears.

Thylacine?

Could this creature really be a representation of the thylacine from Tasmania? If so, then no specific text description is known to exist from Tasman's voyage. Many of its features (notably its tail, feet and overall body shape) suggest something more akin to a lizard or other reptile. It is notable that the pig illustration clearly has fur while fur is not apparant on this unknown animal. It must be borne in mind that Tasman's expeditions, and the map itself, span all the way from Tasmania in the south, through to southeast Asia in the north covering areas rich in animal diversity.

However before discarding the possibility of Tasmanian tiger, there is merit in reviewing at least one of the earliest visual depictions of that species.

Early historical illustrations of the thylacine

Carol Freeman's book Paper Tiger, published in 2014, looks at historical depictions of the thylacine and the ways in which these depictions shaped public and scientific opinions on the species. It collates a large number of early illustrative works, one of which is considered here. Arguably the least life-like early illustration of the thylacine is an 1856 engraving by Dr Chenu whom Freeman notes as "a notoriously inaccurate naturalist".

For comparison, Dr Chenu's engraving is depicted here (in mirror image) beneath the unknown animal from Blaeu's map

The unknown animal from Blaeu's map (above) and the 1856 engraving of a thylacine, in reverse, by Dr Chenu (below).

The animals have the following traits superficially in common: curled tails, squat hind legs and posture, general body proportions, and ears, if we take the unknown feature of the unknown animal to represent the outline of its ears. Both animals are striped in a manner equally vague with respect to an actual thylacine. Different between the illustrations however, are that Dr Chenu's animal is clearly furred - including with whiskers - with at least four digits on each hand or foot, and the positions of their eyes.

While the similarity between these illustrations is, at best, superficial, the point here is that Dr Chenu's illustration is labelled as representing the thylacine and yet deviates incredibly from the actual animal. Blaeu's unknown animal is no more unrealistic than Dr Chenu's and does - superficially - contain key features of a thylacine.

Conclusion

Could Blaeu's unknown animal illustrate the Tasmanian tiger?

In favour of the possibility are the facts that:

- Other animals on the map are reasonably realistic, including one that may resemble the Australian emu; the unknown animal is the only one with no clear correlation.

- Early artists (and certainly many more than just Dr Chenu) produced unrealistic (though typically more recognisable) depictions of the thylacine, primarily because they were working from second-hand descriptions of the animal. Bear in mind Blaeu produced this map some 17 years after Tasman's ships first sighted Van Diemen's Land.

- The map notes fresh water on Tasmania and historical accounts verify the crews of Heemskerck and Zeehan made landfall on several occasions. Although there is no known textual documentation of having sighted a thylacine, it is certainly possible one was seen.

Against the possibility are the facts that:

- There is no known written record of a thylacine being sighted during these expeditions.

- The map and expeditions covered many other landmasses, including present day Indonesia and Madagascar, and only one of the other animals is prospectively Australian.

- The animal is sufficiently vague in appearance that it could match any number of other species.

- The other animals on the map are relatively to scale with respect to the people; if this animal is to scale then it is rather small for a thylacine.

Much like the animals in Margaret Preston's artwork of a drought stricken Australian landscape, the animal in Blaeu's map is almost certainly not a thylacine. Perhaps the best match for a known species is a chameleon:

Chameleon published by Lianne McLeod at thespruce.com, attributed to GettyImages

The similarities here are clear: the curled tail, leg posture, rearward facing digits (not visible in this photo) and, in this species, a head crest. In this case the chameleon is also striped although chameleons are able to change their colour. Even without stripes, a ridge line of bumps is observable along its back.

It is certainly likely we will never have the definitive answer on Blaeu's intent with the mystery striped animal.

Detail from Blaeu's map. Image copyright: Sotheby's. Used with permission.