Rehberg Bagshaw audio recordings analysis

In brief...

- 9 audio recordings made

- 10 audio recordings analysed

- Opinions are divided between sugar glider, owl and Tasmanian tiger

- Add your thoughts to the discussion at the bottom of this page

- Mini documentary filmed during the exepdition - watch below

- Rob and Chris will carry on their searches separately moving forward, and you can help either or both of them via the links below.

Mini Documentary - 20 minutes

| All 9 audio recordings - 8 minutes

Take care if listening to this audio using headphones - the volume of the recordings has been increased as the animal call is faint. However some recordings contain foreground noise which will be very loud, especially if played through headphones. |

Overview

Background

In February 2017 Chris Rehberg (this author) and Rob Bagshaw (owner of the YouTube channel in his name) teamed up for an expedition in search of the thylacine.

Previously, as documented here, Chris had conducted numerous searches in Tasmania and Rob even more. While Chris has focused on hiking to remote locations, Robert has taken the luxury of a helicopter to drop him into even more remote locations.

In 2013 Chris heard brief vocalisations in a sequence of "tiu-tiu ... tiu-tiu ... tiu-tiu ... tiu" at a distance across a valley. This experience determined the destination chosen for the 2017 expedition.

Vocalisations

During the 2017 expedition multiple series of animal vocalisations were heard that fit descriptions of the Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus, or thylacine). Each series of calls is termed an "event". Seven separate events took place over the course of approximately two hours during one night and is likely to have involved two or three separate animals. Individual event durations ranged from a few seconds to in excess of four minutes. Audio recordings were made by both Chris and Rob of portions of multiple events and subsequent to the trip these have become a focus of investigation.

A comparison with 54 species of Tasmanian bird audio recordings published at xeno-canto yielded no match with the recorded calls.

A variety of experts has been consulted for opinions on the call. Three candidate species are proposed:

- Sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps)

- Boobook owl (Ninox novaeseelandiae) (or bird, more generally)

- Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus)

Three persons with extensive audio recording experience for native wildlife and/or nocturnal soundscapes on mainland Australia, have suggested the call originated with a sugar glider.

Three persons with extensive Tasmanian wildlife and wilderness experience, all dismissed sugar glider as an ID and said it was not a call they'd heard before. All suggested the call may possibly be from a bird.

One author on Australian owls has suggested the call originated with a sugar glider.

There are no known audio recordings of the Tasmanian tiger and there is no person today who can unequivocally say they know they have heard a thylacine (ie. saw the animal as it vocalised). Therefore based on historical written descriptions of the Tasmanian tiger having a "yipping" call, the thylacine remains a candidate.

Identification

There are mixed conclusions regarding identification of the animal call.

Chris concludes a boobook owl was almost certainly present, based on: very soft vocalisations recorded but not heard at the time; wingbeats heard overhead on two occasions during otherwise silent periods in between yipping calls; and a notable bird call occurring 3 minutes after the yipping calls finally ceased, later matched to audio recordings of boobook owls. However determining whether the yipping call originated with one or more boobook owls and/or gliders is problematic for the following reasons: many of the soft bird-like sounds that appear in the recordings do not appear to affect the timing of the yipping calls - suggesting different animals making the different calls (though prospectively two different owls); Rob heard twigs snapping underfoot as the first yips began (not easily explained by either owls or gliders); and one event seemed to involve a call being heard across a valley - a distance well in excess of 1km, which is problematic for either a glider or owl suggestion. This distant call was qualitatively different, matched Chris' experience from 2013 and also contained paired vocalisations which matches descriptions of hunting thylacines. For this distant call Chris believes that thylacine remains the strongest candidate. While spectrogram analysis suggests a match with glider, this is not definitive, as different animals can produce similar spectrograms. For the nearby calls, Chris believes an owl is a more likely candidate than sugar glider, if it is not thylacine. Given there appears to be two animals involved in both the present recordings and the independent recording analysed, this call may be related to interaction between two animals, such as courtship.

Robert believes the sound came from an animal on the ground and that it matches the description of thylacine. He feels that the recorded sound doesn't match the sound as it was heard during the events and believes the sound came from an animal much larger than a glider. Rob believes the call is worth further investigation via the deployment of Song Meter audio recording devices and camera traps.

Notable observations

| Observations | Glider explanation | Owl explanation | Tiger explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event B was heard at a distance estimated 1 to 3km | For this to be a glider, Chris and Rob may have both misjudged distance. This could be the case if the glider is facing away from the listeners and/or positioned on the far side of a tree trunk. | Same as for glider. | Pre 1936 reports suggest tigers could be heard at a distance of 1 to 3km |

| Calls near the camp originated from essentially opposite sides of the camp (and perhaps other points as well) | For this to be a glider, it is unlikely a single glider moved to multiple points; it is more likely multiple gliders were involved. However, if multiple gliders were involved then they did not call over the top of each other. Rather, one called for 4 minutes, there was a pause of several minutes, then another called for several minutes from another location. Finally, there was another pause and the calling returned to the first location. It is unknown whether this is likely glider behaviour in the wild. | Same as for glider. Alternatively, a single bird flew between points - and it is noted that wingbeats were heard between events. | If a single tiger was involved, it would have the capacity to move around the campsite. However in doing so it must have trod completely silently with no sounds of breaking twigs or similar being heard except for the first cracking of twigs immediately prior to the first calls. |

| Calls on opposite sides of the camp had different pitch. | This could be due to two different animals. This could also be due to localised topography affecting acoustics. It seems more likely that two different animals were involved - this was the impression given to both Rob and Chris. | Same as for glider. | Same as for glider. |

| Four persons have suggested glider; Three persons have suggested a bird | Spectrograms and timing of word parts correlate with glider. However, different animals are able to produce similar spectrograms, so this is not definitive evidence. To some experts the call sounds like glider; yet to others it specifically does not sound like a glider. | Other sounds in the recording sound avian. A call readily attributable to an owl was heard within minutes after the last yipping calls. However even those with extensive owl experience say they have never heard this call. | Nobody alive today can unequivocally claim to have heard a tiger. Some written accounts describe the tiger's call as a "yip", matching the descriptions by Chris and Rob. However the "yip" call is often described as occurring in pairs and occurring very briefly. All events except the distant one had the yip calls as single vocalisations and many of the events lasted minutes. |

Table of notable observations and implications for identification.

Introduction

There is no known existing audio recording of the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus). The last known captive specimen died at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart on the night of 7 September 1936. In 1986 the species was declared extinct. Since 1936 ample sightings and encounters with the species have been claimed but without sufficient evidence to alter the accepted extinction date in 1936. In February 2017 Chris Rehberg (author) and Rob Bagshaw were conducting a search for the species in Tasmania when animal vocalisations were heard that match written descriptions for the thylacine. Portions of these vocalisations were recorded.

Context

Commencing 2008 Chris has conducted a series of informal searches for the species in Tasmania. In June 2013 an animal vocalisation was heard from a distance that matched written descriptions for the species. During that encounter Chris had spent a day deploying camera traps along a mountain range in the southwestern quarter of Tasmania. Returning to his tent, he was leaning against an embankment, eating, when a call was heard from across the valley. The nature of each vocalization was described at the time as being distinct pairings of "tiu tiu" or "tew tew". The full sequence of vocalisations had seven word parts in three pairs, followed by a single vocalisation: “tiu, tiu … tiu, tiu … tiu, tiu … tiu”. An attempt was made to record this call but the call was brief and ended before recording could commence. A photograph of the scene was taken, together with an indication of the direction of the call. This was later matched via satellite imagery of the campsite area in order to calculate bearing. Crossing the valley in this direction led to the end of another ridgeline and this became the target destination for the search that is the subject of this article.

Photo - a brief series of calls was heard at a distance in 2013. This photograph indicates the direction from which the call was heard.

In January 2017, Robert Bagshaw offered to meet up with Chris in Tasmania to provide transport and join him on a search that was scheduled to span a few days. Robert had also conducted several searches for the thylacine over the prior six years and had pre-existing plans to spend up to a month in Tasmania. Despite previously considering teaming up for a search, this was their first meeting. On 26 February, Chris flew to Launceston and Robert arrived at Devonport via ferry from Melbourne. The pair met near Deloraine then travelled to the vicinity of the target search area. On February 27 they hiked into the Tasmanian wilderness, deploying one camera en route to the target destination. After reaching the intended location – affectionately named “base camp” – Chris proceeded individually to ascend the ridge, deploying a further four cameras. Returning to base camp, preparations were made for nightfall.

In Hobart on this night, sunset was at 19:58, nautical twilight was at 21:02 and astronomical twilight was at 21:39.

Just before 21:00 Chris was kneeling on the ground, leaning into his tent organising camp items. Robert was standing nearby spotlighting for wildlife. At 21:00 Robert heard the first vocalisation and called “Shhh”. Chris paused, heard nothing and continued working in his tent at which point Robert again called “Shhh”. This second occasion Chris heard a call best described as “yip”. This was followed by a pause then one further “yip”. In total, Robert had heard the yip call three times; Chris two.

This was the first of seven separate series of calls made over the course of two hours. Three of the series consisted of fewer than 10 yips. Four series exceeded two minutes of continuous calling each. The longest series exceeded four minutes of continuous calling. Both parties estimated six of the calls as being in the vicinity of the camp and one call being considerably distant.

