Cameron thylacine - detailed analysis

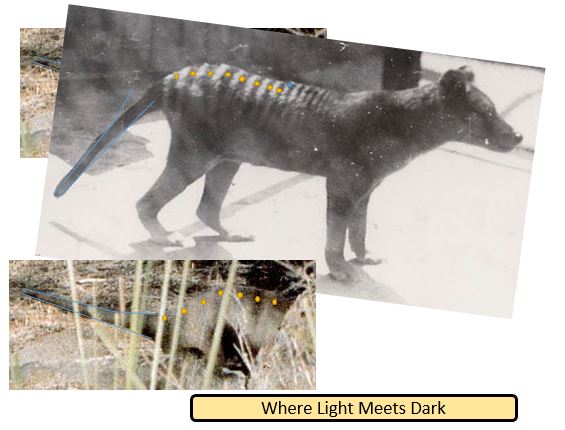

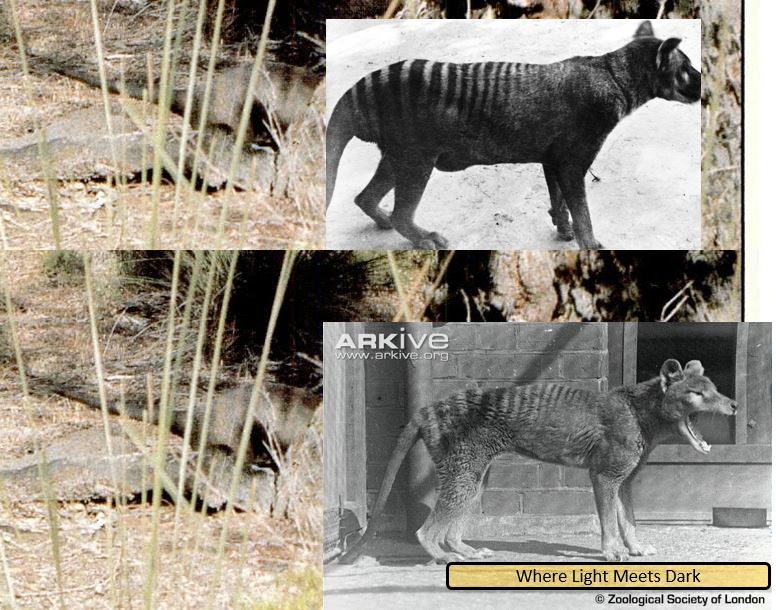

Cameron thylacine Photo 3 overlaid on a zoo photograph.

Overview

In 1984 Aboriginal tracker Kevin Cameron was contracted to search for the Tasmanian tiger in Western Australia in response to ongoing sighting reports made by the public. After a period of 3 to 4 months Cameron produced a set of five photographs showing the rear of an animal matching the appearance of a thylacine. These were published by Athol Douglas in New Scientist magazine in 1986 and responses to the article were mixed. Some readers and experts, including former director of Taronga Park Zoo in Sydney, Dr Ronald Strahan, stated the animal is clearly a thylacine while others argued the markings on the animal did not match what is expected of a Tasmanian tiger.

Complicating matters was the allegation that the set of photos must have been taken over a period of hours. This was argued on the grounds that shadows from trees had moved significantly from one frame to the next. Yet despite the time passing, the animal remained stationary. With its head obscured from view in every photo, and the presence of a rifle in one frame, this in turn led to speculation that the animal was dead - whether freshly killed or a staged specimen.

In February 2018 this author had the opportunity to discuss these events and the photographs with Kevin. In this article we take a look at the question of the identity of the animal, whether the photographs support the back story and examine each of the criticisms leveled at the photographs.

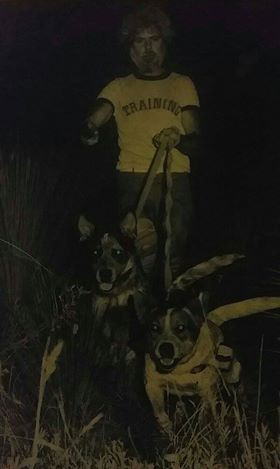

Kevin Cameron with his two dogs Sam (at right) and Lobo. Photo courtesy: Kevin Cameron. Used with permission.

The photographs

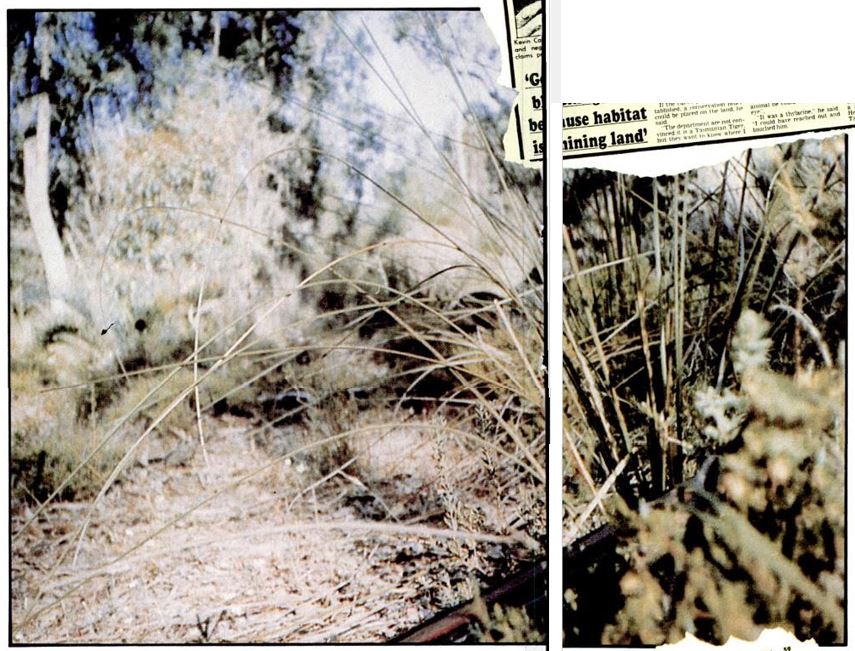

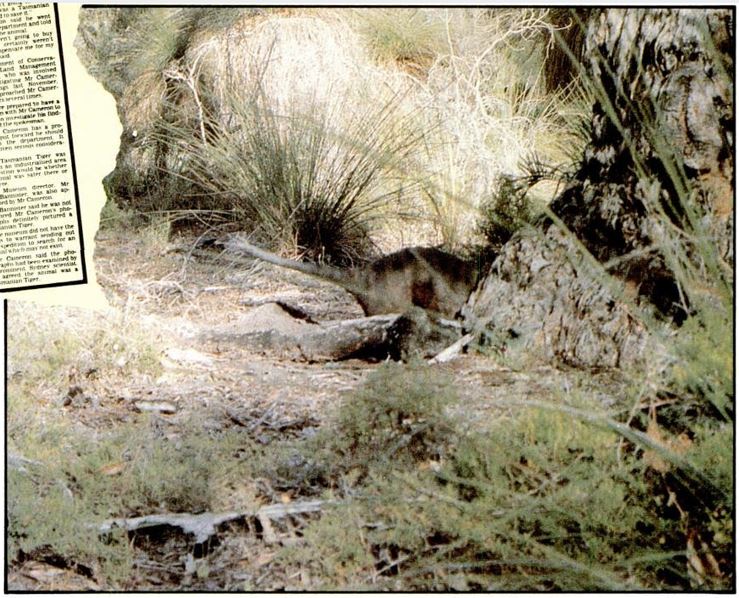

The account of Cameron's thylacine was first published in New Scientist magazine, 24 April 1986. The full text is available as a Google Books preview and includes three of the five photographs. These three photographs are reproduced here.

Photo 1

Composite image of Cameron thylacine Photo 1. Source: New Scientist. Photo: Kevin Cameron.

This photograph is spread over two pages in the original magazine - hence the vertical white band through the image where the magazine pages meet.

In New Scientist, the photograph is captioned "Kevin Cameron's photographs were taken as he approached the thylacine. The first [photo] ... shows his discarded rifle in the foreground, with the putative thylacine just visible in the centre of the picture".

New Scientist goes on to say "The first photograph shows the thylacine in the distance, with Kevin's discarded rifle in the foreground. The remaining four were taken at intervals as Kevin approached, the last being from only metres away. The thylacine was busily digging at the base of a tree, its head down behind the stump, and it was only because it was so engrossed that Kevin could get as close as he did. Although normally wary and alert, this animal was at a disadvantage because the stump obscured its vision, and the noise of its digging masked Kevin's quiet approach. It was only the click of the shutter on the final photograph that alerted the thylacine, which bounded away."

The article goes on to discuss plaster casts taken by Kevin although it is not clear whether these were from this animal or other tracks he had found. The article says that Cameron had seen thylacines on at least four separate occasions.

In the photo above, the rifle is clearly seen lying in the foreground. Although the article states the thylacine is just visible at centre of the frame, this is not easy to discern. The author's interpretation of this is guided by a subsequent letter to the New Scientist editor and a tentative interpretation of where two key elements - visible in the other photos - are seen in this picture.

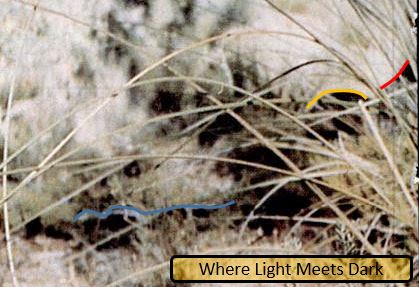

Excerpt of Cameron thylacine Photo 1 showing tree trunk (red), thylacine's back (orange) and foreground branch (blue).