Summary of the calls

The first series consisted 3 yips as described above, near base camp. The second series consisted of 6 or 7 word parts at some distance. The word parts are described by Chris as “tiu” and match the sound of the vocalisations heard in 2013. The third series commenced one hour later and persisted several minutes in close proximity to base camp. The fourth series consisted 2 or 3 isolated yips. The fifth series commenced several minutes later, from the opposite side of base camp, was the longest series and lasted several minutes. The sixth series came a few minutes later, close to base camp. Its direction was indiscernible to Chris but Robert reported that together, the various series of calls came from a variety of points encircling the camp. The seventh and final series came a few minutes later, also lasted several minutes and the frequency of vocalisations per unit time during this series had decreased.

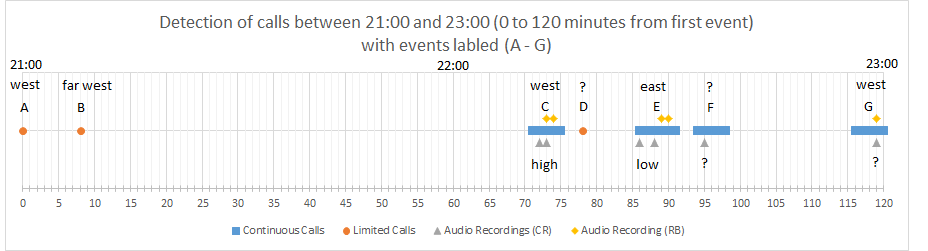

Table 1 lists each series of calls as vocalization events A through G.

Event | Start Time | Timeline | Duration (mins) | Yips | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A | 21:00 | 0:00 | <1 | 3 yips | breaking of twigs underfoot, followed by 3 yips, near camp, west |

B | 21:08 | 0:08 | <1 | 6-7 tius | 6 or 7 tiu calls, at considerable distance, include double-tiu call |

C | 22:11 | 1:11 | 4 | 4:00 yipping | 4 minutes of constant yipping, near camp, west |

D | 22:18 | 1:18 | <1 | 2-3 yips | 2 or 3 yips, near camp |

E | 22:26 | 1:26 | 6 | 6:00 yipping | continuous yipping, near camp, opposite side, lower tone |

F | 22:34 | 1:34 | 4 | 4:00 yipping | continuous yipping, near camp, direction unknown, higher tone |

G | 22:56 | 1:56 | 4 | 4:00 yipping | continuous yipping but isolated yips, spread out, near camp, west |

Journal of events

A journal of events was written in real time as events unfolded. Timing of events was noted using the time displayed on Chris’ phone. Event C is reported as commencing 22:11 and lasting 4 minutes; this means the first call from this series was heard sometime between 22:11:00 and 22:11:59 and the last call from this series was heard sometime between 22:15:00 and 22:15:59. The time-span for this series is therefore at least 3:01 and at most 4:59. The mean/median value of 4 minutes is reported.

Timeline of events in visual format

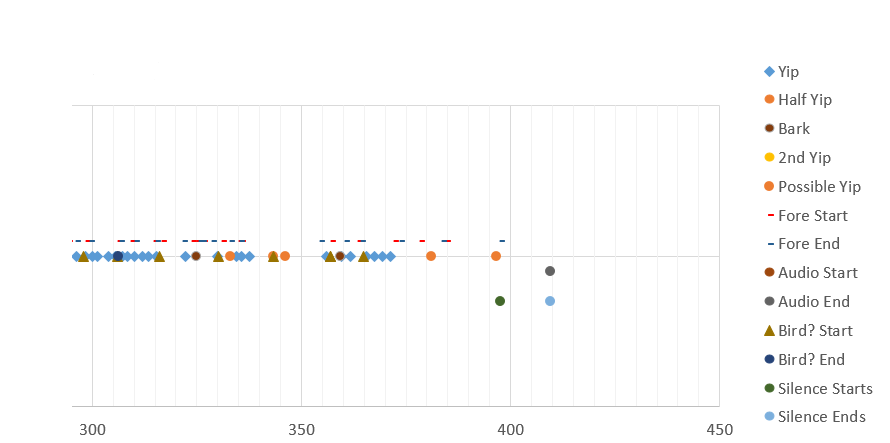

Figure 1 illustrates the timing of the vocalisation events heard. Each orange dot represents a minute of time during which some vocalisation was heard and blue bars span several minutes during which vocalisation was heard. Events A, B and D consisted fewer than 10 word parts each (3; 6-7; 2-3). Events C, E, F and G consisted of continuous calls of single yips for durations exceeding 3 minutes each. Direction of call is given where known ("west"; "far west"; "?"; "east") and pitch of call is indicated ("high"; "low"). The axis shows minutes from the first vocalisation (0) to the last (120).

Summary of audio recordings

Nine audio recordings totaling 7 minutes and 48 seconds of audio was recorded across 9 separate files using three different recording devices. Fifty-nine seconds of audio was recorded by both parties simultaneously, leaving 6 minutes and 49 seconds of actual time recorded.

Six audio recordings were made by Chris: two during event C; two during event E; one each during events F and G.

Three audio recordings were made by Robert: a two minute recording during event C; two subsequent recordings.

The most notable recordings occurred during events C and E.

Table 2 lists the audio recordings made.

Recording | Date | Start Time | Duration | Event | Recorder | Device | Animal Pitch | Definite Vocalisations | Possible Vocalisations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CR1 | 27/02/2017 | 22:12 | 1:12 | C | Chris | iPhone 6s | High | 50 | 2 | The final 41 seconds of CR1 overlaps the first 41 seconds of RB1. |

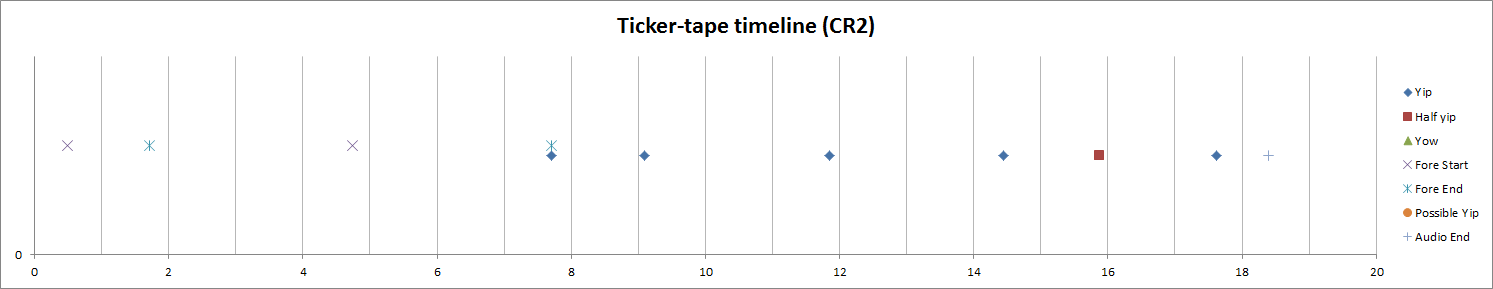

CR2 | 27/02/2017 | 22:13 | 0:18 | C | Chris | iPhone 6s | High | 6 | CR2 is fully contained within RB1. RB1 has zero foreground noise and captures more animal data than CR2. | |