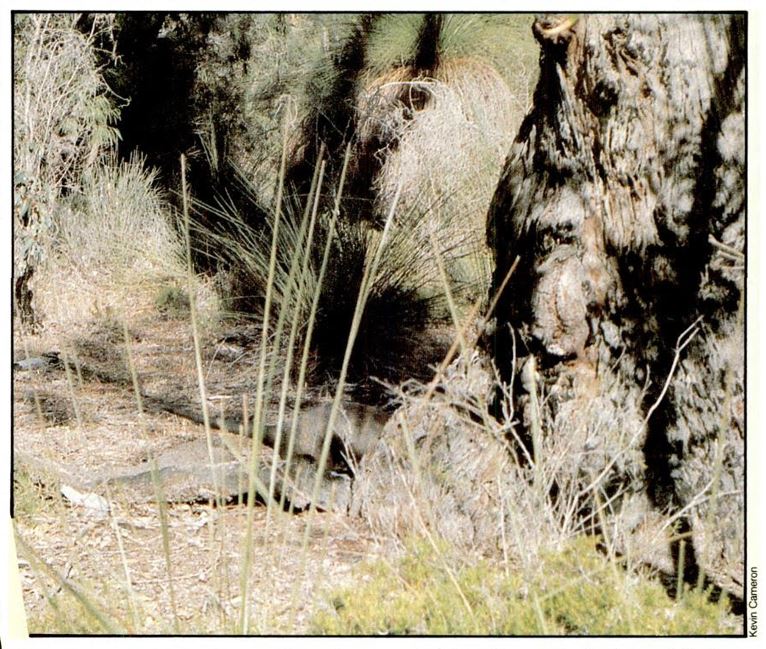

Photo 2

Cameron thylacine - Photo 2. Source: New Scientist. Photo: Kevin Cameron

The animal is clearly visible in this frame. As noted above, the animal is described as digging behind the tree. The excerpt below has been traced to illustrate the position of the thylacine.

Excerpt from Cameron thylacine Photo 2 - illustrating location of the thylacine in the photo.

Photo 3

Cameron thylacine - Photo 3. Source: New Scientist. Photo: Kevin Cameron

The third photograph shows the thylacine in much the same position as in Photo 2. The excerpt below illustrates the position of the thylacine in Photo 3.

Excerpt from Cameron thylacine Photo 3 - illustrating location of the thylacine in the photo.

One of the criticisms of Cameron's photographs is that the shadows of the trees appear to have moved great distances between shots, implying considerable time had passed between shots. On first glance this appears to be the case between Photos 2 and 3, as Photo 3 shows a prominent tree shadow behind the thylacine while Photo 2 does not. This is discussed in the section on criticisms, below.

Identifying the animal

On first examination of Photos 2 and 3 the stripes have an odd appearance. One of the criticisms of the photos is that the stripes do not match a thylacine. The first impression given to this author (many years ago) was that the stripes are too broad and travel too far down the body (at that broad width) to match a thylacine.

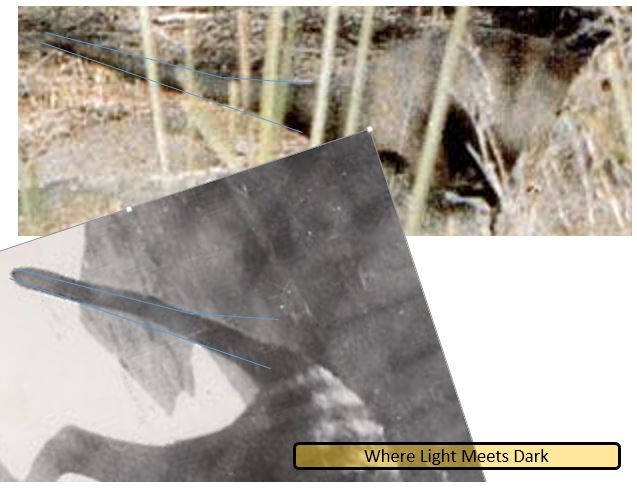

As a first step toward identifying the Cameron animal, a comparison is made between Photo 3 and a historical photograph of a young Tasmanian tiger.

Comparing stripes with a known thylacine

The following photograph shows a young Tasmanian tiger at Beumaris Zoo, Hobart.

Tasmanian tiger at Beaumaris Zoo. Source: Tasmanian Heritage and Archive Office (NS434/1/63).

The above photograph was chosen as the stripes on the animal's rump appear broad in comparison with the pale gaps between stripes. Further, the tail is clearly displayed. The first step in the analysis is to scale this photograph to match the Cameron photo.

In order to scale the photographs, a simple outline was made of the Cameron thylacine. This includes the straight line of the underside of the tail and two lines tracing the shape of the upper edge of the tail.

The zoo photograph was then rotated to approximately align the directions of the tails. An exact copy of the tracing was made and overlaid on the zoo image. The zoo image was then scaled and rotated as required to match tail length as closely as possible allowing for minor variation in the curvature of the two tails

This approach assumes that the length of a thylacine tail is relatively constant, with respect to the thickness of the stripes on the rump.

Scaling a known thylacine photo to match the Cameron thylacine Photo 3.

Having scaled the tail of the zoo animal to match the Cameron thylacine, the next step is to rotate the zoo photograph to align the rumps of the two animals.

Aligning the rump of a known thylacine with the Cameron thylacine Photo 3.

In the composite image above, the zoo photograph has had a transparency applied. The outline of the zoo animal is easily discerned. The outline of the Cameron thylacine tail is easily discerned and roughly outlined in blue. The outline of the Cameron thylacine rump is visible but not easily discerned. The composite image below traces the two back lines for ease of reference.

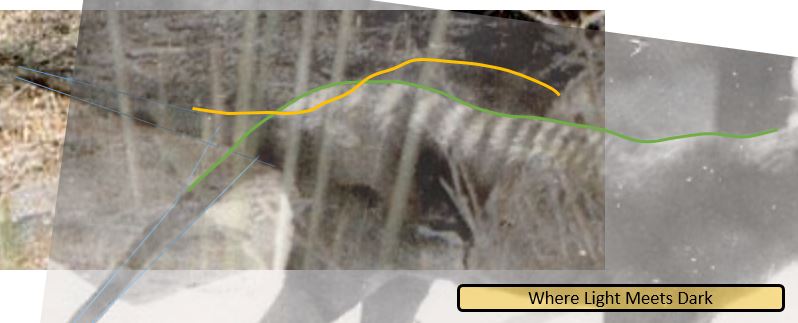

Composite showing relative positions of rumps (traced; green = zoo photo; orange = Cameron thylacine Photo 3).

The key question being examined is whether the apparently odd stripes may be a match for a thylacine. To this end, the final step in the analysis is to compare the stripes between the known zoo animal and the Cameron thylacine now that the two images have been scaled and aligned as best as possible given the slightly different postures in the animals.

In the composite image below a blue dot was placed at the point at which the Cameron thylacine becomes obscured from view. An orange dot was then placed on each stripe posterior to this point.

Composite showing the scaled, aligned photographs and counting stripes - blue dot is point at which the Cameron thylacine is obscured from view. Each orange dot counts one stripe.

Along the scaled matching section of rump, the zoo animal shows 8 stripes; the Cameron thylacine shows 7 stripes. Thylacines have a variable number of stripes along their backs, but this comparison shows that

- accounting for scale, the number of stripes visible on the Cameron thylacine is well within the range expected for the species.

Further, while on first inspection is appears the Cameron thylacine's stripes are broader than expected,

- once it is understood that we are seeing only the upper half of the rear half of the animal, the thickness of the stripes is comparable to that of a known thylacine example.

To illustrate this last point further, the composite image below overlays the Cameron thylacine Photo 3 on the zoo animal without using transparency.

Composite image showing Kevin Cameron thylacine overlaid on a zoo thylacine

The above composite gives a much clearer picture of how the Cameron thylacine's rump and stripes do match a verified thylacine example. The key insight into this understanding is that the Cameron thylacine photos do not show the rear half of the animal. Rather, they show the upper rear quarter.

The question that follows is that if we are only seeing the upper quarter of the animal, is there enough vertical room behind the tree's stump for the animal to have its legs present? That is, in the Cameron photo there is a tree root running along the ground obscuring the animal's feet from view. This root does not appear tall enough for there to be enough height behind the root to fit and obscure the animal's legs, if it is a thylacine.

To address this question we will consider the backstory to Cameron's photos.

Evaluating the back story

The New Scientist article explains how Kevin was able to approach and photograph this thylacine:

"The [photographs] were taken at intervals as Kevin approached, the last being from only metres away. The thylacine was busily digging at the base of a tree, its head down behind the stump, and it was only because it was so engrossed that Kevin could get as close as he did."

The key here is the claim that the animal was digging. In discussing the photos with the author, Cameron added that it was also eating and that the ground was damp (pers comm 1 Mar 2018).

That the animal was digging

If we look closely at Photos 2 and 3 a mound of dirt is visible behind the animal.

Cameron thylacine photos showing mound of dirt behind the animal.

In Photo 2 the shadow of the animal's tail is seen to fall over this rise, and behind it, defining its shape.

The presence of this mound of dirt supports the back story claim that the animal was digging.

The question remains whether there is enough room behind the tree root to hide its legs if the portion of the animal we are seeing is only the upper half of its rump.

The image below overlays a still frame, reversed, from film footage of a captive thylacine. In the film footage, zoo keeper Arthur Reid, off screen, is coaxing the thylacine into activity. At one point the animal crouches down as seen in this frame. Presuming that a digging thylacine might adopt a comparable pose, we can extrapolate the apparent slope of the dirt mound and check whether the legs rest above this line.

Comparing Cameron thylacine Photo 3 with a still frame from historical footage. Footage source: Thylacine Museum (film 4).

It can be seen the thylacine's legs do not terminate above the extrapolated slope of the dirt mound.

Before drawing any conclusion that the Cameron animal is not a thylacine, some caveats ought be noted. First, the zoo animal is not crouching as low as feasibly possible. Second, we cannot know how the other side of the tree root appeared. That is, there may be a depression in which the animal was standing (or crouching). Third, making this direct comparison assumes we have scaled the zoo animal here correctly.

- It would appear the Cameron thylacine's legs should not fit behind the tree root, but this cannot be proved without knowing the terrain behind the root.

- In summary, the mound of dirt supports the back story that the animal was digging.

That the photos were taken at intervals as Kevin approached the animal

A second element of the back story is that the photographs were taken in a sequence as Kevin approached the animal.

The composite image below shows the three photos scaled to match each other.

Comparing perspectives for the 3 Cameron photos.