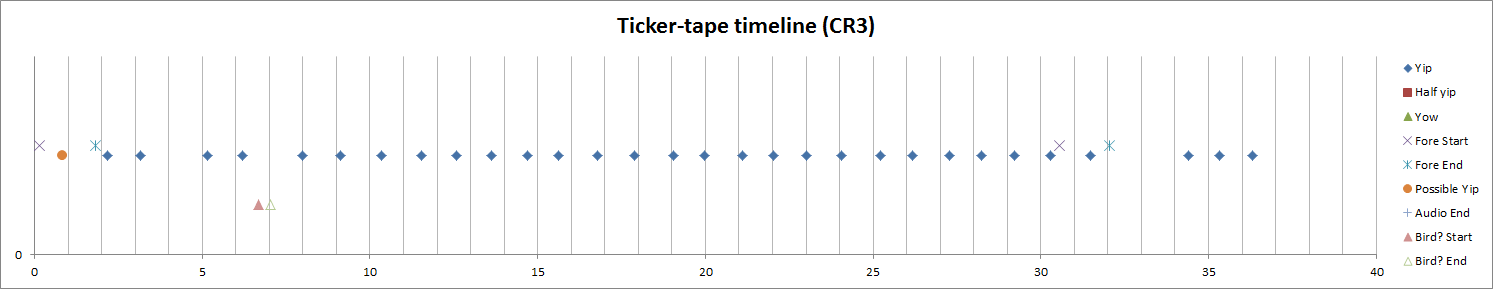

CR3 | 27/02/2017 | 22:26 | 0:37 | E | Chris | iPhone 6s | Low | 32 | 1 | |

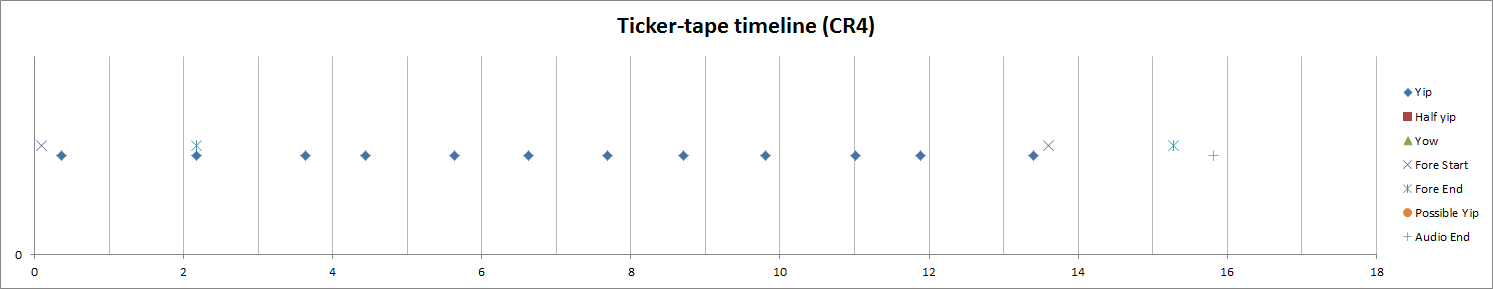

CR4 | 27/02/2017 | 22:28 | 0:16 | E | Chris | iPhone 6s | Low | 12 | ||

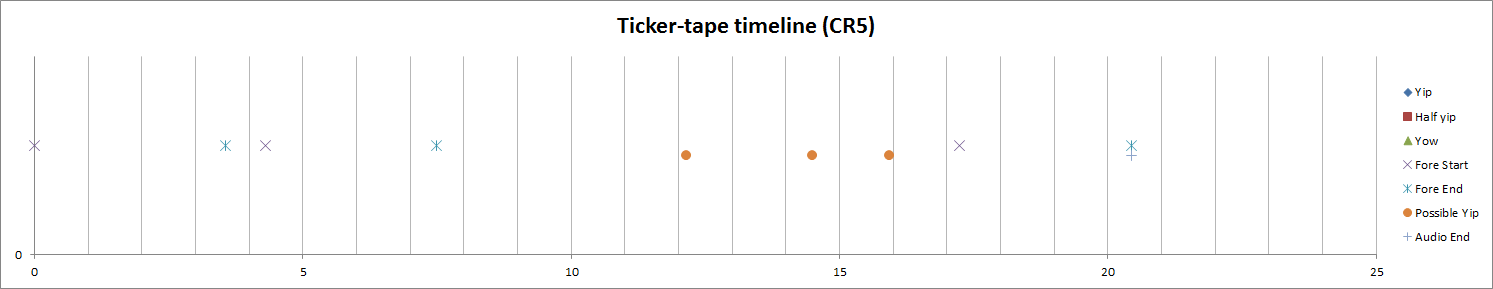

CR5 | 27/02/2017 | 22:35 | 0:21 | F | Chris | iPhone 6s | 3 | |||

CR6 | 27/02/2017 | 22:59 | 0:15 | G | Chris | iPhone 6s | 2 | |||

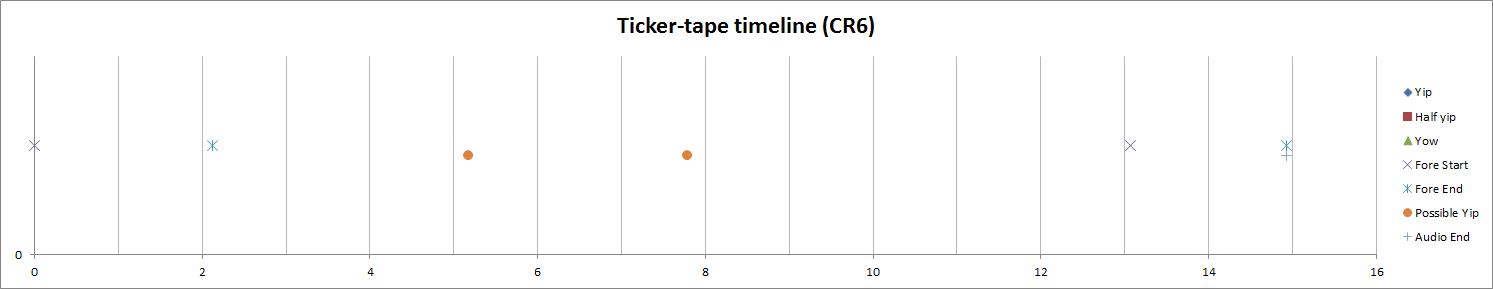

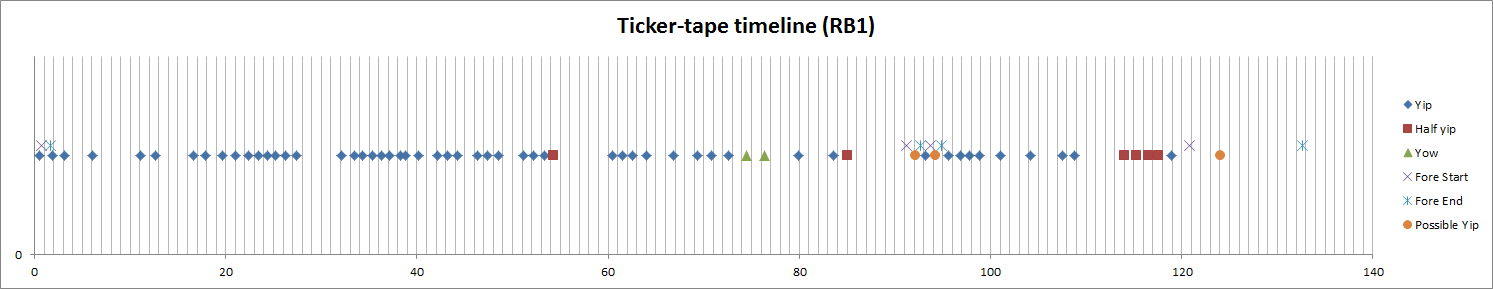

RB1 | 27/02/2017 | 22:12* | 2:13 | C | Rob | iPhone 5 | High | 62 | 3 | The first 41 seconds of RB1 overlaps the final 41 seconds of CR1. |

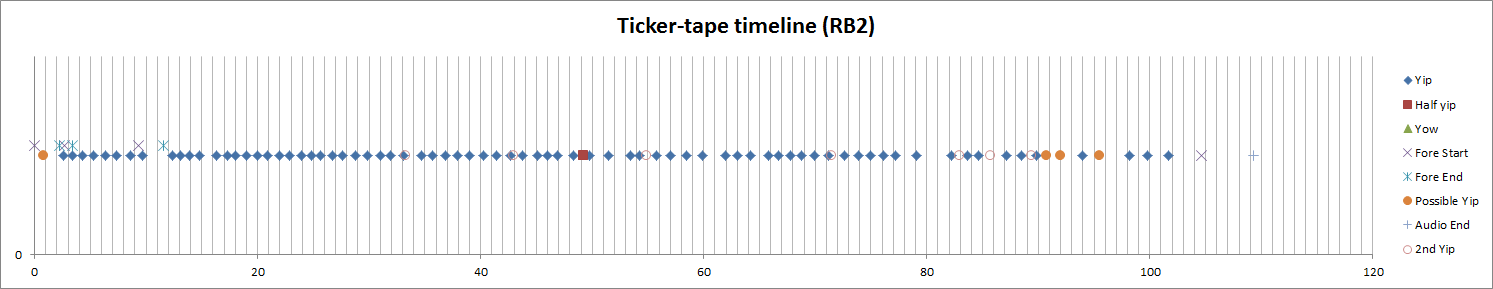

RB2 | 27/02/2017 | 21:34^ | 1:49 | E | Rob | Sony a7R | High and Low | 84 | 4 | |

RB3 | 27/02/2017 | 22:04^ | 0:47 | G | Rob | Sony a7R | 8 | 6 | Likely records the final 'yip' vocalisations heard for the night. |

Further recording attempts were made by Robert but none produced any usable material and these attempts are ignored for the purpose of this analysis.

All of Chris’ recordings were made with an iPhone 6s (model A1586) wearing an iFace Mall protective cover using the Voice Memo app. The first of Robert’s recordings was made with an iPhone 5 using the Voice Memo app. Robert’s subsequent recordings were made with a Sony a7R digital SLR camera using video mode.

The recording start times for CR1 – CR6 were obtained from the audio file after transfer to a Windows based PC via cable using CopyTrans (version 5.516). RB1 was transmitted via SMS then transferred to a Windows based PC via cable using CopyTrans (version 5.516). During this process the recording’s start time information was lost from the file. The start time for RB1 was deduced by ascertaining an overlap between RB1 and CR1 as determined by the timing of the animal calls. RB1 commences recording 31 seconds into the recording of CR1. As such, the RB1 start time is 31 seconds after the start time of CR1. The recording times for CR1 – CR6 did not present a seconds time component, therefore RB1 is deduced to have commenced either also during 22:12 – 22:13 (as indicated in Table 2) or between 22:13 and 22:14.

^The file timestamps for RB2 and RB3 show 21:34 and 22:04 respectively. This conflicts with the extensive journaling and a proposed explanation is that the Sony camera's timestamp was out by 1hr due to daylight saving configuration. Checking the camera clock on 6 April 2017 (after a change in daylight saving on 2 April) shows the camera's timestamp is correct (to within 5 minutes) - this implies that prior to 2 April, the camera was incorrect by 1 hour. During the check on 6 April it was noted the timestamp is 5 minutes faster than that provided by national mobile network provider Telstra which is also the mobile network used by Chris' iPhone. Therefore, to correlate the Sony recordings with the journalled events and timestamps from audio files recorded by Chris' phone, RB2, with a timestamp of 21:34, should be interpreted as having been recorded at 21:34 + 1 hour - 5 minutes = 22:34 - 5 minutes = 22:29. Similarly, RB3 was recorded at 22:59. This puts RB2 during event E and RB3 during event G based on the times of those events as journaled by Chris. Despite RB3 and CR6 both being recorded during the minute of 22:59, no overlap can be detected - CR6 contains only 2 possible yips separated by 2.615 seconds. No gap of approximately 2.6 seconds was found in RB3.

Additional files recorded by Rob on the Sony camera (00085; 00087; 00088) did not contain any calls.

Sequence of events

Following the 3 yips during event A, Chris came out of his tent and both parties shone torches in the direction of the call in an attempt to locate the calling animal. Nautical twilight had just transpired and the environment was notably dark compared to just a few minutes prior. They discussed the call, its perceived distance and direction. At 21:08 Robert indicated he could hear the call again. Chris indicated that he could not hear the call and Robert clarified that the direction differed and this call appeared to come from further away. Chris removed his beanie, which had been covering his ears and attempted to discern a more distant call. Three vocalisations were heard by Chris, described at the time as matching the “tiu” sound he had heard in 2013. The pattern of these latter 3 tius consisted a single tiu, followed by a pause, then two additional tius: "- tiu … tiu, tiu”. Robert reported at the time hearing 6 or 7 vocalisations.

Discussion was held concerning the two series of calls just heard and it was agreed that the latter series appeared to be a response, from a distance, to the first series. It was also agreed that the first three yips differed in nature from the second series. Chris used words such as “gentle” and “tentative” in his journal at the time to describe the first series, and “assertive” for the second series. Robert agreed with this distinction and both thought it feasible the first series may have come from a younger, less confident animal and that the second series may have come from an adult animal as a reassurance.

Chris estimated the first series to have come from 20 to 30m distant; Robert initially estimated 100 to 200m then revised this to 80 to 120m. Both estimated the second series to be across the valley and therefore approximately 3km distant based on map readings. This compares with calculations for the 2013 call which put the 2013 call at approximately 3.8km distant assuming that call came from across the same valley (along a different line of sight).

At 21:17 Rob went entered one tent. A few minutes later Chris entered a second tent and continued to journal details regarding events. The sound of a ringtail possum squeaking overhead could be heard occasionally, together with litter it was dropping nearby. By 22:07 Rob had apparently fallen asleep and there was a scratching sound outside Chris’ tent.

Just four minutes later, and 1 hour 3 minutes after the distant call (event B), at 22:11 the third series of yips commenced – and continued for four minutes. The direction and proximity for this event (C) matched that of event A: to the west and slightly uphill. The notes from Chris’ journal read “[Calling] again. Constant yip yip. Can't count. ... Maybe 20?? Squeaky again - it's the yip. Still going. 40? Singles. 10:15 stopped. About 4 minutes!”

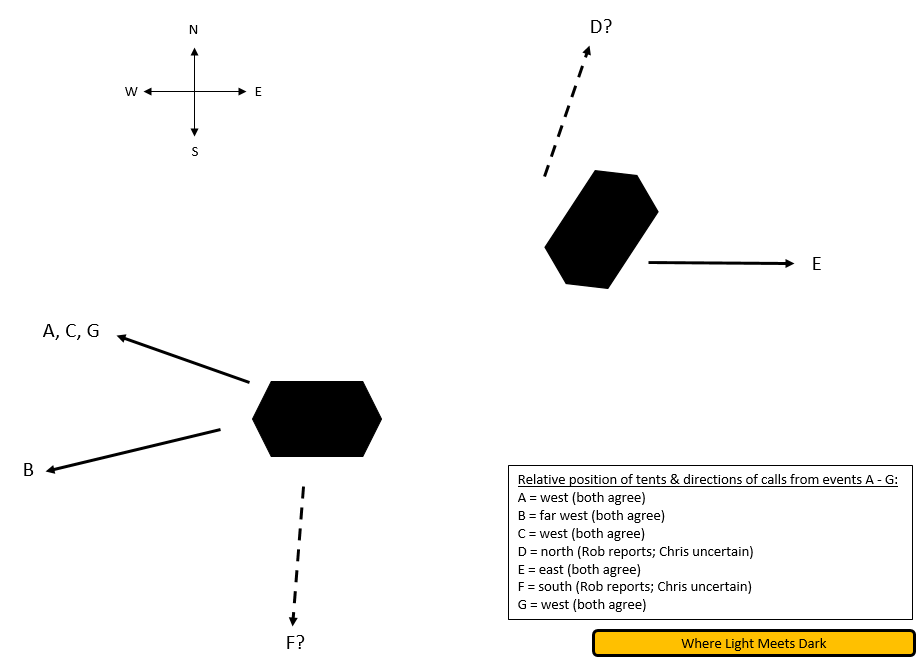

Illustration showing relative positions of tents and directions of calls for vocalisation events A - G. Direction of calls during events D & F are less certain than the others.

Both Chris and Rob took audio recordings during event C. At 22:18 Chris recorded “just two or three” more yips in his journal (event D) and the sound of wingbeats overhead. From one tent to the other, Robert asked “Did you record that too?” Chris replied “Yes”. Robert asked “What do you think that was?” Chris replied “Same thing” [as the first two events].

In the minutes that followed, Chris played back the recording to verify that the animal’s call could be heard. At 22:26 a series spanning five minutes began. These calls had a lower tone than event C. Robert questioned later whether this may have been a different animal but it may also be possible that the topography of the landscape was altering the sound’s quality. Chris noted this series of yips originated from the other side of base camp.

After a few minutes’ pause the call recommenced for another 4 minutes (event F). Chris recorded in his journal that he could not discern the direction.

Finally, At 22:56 wingbeats were again heard overhead and the calls recommenced (event G) but these were widely spaced apart even though the sequence lasted another 4 minutes. The origin for this series of calls was the same as for event C.

Robert later noted the animal appeared to him to call from four points around the camp with the final set of calls originating from the same location as the first set.

A camera trap had been positioned some 30 metres from the tents, toward the south, and facing the tents. Later inspection showed no animal captures after Chris and Robert entered their tents.

At 23:03 a bird call was heard, but not recorded, that was later interpreted as being from a boobook owl.

Mapping audio recordings to vocalisation events

Table 3 lists the audio recordings made, together with their time of creation, file name, duration and the vocalisation event recorded.

Recording | Date | Time | Title | Duration | Event | Recorder | Device |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CR1 | 27/02/2017 | 22:12 | Yipping | 1:12 | C | Chris | iPhone |

CR2 | 27/02/2017 | 22:13 | New Recording 34 Yip | 0:18 | C | Chris | iPhone |

CR3 | 27/02/2017 | 22:26 | New Recording 34 More Yips Opposite Dirextion | 0:37 | E | Chris | iPhone |

CR4 | 27/02/2017 | 22:28 | New Recording 34 - Third Location Yips Like… | 0:16 | E | Chris | iPhone |

CR5 | 27/02/2017 | 22:35 | New Recording 34 Fourh Animal But Nothing… | 0:21 | F | Chris | iPhone |

CR6 | 27/02/2017 | 22:59 | New Recording 34 More Yips At First Location… | 0:15 | G | Chris | iPhone |

RB1 | 27/02/2017 | 22:12 | New%20Recordingthacine.m4a | 2:13 | C | Rob | iPhone |

RB2 | 27/02/2017 | 22:29 | 00086 | 1:49 | F | Rob | Sony DSLR |

RB3 | 27/02/2017 | 22:59 | 00089 | 0:47 | G | Rob | Sony DSLR |

Further calls on subsequent nights

Two nights later, on the night of 1 March 2017, Chris returned to base camp alone in the hopes of hearing the call again and this time capturing photographic evidence of the caller. On the first night of calls, neither researcher attempted to leave their tent for fear of disturbing the caller. On this subsequent attempt there would be little more to gain by remaining silent if the caller called again. Unfortunately, apart from a small macropod vacating its den a little before 9pm (as it had two nights prior), there were no further vocalisations. A single camera trap had been deployed at base camp and this was checked but no images had been captured.

Robert, however, chose to camp at a separate location approximately 10km away. At various points of the night Robert mimicked the unknown call using his own voice. On two separate occasions he illicited replies matching those heard on the night of 27 February. Robert estimated the first reply to be within approximately 200m of his camp, while the second was quite distant and more than 1km away.

Earlier the same evening, Robert explored remote roadways by vehicle. At various points he mimicked the call and at one point a quadrupedal animal appeared on the road at some distance. He drove toward the animal which rounded a bend. Upon rounding the bend the animal was still present. A dashboard camera was running however this subsequently overwrote any recording from that night due to misconfiguration.

Finally, during our expedition, our recordings were played back to an independent thylacine researcher. This person, who is anonymous, encamped on the night of 6 March (8th day from when made our audio recordings) approximately 5km from Robert's campsite of 1 March. The researcher reported that at approximately 3am an identical call was heard which persisted for approximately 1 hour. It was estimated the animal was initially some distance off, approached to within 250 metres, then retreated in the direction it had come. Apart from this vocalisation only a single possum was heard, earlier in the night.

Table 4 lists the three separate nights on which vocalisations were heard. All audio recordings come from the first incident.

| Incident | Date (night of) | Day | Notes | Heard by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 Feb | 1 | On the night of this day, multiple calls heard by Rob and Chris over extended period; several recorded. | Chris and Rob |

| 2 | 1 Mar | 3 | On the night of this day, calls heard by Rob (after mimicking call) from two locations (approx 10 km from location of incident 1) - one near, 200m; other distant, >1km. A quadrupedal animal appeared on the roadway after mimicking the call. | Rob |

| 3 | 8 Mar | 8 | On the night of this day, calls heard by anonymous researcher (after earlier hearing Rob play back audio) (approx 5 km from location of incident 2) over period of 1 hour; first distant, then approaching to 250m, then retreating again. | Anon |

Analysis of the audio recordings

On conclusion of the expedition, a number of lines of enquiry were pursued in order to discover the identity of the caller in the audio recordings:

- Expert opinion was sought

- A database of audio recordings of Tasmanian birds was searched for a match

- The audio was repeatedly played back (yielding interesting details not noticed during the events)

- Spectrograms of the audio were produced and compared with spectrograms for sugar gliders and boobook owls

In analysing this set of events, a number of factors are considered:

- In which ways does an analysis of the audio support or contradict an identification of each of: sugar glider; boobook owl; and thylacine?