Key elements have been highlighted in each image:

- Blue line = branch lying in foreground

- Orange oval = thylacine

- Red triangle = butt of tree trunk

- Green circle = clump of grass with shadow on it

The thin red lines serve to illustrate how some of these elements have moved with respect to another element between shots. This apparent movement is attributed to a change in perspective on the scene resulting from the movement of the photographer.

| Elements | Between photos | Change observed | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| The branch (blue line) with respect to the top of the thylacine's back (orange oval). | Between Photos 1 and 2. | The vertical distance has increased. | The camera was higher up while taking Photo 2. |

| ditto. | ditto. | The branch, which is in the foreground, has moved toward the right, with respect to the thylacine's back. | The camera moved to the left in order to take Photo 2. |

| ditto. | Between Photos 2 and 3. | The branch is out of frame. | The camera was closer to the thylacine, and viewed the thylacine from a higher perspective, and the branch disappeared off bottom of frame. (The increase in size of the grass clump bears out that the camera was closer; the comparison between the grass clump and thylacine, below, bears out the camera was higher). |

| The top of the thylacine's back (orange oval) and the clump of grass (green circle). | Between Photos 2 and 3. | The grass, which is in the background, has moved from left of the thylacine, to right of the thylacine. | The camera moved to the right in order to take Photo 3. |

| ditto. | ditto. | The grass has moved up. | The camera has moved closer and/or higher to take Photo 3. |

The final interpretation of events is:

- Photo 1 is taken with the camera low to the ground - as if the photographer is crawling. Grass blades can be seen obscuring the view, eminating from bottom-right of frame.

- The photographer moves to the left (possibly to come out from behind the grass) and a little higher/closer (possibly to get a better view, risking discovery now that at least one photo is taken) and Photo 2 is taken.

- The photographer then moves to the right (possibly to utilise the tree trunk as cover in order to get closer to the animal) and considerably closer/higher and Photo 3 is taken.

The above interpretation assumes Photos 1, 2 and 3 were taken in that order and that the focal length of the camera was fixed between shots.

In summary,

- The changes in perspective between shots is consistent with the back story that the photographs were taken at intervals as Cameron approached the animal.

- More-so, the evidence suggests the first photo was taken lying low to the ground, the second taken after moving out from behind cover, for a clearer view, and the third taken after taking advantage of the tree to allow Cameron to approach closer still.

Addressing the criticisms

A number of criticisms were raised against these photos in the weeks following their publication.

Shadows

In a letter to the New Scientist editor, Matt Webster wrote "My attention was drawn to the distinct shadow of the tree across the clump of grass in the background of the lower picture [Photo 3]. The upper picture [Photo 2] shows this shadow some way to the left of the clump, indication that this picture was shot at a different time" (15 May 1986, p76).

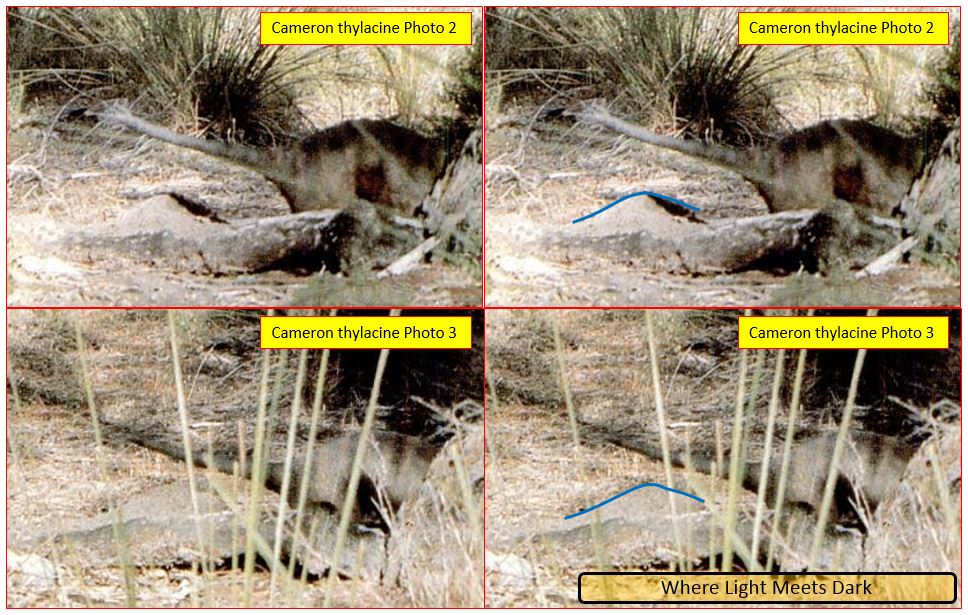

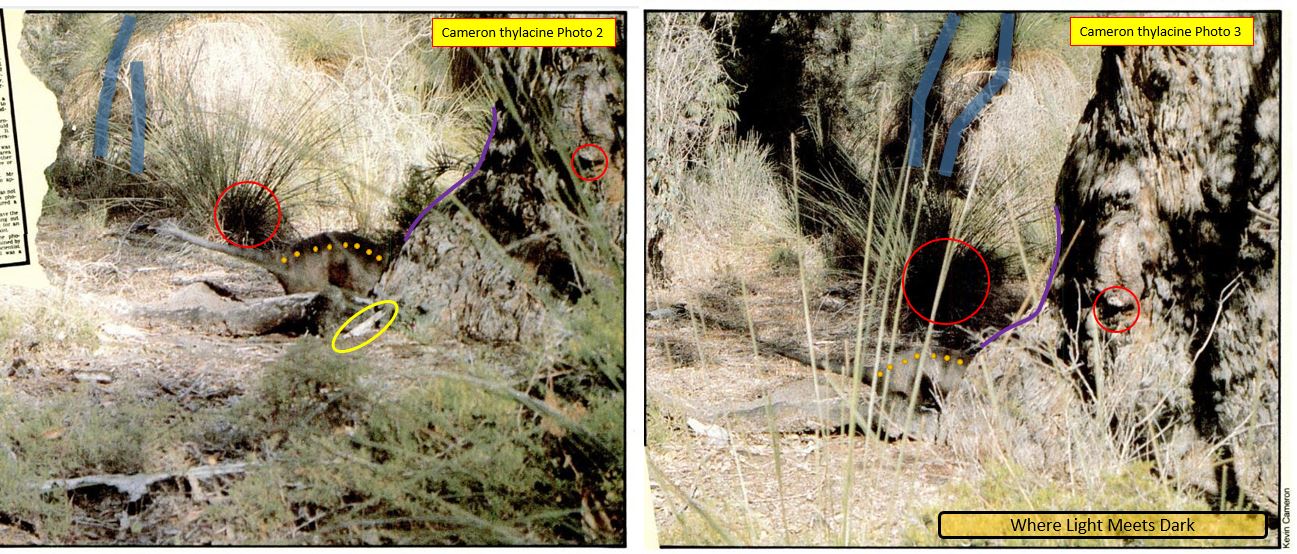

In the composite image below we take a look at this shadow and a few other features as they appear in Photos 2 and 3.

Comparing Photos 2 and 3 with particular attention on the tree shadow.

The larger red circle in each image shows where the tree shadow crosses over the clump of grass. Two blue lines trace vertical shadows being cast by the tree. Note that in Photo 3 the blue lines appear above the grass while in Photo 2 they are off to the left. Webster presumed this discrepancy to be due to the passage of time but this is consistent with the photographer changing his position between shots as was described above. As a further reference, the purple line traces the edge of the tree - this tree edge is very close to the circled clump of grass in Photo 3 (at right), but considerably distant from the same grass in Photo 2. Needless to say, neither the tree nor the grass moved between shots - it was the photographer who moved, and the tree's shadow moved across the frame in the same way.

This understanding was noted by L. M. Newell in a subsequent letter to the editor: "I now believe that the apparent movement of the shadow of the tree can be explained by the movement of the observer (to the right), and not the sun" (29 May 1986, p63).

Photo 3 also seems to have been taken from a higher perspective than Photo 2.

The dots on the thylacine's back mark stripes - eight in Photo 2 and seven in Photo 3. As expected, as the photographer moved to his right, the tree began obscuring the view of the thylacine.

The smaller red circle in each image shows a notable shadow on the trunk. Notice that the distance of this feature from the tree's edge (purple line) also changes between shots. Again, this is explained by the photographer moving.

The yellow oval in Photo 2 illustrates some object or feature that appears absent from Photo 3. The apparent disappearance of this object between frames is not easily explained. If the object is related to a very near foreground item - such as the grass blades passing through Photo 2, then its absence is understandable. The object does appear to rest against the tree root however, and if it does, its absence in Photo 3 is not explained.

Finally, the visual contrast of the shadow appears to change between shots. This may be attributable to passing clouds diffusing the light in Photo 2 and brighter sunlight casting the darker shadows in Photo 3.

- The apparent change in position of the shadows is explained by movement of the photographer rather than passage of time.

- There is one element in Photo 2 which is apparently absent in Photo 3 and there is no obvious explanation for this.

Rifle

Photo 1 is said to show the thylacine near centre of frame and was taken before Photos 2 and 3. The discarded rifle is noted in the foreground. On first consideration, this appears odd - it would seem the photographer has placed the rifle in front of himself in order to take the photograph.

Bob Ralph and Hilary Fry pose the question well in a letter to the editor - "We find it curious that the discarded rifle should be visible in this picture. There is no information on the focal length of the lens used but we find it difficult to imagine anyone laying down a rifle to take a picture of a distant animal and managing to include that rifle in quite sharp focus. Did Kevin Cameron, the tracker who took the photographs, lay down his gun and then step back the two or three paces needed to include it?"

In light of the discussion on the changes in perspectives between photos, above, it would seem that Photo 1 was captured while lying low to the ground. This author agrees that it seems odd the rifle was placed in front of the photographer but does not agree with Ralph and Fry that the physics of photography should have excluded it from view, especially in light of the understanding that the Photo was probably taken while lying low to ground. Having sought to photograph flighty wildlife on many occasions, this author speculates it is conceivable that once the thylacine was sighted, Cameron's eyes might never have left the animal. Lowering the rifle may have been done without directly viewing where it would lie.

- The visibility of the rifle in Photo 1 does not conclusively show either way whether or not the photo was taken of a live and alert animal.

Rigor mortis or unchanging posture

Cameron Campbell, curator of the online Thylacine Museum, discusses a follow-up article, written in 1990 by the same New Scientist author, Athol Douglas. Campbell states "Douglas concluded that apart from the first exposure, the thylacine in the photographs was a dead animal, rigid from rigor mortis".