- Are there behavioural elements noted in the sequence of events that might implicate a species identification?

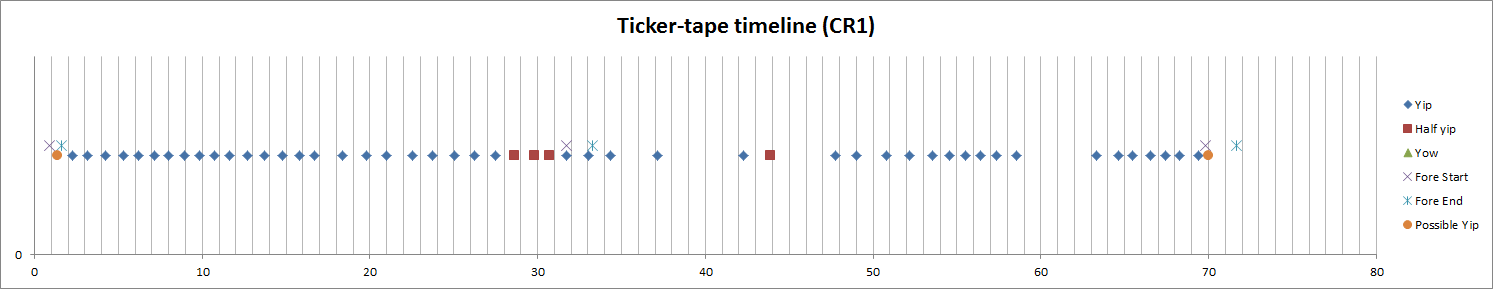

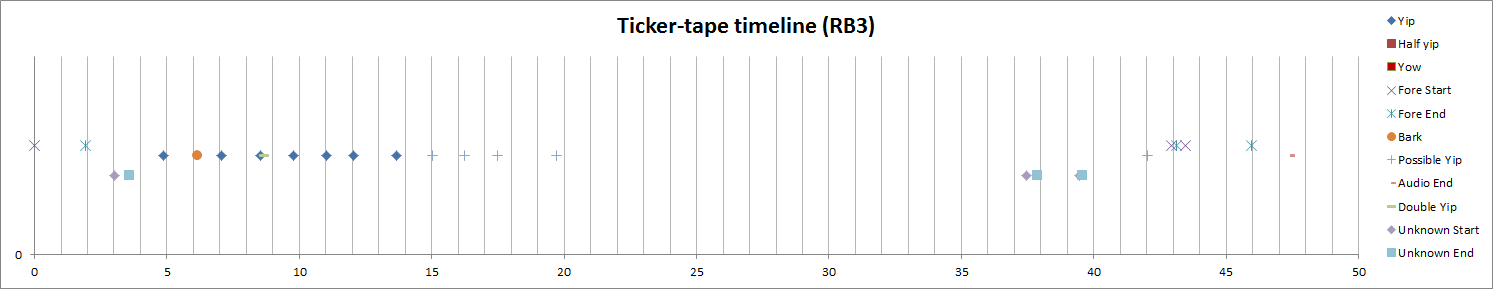

Proposing a visual documentation methodology for audio recordings - ticker-tape timelines

In order to visualise the timing and spacing of individual calls (and other audio sounds) that were recorded, a method is proposed for documenting audio file contents visually: the "ticker-tape timeline". A methodology for producing ticker tape timelines using Microsoft Excel is given in the Appendix of this article. An example tickertape timeline is shown below.

Example ticker-tape timeline

The essential components of this visual representation of the audio file are:

- A horizontal axis documenting time (in this case, seconds) from the start of the audio recording to its end

- Dots placed upon the timeline corresponding to specific sounds (in this case, primarily "Yip" calls made by the animal; but also other sounds interpreted differently, such as "Half yip")

- Ancillary information placed above (as seen here) or below (not illustrated here) the main series of vocalisations (in this case, periods during which foreground noise commenced and ceased - "Fore start"; "Fore End")

- A key explaining the notations used (ie. dots)

Where multiple files are being compared, as in this article, it is ideal to retain the same key across timelines - that is, the blue diamond should represent the same sound (in this case, "Yip") across all timelines being presented.

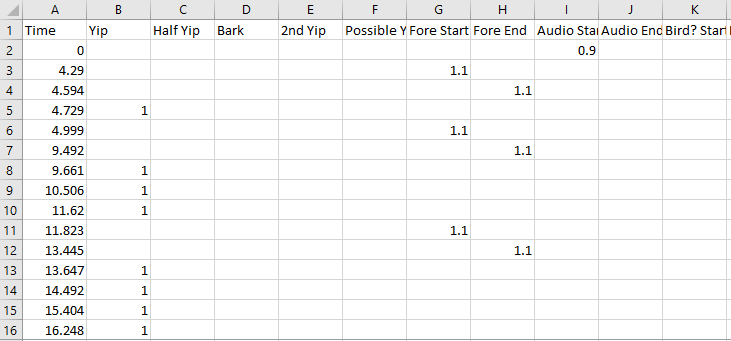

Ticker-tape timelines for word parts

The individual "word parts" (ie. "yips") within each recording were mapped to a timeline for that recording. This was carried out using Audacity audio editing software (version 2.1.2 for Windows). Audio files were imported into Audacity. iPhone files were converted from waveform display to spectrogram format. The Sony file was analysed in waveform format. Horizontal and vertical scales were zoomed to a degree that was sensible for interpreting the spectrograms and waveforms for each file. Files were played from beginning to end while listened to using a Plantronics USB headset (model Audio 628USB). The audio was frequently paused upon hearing a word part. The Selection Tool was used to click on the portion of audio where the word part was heard. If the spectrogram or wave form suggested a significant duration for the word part, then the beginning of the sound was clicked. The time of that word part was read from the status bar at the bottom of the Audacity screen. Notable events within the audio were logged with their timestamp and categoriesed into the following groups:

- Yip = a "yip" call is audible

- Half yip = a "yip" call is audible but the calling animal appears not to have given as much effort to the sound; a half-hearted attempt

- Yow = a notably different word sound - that is, more like a "yow" than a "yip"

- Fore Start = foreground noise in the recording commences, prospectively obscuring any interpretation of notable sounds while the foreground noise continues

- Fore End = foreground noise ceases sufficiently to be confident in interpretations of notable sounds after this point

- Possible Yip = a noise that may be a "yip" but is not sufficiently clear enough to be certain, due either to foreground noise interfering with interpretation or low quality of audio.

- 2nd Yip = a "yip" call is audible; many times it is very close in timing to another "yip" call (which would have been categorised as "Yip") and always it is of different pitch - interpreted to be a second animal calling near-simultaneously with the primary caller during this recording. In the case of isolated "2nd Yip" logs on the Sony audio (RB2), these also show lower peaks (lower volume) on the waveform inspection (see below) compared with the primary caller.

- Bird? Start = in one instance (CR3, 6.7 seconds from start) an apparent bird call sounding like a rapid "who-who-who" increasing in pitch, is heard in between the yip calls.

- Bird? End = see "Bird? Start"

- Double Yip = sounds like a single but stacatto word part - d-dah (the first syllable being very short)

- Unknown Start = In RB3, sounds like a growl - but more like a growling tummy than a growling dog

- Unknown End = see above

After pausing, playback was commenced, typically beginning a few seconds before the noise just logged.

By mapping these events on a horizontal timeline, a chart resembling "ticker-tape" is produced - hence the name "ticket-tape timeline" for the word parts of audio files.

The time difference between subsequent word parts was calculated (T2 - T1) and these differences compared between audio recordings made by Robert and Chris. In this way it was deduced that recordings CR1 and CR2 overlap RB1 (as described in Table 2, above).

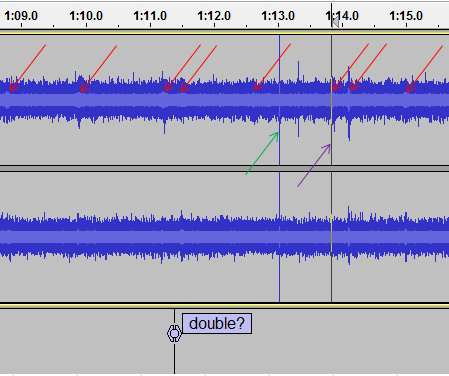

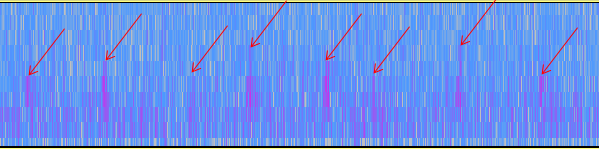

Sample waveform inspection

Figure 2 shows a section of the Sony audio file (RB2). The Sony file recorded in stereo format, so two wave form charts (blue horizontal bands) are shown (for left and right channels). The timeline within the file is given at top (from 1 minute, 9 seconds, through to 1 minute, 15 seconds). Red arrows have been overlaid for illustrative purposes and show peaks at the core of the wave form that correlate with audible "yip" word parts. The fourth red arrow indicates one of the "2nd Yip" sounds and has been labelled as such within Audacity using an additional (label) track (shown at bottom as "double?"). The green arrow illustrates a momentary spike in the volume of recording due to foreground noise and is heard as a "click" on playback. This did not affect interpretation of other sounds and is not logged in the ticker-tape timeline. The purple arrow illustrates the Selection Tool placement.