Ralph and Fry in their letter to the editor do not speculate on the animal being dead, but do note the lack of change in the animal's posture:

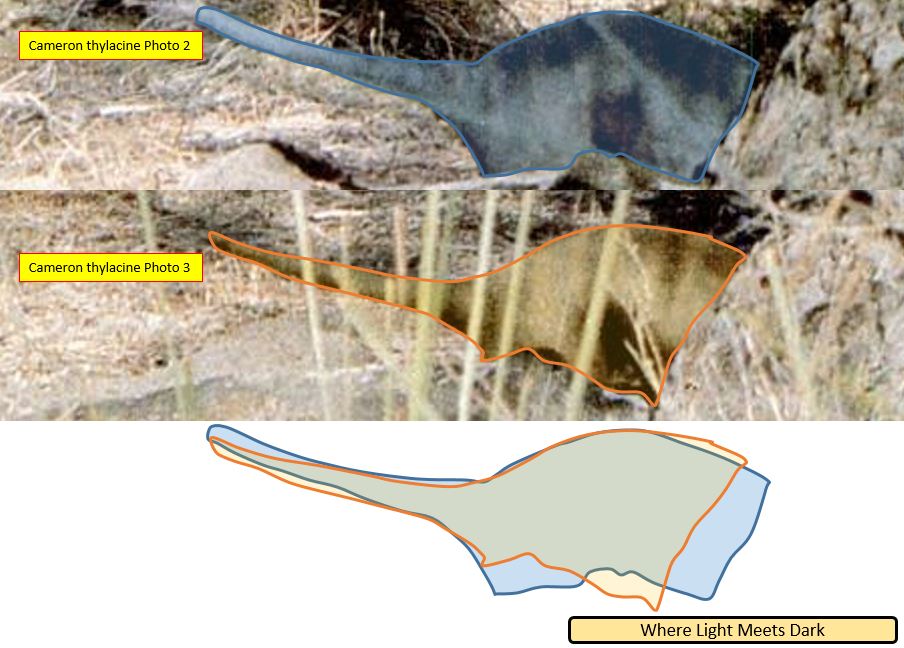

"The two photographs that show the animal more clearly [Photos 2 and 3] look as though they were taken from positions about three or four metres apart. How long would it take to move that much more closer? Given that a great deal of care would have been taken, let's say that it took 5 seconds, probably more like 10. How extraordinary that, in that time, a busily digging animal hasn't changed its posture, the curve of its back, or the angle of its tail, by the slightest amount. A cutout of the shape of the animal in the bottom photograph [Photo 3] can be superimposed exactly on the shape of the animal in the upper picture [Photo 2], and vice versa" (29 May 1086, p63).

The following composite image traces the animal's body in each of Photos 2 and 3, then overlays the tracings for comparison.

Tracing Cameron's thylacine for comparison of posture between shots.

Ralph and Fry's question is a fair one. Given the time it would have taken for the photographer to move from the position at which Photo 2 was taken, to that of Photo 3, the animal holds a near-identical pose between the two shots (even in spite of the change in perspective). The truth is that we do not know what a thylacine might do if it was digging. However one additional detail can be noted - the shadow being cast in Photo 2 by the tail onto the mound of dirt is not seen in Photo 3. The mound itself is visible so if the shadow were there, it should be visible. Photo 3 is the image in which the shadows of the trees exhibit the greatest contrast, so in all probability any shadow cast by the tail should exhibit clear contrast against the dirt mound. One explanation for the absence of this shadow is that the thylacine has shifted position slightly and the tail's shadow is falling behind the dirt mound, especially given the earlier conclusion that the tree shadows do not demonstrate a significant passage of time.

Similarly, the animal's back, in Photo 2, appears to have a shadow cast onto it. Note that this shadow does not extend onto the tail in that photo. Hence it appears the tree is casting a shadow onto the animal's back but its tail extends into the sunlight, thus casting its own shadow onto the dirt mound. In Photo 3 there is no such shadow on the animal's back and again one likely explanation is that the animal has moved. Given the additional information supplied by Cameron in speaking with this author that the animal was eating, it becomes more feasible that its hindquarters may move very little.

There is historical film footage of a thylacine eating at London Zoo in 1930. The clip, which can be seen at the online Thylacine Museum (film 6), shows the animal standing with a forefoot holding down a bone of meat as it chews at the bone. The first few seconds of this clip show the whole animal. While it is true its hindquarters move, they do not exhibit any great change to posture - certainly if two photographs were taken some seconds apart, the arc of its spine would be as similar between shots as is seen in the Cameron photos.

One final question is whether rigor mortis can lead to the tail being held so erect. One historical photograph that comes to mind showing a freshly killed thylacine with an erect tail is that depicting Alb Quarrell with his kill of 1928.

Alb Quarrell with a freshly killed thylacine, 1928. Source: The Conversation citing Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

In the full version of the photograph it can be seen the tail is being held aloft. This is not a rigorous analysis of whether a freshly dead animal in rigor mortis could exhibit a raised tail but clearly the pose may be held by a live animal.

- Changes in the shadow cast by the animal's tail, and in the shadow on the animal's back, suggest the subject of Photos 2 and 3 is not a completely inanimate object.

- Earlier analysis (in this article) suggests the shadows have not moved due to the passage of time.

- Historical footage of a thylacine eating suggest that basic posture of the hindquarters may remain relatively consistent for a period of time.

- It is plausible that the animal in Cameron's photos is a live animal in spite of its relatively consistent posture.

Stripes do not extend down leg

Campbell makes an additional note about the animal's stripes saying "the tail ... with its broad base, is certainly thylacine in appearance. The animal's stripe pattern, however, is atypical of what one would normally expect to see for the species, with the banding appearing broad and diffuse, and with no discernible extension of the stripes down the rear leg."

Given the interpretation above that we are seeing only the upper half of the rear half of the animal, a comparison is made between Cameron's photos and two historical thylacine photographs.