Sample spectrogram inspections

Figure 3 shows a section of an iPhone audio file spectrogram. The red arrows have been added for illustrative purposes and show peaks in the spectrogram correlating with animal vocalisations (ie. word parts). The peak indicated by the third arrow is not as pronounced as the others. Depending on how clearly the sound is heard on playback, this may be logged as a "Possible Yip".

CR1: Ticker-tape timeline

It can be seen between 3 seconds and 17 seconds that the rate of yipping is fast (ie. dots are less widely spaced), compared to that between 17 seconds and 28 seconds.

Table 5 shows the mean time (in seconds) between yips for rapid yips (3-17 seconds), slower yips (17-28 seconds) and overall (3-28 seconds) for a portion of the recording CR1.

| Measure | Between 3 - 17 seconds | Between 17 - 28 seconds | Between 3 - 28 seconds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.962067 | 1.349875 | 1.096957 |

| Median | 0.941 | 1.2745 | 1.073 |

CR2: Ticker-tape timeline

CR3: Ticker-tape timeline

CR4: Ticker-tape timeline

CR5: Ticker-tape timeline

CR6: Ticker-tape timeline

RB1: Ticker-tape timeline

RB2: Ticker-tape timeline

RB3: Ticker-tape timeline

Notes:

- The "Unknown Start" and "Unknown End" sound is like a growling tummy sounding like "growl"

- The "Bark" sounds like a lower pitched yip

- The "Double Yip" sounds like a stacatto d-dah and may be more related to the unknown sound than the yip.

- The portion from 3 seconds to 10 seconds is very interesting. In sequence it sounds like:

- a growl

- A low pitched yip

- A very short "who" sound where the 'o' is pronounced as in 'hot' (labelled "Bark" above)

- The common higher pitched yip

- A pairing of the higher pitched yip (first) followed immediately by the double sound "d-dah"

- The higher pitched yip continuing (from 10 seconds onward) - three regularly paced yips, then a slightly longer delay before the fourth yip

- Then apparent silence; four points have been marked "possible yip" - these sound more like a bark but are very low volume and appear to either come from some distance or, possibly more likely, be emitted very softly.

Expert opinions on the audio recordings

Nick Mooney - Wildlife biologist

Nick Mooney is a retired wildlife biologist with 30+ years' experience in the Tasmanian bush. He is presently a nature tour guide and technical advisor to the Raptor Refuge in Tasmania. He was a wildlife manager with the Department of Primary Industries in Tasmania for over 30 years prior to retirement, responsible for investigating claims of thylacine sightings for a considerable portion of this time and he was involved in the government led search spanning two years following the 1982 sighting by Hans Naarding.

Two of the longer audio recordings were played back to Nick, amplified, shortly after the conclusion of the trip. Nick only had this one opportunity to listen to the recordings and this was before any spectrograms or other investigation was commenced by Chris or Rob.

Nick said the call was "not anything [he] has ever heard before, in Tasmania or on the mainland" and that it was a good quality recording.

Nick dismissed fox, dog, all Tasmanian frogs and Tasmanian mammals. On subsequent communication Nick also dismissed sugar glider. His advice was to seek out opinions from owl experts.

Col Bailey - thylacine researcher

Col Bailey has been searching for - and researching - thylacines for 50+ years. He has published three books on the subject which include stories collected from "old timers" recounting their experiences from before 1936. In 2013 he published a book in which he recounts his own first-hand sighting of a Tasmanian tiger at close quarters in 1995. He also describes several other occasions during which he heard the Tasmanian tiger's hunting call.

Due to both Rob and Chris having departed Tasmania it was not possible to play the audio recordings back to Col first-hand. Due to the sensitivity of releasing a prospective audio recording of the Tasmanian tiger into the online world, a decision was made not to disseminate the recordings for expert opinions via online communications. However, on finding an independently published audio recording that seems to have captured a similar call, Col was asked for an opinion on that call. The similar call is described further below.

Col advised that "the thylacine hunting call is not a continuous yap but an extremely spasmodic one". His opinion was that it was probably a bird calling.

When asked whether the nature of the individual "yips" in the similar recording sounded like that of the thylacine, he replied "no".

Anonymous - thylacine researcher

An anonymous, independent thylacine researcher is noted for having 20+ years experience in the Tasmanian wilderness. The researcher has also spent some years studying birds in Tasmania. This is the researcher mentioned in the section on further calls on subsequent nights, above. After first hearing the audio recordings captured by Rob and Chris, this researcher subsequently spent time camping in the relative vicinity of the area in which Rob and Chris' recordings were made. The researcher heard a similar call, interpreted as the same species.

This researcher reported to Rob: "I was out camping ... and around 3am heard that animal sound you played me. The animal called for about an hour, repeating exactly the same sound and was some distance off ... but moved closer to within maybe 250m before slowly going away in the same direction. Apart from a possum earlier in the night there wasn't another sound made by another animal or bird all night. Very strange ... I have ruled out all the carnivorous animals here as none of them match that sound. The only other thing is a bird, and having studied Tasmanian birds for a couple of years I don't think it's any of those. I have been out in different parts of the Tasmanian wilds for 20 years and have never heard that sound before."

Marc Anderson - nature sound recordist and photographer

Marc is the owner of Wild Ambience and has published 32 albums of natural soundscapes since 2011. His audio recordings have been used in wildlife documentaries, films, musical compositions, museum exhibits, sound art installations and birding apps. He has contributed many sample recordings to the online database of bird calls at xeno-canto.org including those of the boobook owl and, identified in the background of some owl recordings, the sugar glider. In 2013 he launched a global project called Nature Soundmap which has collated over 400 audio recordings from over 90 sound recordists in 85 countries. A typical recording session for Marc will last from 20 to 50 hours and he reviews the entire recording before selecting samples for his albums.

For the same reasons as described above, the audio recordings made by Chris and Rob were initially not played back to Marc. Rather, Marc was also requested to listen to the similar recording that had already been published online. However, after compiling feedback from a number of sources, the audio from RB3 was played back to Marc.

Marc described the similar recording made by campers as "a typical Sugar Glider call". He noted that sugar glider "calls can vary a bit but generally the 'yip' sounds are spaced 1.2 & 1.4 seconds apart and the frequency [of the similar recording] is also spot on for Sugar Glider".

When queried on the discrepancy between spectrograms for known glider recordings showing peaks at about 4kHz and for Rob and Chris' recordings showing about 2kHz, Marc explained:

"The difference in frequency is likely due to both the recording quality and the distance from the source. Generally, sounds at the higher end of the spectrum get filtered out by obstacles between the mics & the source eg. trees. This means that sounds such as Sugar Glider calls recorded from a long distance, even with the best equipment in the world, will lose some of the higher frequency elements. They make calls of slightly different pitches as well, some have their fundamental element at about 1.7kHZ, others up to 3kHZ - but then there are harmonics above these as well, which are usually filtered out if heard from a distance."

Marc provided spectrograms for gliders he had recorded both at a distance and nearby, demonstrating the loss of signal at the higher frequencies.

Given the low volume and high background noise in Rob and Chris' recordings, a lack of discernible signal above 2kHz is explained by the reasoning provided by Marc. Hence the absence of high frequencies in the recordings does not imply that the recordings are not of gliders.

Regarding the previously published but similar recording, Marc reported glider yips to be spaced about 1.2 - 1.4 seconds apart. This is slower than the portion analysed from audio recording CR1 but in both the independent recording and those made by Rob and Chris, the rate of call decreases over time.

Regarding RB3 specifically, Marc again confirmed that the yip calls and also the lower pitched call at approx 6 seconds labelled "bark", match sugar glider.

Others

Other experts were consulted but did not wish to be named. These include two persons with wildlife audio recording experience, both suggesting sugar glider for the similar call mentioned earlier (ie. not Chris and Rob's recordings directly) and a lecturer in wildlife acoustics and recording, for assistance with interpreting spectrograms (who did not review any specific audio).

Searching for a matching bird call

Attempts were made to discover some documented description of a bird call matching the yips that were heard.

The xeno-canto.org website catalogues audio recordings of birds from around the world. The locaiton-based search was used for all recordings relating to the entire state of Tasmania. This yielded 54 species of bird which is not a comprehensive list for the area and many of which may have been implicitly excluded due to time of day or obvious discrepancy between usual calls and those recorded (eg. wrens). Regardless, audio was played back for all of the species listed in the Appendix below. Particular care was given to recordings of boobook owls where every available recording was replayed. None of the replayed audio yielded a match.

Questions were posted to the Australian Bird Identification group on Facebook. These included questions about the recorded yipping call (without sharing the audio) and questions about the "grooook" call heard after the yip calls ceased. No firm ID could be made on the yipping calls. After considering a number of waterbirds that may have matched the grooook call, it was found that boobook owl can in fact make such a call. Given the location of the search and the absence of any nearby significant water body, it is believed that boobook owl is a valid match for the call heard once the yip calls ceased. At the time of that call both Rob and Chris dismissed it as unrelated due to its differing nature, apparent nearness (relative to the yips) and overhead origin (compared with ground level origin for the yips).