Composite image comparing Cameron thylacine Photo 3 with two historical photos. Both historical photos: Zoological Society of London.

In both the above historical photographs the stripes cannot be seen extending onto the rear leg, with the exception of two stripes in the upper image. In some ways the black and white historical images are of better quality - in being higher resolution, higher contrast (in the upper image) and unobscured. Yet despite this, the stripes cannot be seen clearly on the rear leg. In this author's opinion, the absence of stripes descending down the body of the Cameron thylacine is within reasonable expectation given the resolution, low contrast and general quality of the photographs and given the examples in historical photographs.

- The apparent lack of stripes does not exclude the possibility that this is a thylacine.

- The lack of stripes may be attributed to limitation of the photographic equipment.

Edited negatives

Douglas made the additional comment "when I saw the negatives, I realised that Cameron's account with regard to the photographs was inaccurate. The film had been cut [and] frames were missing".

It is impossible to verify these comments without first-hand access to the negatives, or photographs of them. Even then, taking Douglas' observations as accurate, it is still impossible to deduce the reason for which the negatives might have been cut and frames removed.

- The claim of edited negatives cannot be evaluated without viewing them.

Cameron's silence

Following the criticisms published against the photographs, it is generally accepted Cameron went silent on discussing these photos. Indeed it had been many years since he had spoken to anyone about them when he spoke with the author.

The reason for this silence is essentially that public comment began to imply that he had shot a thylacine. Cameron has maintained from the outset that the animal was not shot. In conversation with this author he repeatedly expressed respect and admiration for the species and the importance of its conservation. Cameron expressed pride in his Aboriginal culture and his years of assisting authorities through his tracking skills on missing persons cases.

From the New Scientist article:

"... Mr Cameron now claims the State Government is deliberately blocking his pursuit of a thylacine in WA. Mr Cameron said last week he was hired by the Agriculture Protection Board about four years ago to track and kill an animal in the South-West of WA. His hunt brought him to within touching distance of a tiger and immediate fame last November. ... He said this week it was significant the WA habitat of the tiger ... was subject to mining leases. If the tiger's presence was established, a conservation order could be placed on the land, he said. 'The department are not convinced it is a Tasmanian Tiger, but they want to know where I saw it ... They even want me to capture or kill it, but they don't want me to tell anyone about it.' said Mr Cameron. 'Government authorities are afraid to speak out because they know what it is. I think they are afraid of the cost involved. If we proved the animal was a Tasmanian Tiger, it would cost the Government a fortune. Apart from re-writing history books, they would have to make the habitat a reserve, stop ... mining in the area and declare the animal an endangered species.' Mr Cameron said the Agriculture Protection Board originally told him to prove an animal existed. The whole affair was to be kept secret. 'I was given a powerful Magnum handgun by the department," he said. 'They wanted the animal dead or alive.'"

After discussing the discovery of a dismembered kangaroo, the article continues "... Mr Cameron said he returned to the area and finally managed to get so close to the hunted animal he could 'look it in the eye'. 'It was a thylacine,' he said. 'I could have reached out and touched him. But I wasn't going to shoot him. If this was a Tasmanian Tiger I wanted to save it.'"

Conclusion

This article presents a thorough analysis of three of the five photographs taken by Kevin Cameron in November 1984, purportedly showing a thylacine in Western Australia.

Key conclusions drawn throughout the article regarding the identity of the animal are as follows.

- When it is understood that we are seeing only the upper half of the rear half of the animal, it can be seen that the animal's shape is consistent with a thylacine.

- Further, given the above understanding, the animal's stripes - which at first appear too broad for a thylacine - are consistent with a thylacine.

- Further, the fact that the stripes cannot be seen descending down the leg of the animal does not preclude thylacine; rather, historical photographs can exhibit the same appearance.

- In brief, the body shape, tail and stripes are all consistent with a thylacine.

Regarding the back story as recounted by Cameron, the key conclusions are below.

- A mound of dirt behind the animal supports the claim that the animal was digging.

- An evaluation of the changing perspectives between shots supports the claim that Cameron took the photographs whilst slowly moving closer to the animal.

Regarding key criticisms of the photographs, conclusions are below.

- The apparent shift in the shadows cast by trees can be attributed to the photographer's change in perspective between shots; they do not indicate a passage of time.

- The presence of the rifle in the first photo has no bearing on whether or not the photographs are authentic.

- Regarding the apparent lack of change in posture by the animal there is tentative evidence to suggest that in fact the animal has moved between shots, albeit slightly; and examination of historical film footage of a thylacine eating shows that general posture may be held for a period of some seconds while the animal is so engaged. (In personal communication Cameron noted that the animal he photographed was digging and eating).

As a result:

- The claim that the Cameron photographs show a living thylacine remains plausible.

There are some items of consideration that have not been explained. These include:

- One object visible in Photo 2 is absent in Photo 3 and there is no obvious reason for why this is so.

- In a subsequent article, Athol Douglas made the claim that the negatives had been cut and some frames removed from the set. The reason for this is not known and may or may not have a bearing on the above conclusions.

- If we are only seeing the upper half of the rear half of the animal, there does not appear to be enough room behind the tree root to have the animal's full legs - but this cannot be certain without knowing the terrain behind the root.

The author welcomes feedback and alternative interpretations on this article.

Revisions

- 4 Mar 2018 - add conclusion note about legs fitting behind the tree root.