Analysis of sugar glider calls

Several sugar glider calls were obtained from YouTube videos for the purpose of comparison, although all were from captive animals. As noted earlier, the spectrogram peaks were higher than in the Tasmanian recordings but this can be explained by the recording location and device. The timing of calls in Chris and Rob's recordings began at a faster pace than those on YouTube but was within range expected for a sugar glider, per Marc's response. "On paper", the sugar glider spectrograms offer the best match with the Tasmanian recordings, but as noted, it is possible for different animals to produce similar spectrograms. All else being equal, however, the sugar glider offers the best match when comparing spectrograms.

Flyovers

On two occasions during the sequence of events Chris noted wingbeats over the tent. On the second occasion, yip calls were also audible and Chris questioned in his journal whether the yip calls may have actually originated with the animal flying over the tent. By this stage in the sequence of events there was already considerable excitement regarding the yips originating near camp and their being recorded; it is difficult to gauge whether the simultaneous flyover and yip calls were related or whether that assessment was affected by the excitement of the moment.

If the second flyover and yip calls are taken as related, this presents strong evidence of an avian origin for the calls. However, all assessments of the calls' directions and the wingbeats flying overhead were made from within a tent. The tent itself may have affected such assessments. During discussions the following morning there were discrepancies between the directions perceived by Rob and Chris, with Rob estimating that the yipping calls had come from four points around the camp, while Chris verified 2 points opposite each other for some calls but was unable to discern direction for others. Whilst comparing other details observed (such as the presence of a double-yip and the changing pitch between locations / animals) it became clear Rob's assessments for direction were likely to be more reliable than Chris'. Bearing this in mind it should be noted that Robert gauged the yip calls to be originating at ground level.

Speculative thylacine interpretation of events

At the time of events, both researchers were excited at the calls being heard. They were in the field specifically to look for evidence of the thylacine and, along with any other modern-day researcher, the only information they had to go on regarding thylacine calls, was a set historical written descriptions. Both had been to Tasmania many times over the prior ten years; both in search of the thylacine in remote Tasmanian wilderness; and neither had heard a call that could so clearly be described as a 'yip' before.

The first yips (event A) sounded "tentative". They were only brief. However they were so close to camp that it warranted spotlighting in the direction of the call to try and sight the animal that made them. During this period of spotlighting the second set of calls was heard, but this time from a distance, across the valley. In the hope that these calls may have been made by a thylacine, it was easy to speculate that the first call came from a young thylacine - perhaps vacating the den on nautical twilight - and that the second, a few minutes later, came from an adult making reassurance to its young. It has been noted before that the Tasmanian wilderness is generally incredibly quiet, even at night. There is no loud chorus of insects or frogs to fill the air; rather, it is the occasional sound that stands out against a backdrop of silence.

After discussing the two sets of calls in the context of each other, the pair retired and it wasn't for almost another hour before the calls began again. However this time they were again close to camp and near their first location. Over almost an hour these calls seemed to encircle the camp. Rob's first speculation was that it took the adult thylacine that amount of time to return from the other side of the valley, on hearing its young's call. On arriving at our camp which, coincidentally, had been set up right where its young were hidden in a den, that parent then circled our camp - perhaps to indicate the boundary where the young may not cross. Chris speculated that alternatively, the adult may have been attempting to move the human interlopers on from this location. As it appeared that two differently pitched calls were heard from different points around the camp. This may have indicated two animals attempting to move on the humans.

However, how realistic is it to conclude that this extensive interaction may have come from the Tasmanian tiger? Historical accounts appear conflicted. While there are some reports of thylacines being curious about human encampments - venturing to the edge of firelight, for example, or that thylacines followed hikers for days on end, the majority of accounts describe the thylacine as shy, fleeting, retiring, intelligent and secretive. It would be extraordinary - and previously undocumented - to have had one or more thylacines calling repeatedly over the course of an hour within just metres of a camp. On the other hand, there are very few historical accounts involving humans interacting with thylacines at a den site with young animals present.

Thylacine breeding cycles and parenting behaviours

Research has been carried out on thylacine breeding seasons. Sleightholme and Campbell report that a comprehensive assessment was carried out by Eric Guiler in 1961 but contend that anomalies in Guiler's bounty records source data undermine his conclusions. By analysing newspaper reports, zoo and museum records, Sleightholme and Campbell propose a new model for thylacine breeding seasons.

A key finding in Sleightholme and Campbell's paper that relates to this present analysis is the conclusion that females carry pouch young between the months of May and December. This implies that by January, young thylacines are, for the first time, permanently leaving their mothers' pouches.

If an interpretation of thylacine is entertained for these audio recordings, and more particularly, if an interpretation is entertained that the calls from event A are from a young thylacine, then the date of this expedition, being late February, coincides with the first two months during which thylacine young are permanently leaving their mothers' pouches.

Further, thylacines were known to leave their young in the den while the adult goes out to hunt which may correlate with the interpretation of events A through C given above, that a young animal called tentatively; an adult soon replied; the adult then took time to return from afar before beginning a persistent call.

Thylacine vocalisations

Regarding the nature of the persistent, single 'yips', some historical accounts do describe the thylacine as yapping persistently and others describe it as yapping briefly but periodically with double-yips. On some occasions this call is referred to as a 'yip' and on others, a 'yap', much like a small terrier. The 'yip' calls heard by Chris and Rob did sound similar to those of a small dog, such as a terrier and very much fit the description of 'yip'. The distant calls of Event B however better matched those of 2013 which were paired vocalisations and described as 'tew-tew'; in Chris' opinion, this call matches the thylacine's description of "coughing bark".

Independent recordings speculatively identified as thylacine

Whilst researching animal vocalisations that may match our recordings, a recording was found on the Thylacine Research Unit (TRU) website having a very similar call. The original recording runs for over 6 minutes and was allegedly created by undisclosed persons camping in Tasmania. Much of the audio has significant foregound noise obscuring the call of the animal (or animals) in question. However some portions provide clear audio of the animal call. TRU's conclusion was that "just as there is no way to prove this record is thylacine, there is no way to prove that it isn't. Whilst TRU, believe it most likely is NOT thylacine, however, remote the chances - this could be the sound of hunting thylacine."

Four excerpts from the original recording have been extracted and collated into the audio below. During the third excerpt, a "2nd Yip" (as described above) can be heard almost simultaneously with the primary caller. If this recording is of the same species, then it would appear in both instances the calling animal was in the company of a second, less vocal animal. Could this be a relational or breeding call between sugar gliders, owls, or thylacines? Or a parental call between adult and young thylacines?

This recording was received by the Thylacine Research Unit on 31 March 2013. If this was forwarded to the Thylacine Research Unit soon after the camping trip, this would put the call within 4 weeks of the same date (but in 2013) on which Chris and Robert recorded a similar call in 2017.

At least one of the unidentified campers can be heard concluding the animal is a Tasmanian tiger.

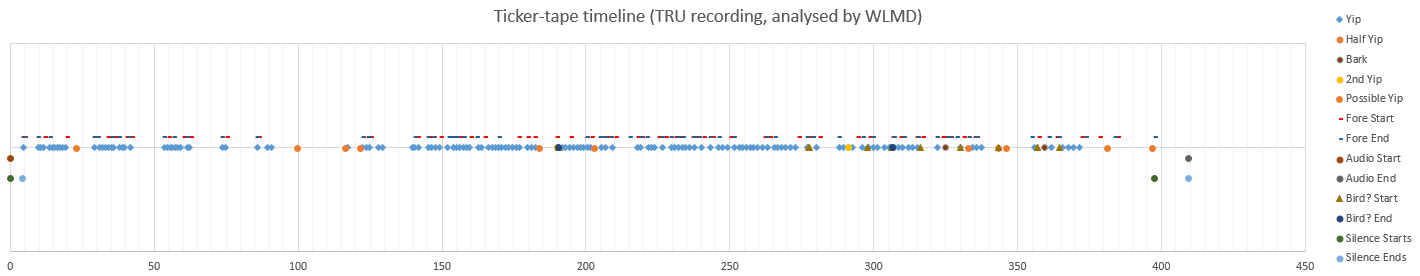

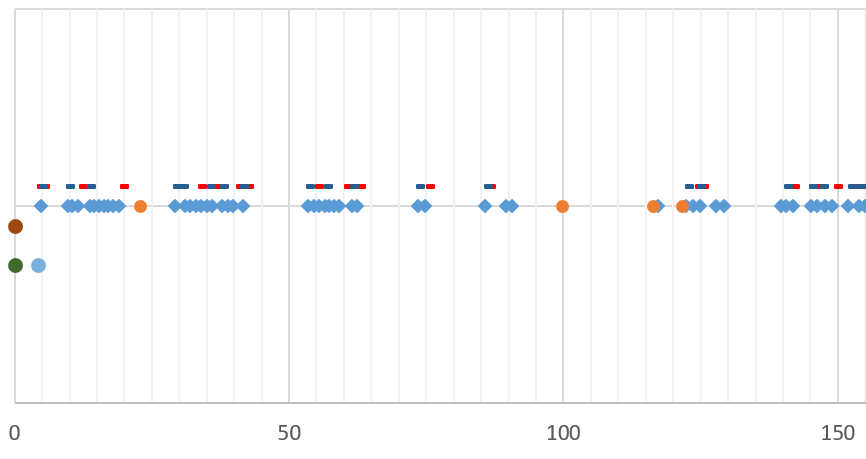

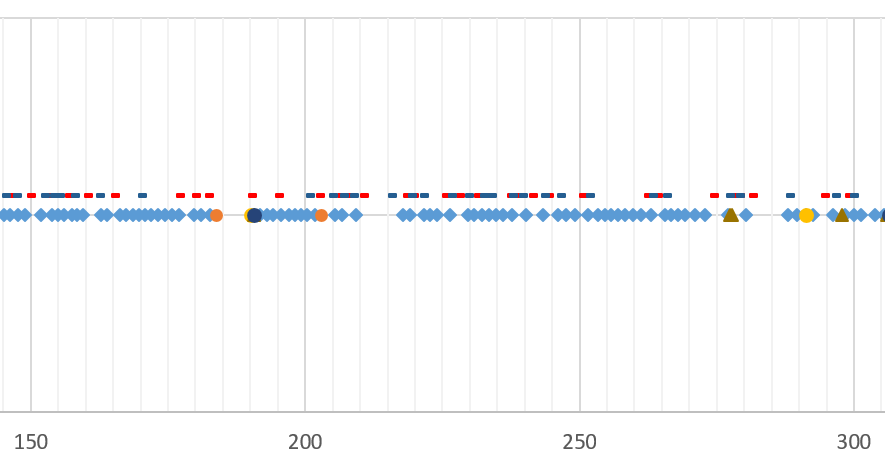

TRU: Ticker-tape timeline

The TRU recording lasts over 6 minutes. There are at least 3 origins for various sounds in the recording:

- Humans (the recordist; other campers; movement of sleeping bags, zippers, etc; possibly some of the unidentified sounds originate with the campers)

- The unknown animal "yipping" and, at least once, possibly twice, "barking"

- Prospectively, a bird or birds (unusual sounds not necessarily obviously avian, but possibly avian)

For extended portions of the recording, sounds of human origin interfere with the ability to hear other sounds, or outright drown out other sources due to the high volume of human-produced sounds. As such, an interpretation of this recording is quite complex - there are many individual events during the recording (such as the start or end of human sounds obscuring interpretation of any other source of sound). There are also many unidentified sounds. The "yipping" call clearly constitutes the majority of sounds from an unknown animal but there is a significant number of other sounds - presumably not of human origin - that do not match the yipping call and may be made by a different animal.

In one instance there appears to be a double yip (marked "2nd Yip"), similar to that found in RB2. In two instances a barking call is heard, the timing of which suggests it is made by the same animal that is yipping but the nature of the bark is very much more dog-like. This last point is notable.

The full ticker-tape timeline is presented below as a single image with low resolution. Note the red and blue bars above the yip calls represent the start and end of foreground noise that obscures the animal call.

Ticker-tape timeline of recording published by TRU

Due to the duration and complexity of this recording, the ticker tape is presented as three separate, overlapping sections, each spanning at least 150 seconds. These are presented in thumbnail format. Click on the thumbnails from a desktop browser to open full-size versions in gallery view.

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|

It is key to note that the sounds labelled "Bird? Start" and/or "Bird? End" are extremely tentative - in some instances these sounds do not obviously sound like a bird.

Analysis of campers' recording

Notable sounds during the timeline include:

- 190s labelled "2nd Yip" is higher pitch

- 277s labelled "Bird? Start" sounds like a very quick "oo-oo"

- 289s labelled "Yip" - the pitch and volume appear to change

- 291s labelled "Yip" and "2nd Yip" is a double call - near simultaneous, but not simultaneous. The second call is qualitatively different: louder; longer; and more like a bark

- 297s labelled "Bird? Start" sounds like a squeak

- 305s labelled "Yip" sounds like a higher pitch squeak, as if the caller's voice is breaking

- 306s labelled "Bird? Start" and "Bird? End" (duration 0.24 seconds) sounds like a human exclamation of "argh" but is immediately followed by inhalation of breath and does not appear to relate to the humans making the recording

- 316s labelled "Bird? Start" sounds like a loud squeak, very near; partially intelligible human voice immediately after mentions "take that to the bank" - prospectively meaning the call just heard is interpreted as being of value. (In the context of other things spoken, the recordist seems convinced he is recording a Tasmanian tiger. See next bullet point.)

- 324s labelled "Bark" is a very definitely dog-like bark. Human voice immediately after is clearly excited to have captured that vocalisation on audio (swearing "F*** yeah") suggesting the recordist is convinced they are recording a Tasmanian tiger.

- 330s labelled "Bird? Start" sounds almost like a split-second vocalisation by a human rather than a bird, but is not clearly identifiable

- 343s labelled "Bird? Start" is a loud click - not clear if human in origin or not

- 354s labelled "Fore End" means foreground human noise has ended sufficiently to hear other sounds. However, in this instance there appears to be a digital beeping reminiscient of a morse code signal in the pattern of "beep beep ... bip bip beep bip bip ... bip bip bip". This is heard over the top of human breathing and the background yipping.

- 356s labelled "Bird? Start" is a click

- 357s labelled "Bird? Start" is a click

- 359s labelled "Bark" is a possible bark

- 364s labelled "Bird? Start" sounds like "cheek" - not clear on origin

The single vocalisation at 324 seconds, if heard on its own, is convincingly dog-like.

Due to the extensive foreground noise, it is difficult to identify a continuous sequence of yip calls of significant length that is unambiguously not overlaid by foreground noise. Three short sections of the recording were analysed where there was no ambiguity created by foreground noise, for mean and median durations between yip calls.

| Sequence | Beginning | Number of yip calls | Mean time between yips (seconds) | Median time between yips (seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 167.364 | 3 | 1.114667 | 1.064 |

| 2 | 171.958 | 4 | 1.24125 | 1.241 |

| 3 | 253.385 | 7 | 1.368143 | 1.317 |

These values suggest the calls on the campers' recording are generally slower than those on the Rehberg and Bagshaw recordings. However it must be said these are snapshot samples and do not constitute a comprehensive analysis. Further, the campers' values are taken at least 160 seconds into the recording, compared with 3 seconds for CR1 (above). In all recordings (Bagshaw, Rehberg, and published by TRU) the rate of call slows down over time.

Comparison with the Rehberg Bagshaw recordings

In common with the Rehberg Bagshaw recordings, the campers' recording exhibits the following:

- A double-yip seemingly originating with two separate animals

- The two separate animals having different pitch

- "Non-standard" yips, by which is meant: the majority of yips are consistent in audio quality. In the case of the campers' recording there is a higher pitched squeak (at 305 seconds) sounding like a voice breaking; In the case of Rehberg and Bagshaw there are some yips given apparently half-heartedly.

- The vocalisation event persists for minutes (6+ in the case of campers; 4, 4, 4, 6 in the case of Rehberg and Bagshaw)

- The pace of the yipping decreases over time

- A background sound tentatively identified as avian is present in both ('who-who-who' in CR3; 'oo-oo' in TRU)

As noted above, the campers' rate of call appears slower than that in CR1 but the campers' sample comes from 160+ seconds into the recording, whereas the CR1 sample is from 3 seconds onwards.

Conclusion on the independent recording

Due to the similarities listed above, it seems reasonable to conclude that the animal(s) recorded by the campers in 2013 are of the same species as those recorded by Bagshaw and Rehberg in 2017.

Additional independent recordings

Just prior to publication, this author became aware of further independent recordings of similar vocalisations. Although these are not analysed here, they are notable for being recorded within a few weeks of the Rehberg, Bagshaw and TRU recordings - but in a different year. They were also recorded in a completely different region of the state, separated by some of the state's most settled areas. If the species in these independent recordings is the same as that recorded by Rob and Chris, this would tend to lend weight to a glider or owl origin rather than two separate populations of thylacine persisting, each undetected, or a single population migrating without detection across some of the most settled areas of the state. However a firm conclusion cannot be drawn concerning these recordings without a rigorous analysis, so the implications of these recording are, at present, speculative.

Conclusion

There are many aspects to this series of events which must be considered in proposing an identification for the caller.

While each given species may seem more likely given some of the circumstances, other circumstances are not easily explained. A summary of facts and details contributing to an identification is presented below.

| Factors supporting this ID | Factors against this ID | |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar Glider |

|

|

| Boobook Owl (or other bird) |

|

|

| Tasmanian tiger (thylacine) |

|

|

Identification

In truth, an identification of the caller remains inconclusive.

There is no known audio recording of the thylacine with which to compare the present recordings.

In Chris' opinion all calls from events A, C, D, E, F & G are more likely to be a sugar glider or an owl than they are to be thylacine but the call from event B (not recorded) better matches thylacine than glider or owl (and also matches the call heard in 2013). Chris notes:

The identification of glider sounds compelling based on spectrogram similarity and expert opinion, but then different calls may produce similar spectrograms and localised expert opinion favours an avian origin. The presence of wing beats and bird vocalisations suggest an owl may have been present, but then two of the same localised experts are also bird experts and both reported never having heard this call before. As such, Tasmanian tiger remains a viable explanation if it can be accepted that the length of the encounter is explained as an otherwise previously undocumented behaviour; undocumented, possibly because of limited data on behaviour in the wild and/or limited data on thylacine behaviour during the initial weeks upon which young leave the pouch. The dog-like bark in the campers' recording is also not easily explained with an avian or glider origin. Even if events near camp remain ambiguous, if Event B is considered as unrelated to the events near the camp, then the differing nature of the call ("tiu" vs "yip"), the presence of a double word-part, the deduced distance of the call exceeding 1km and the brevity of the call (just 6 or 7 word parts) lend greater support to this vocalisation on its own originating with a Tasmanian tiger (and likewise for the 2013 call). Revelation later in the year that a similar call was recorded from a different area of the state suggests that if the call belongs to a thylacine, then the thylacines must persist in at least two discrete locations, or else be migrating across some of the islands most inhabited areas without detection. For this reason, sugar glider and owl again seem the more likely candidates for all calls except Event B.

In brief, Chris believes that the calls of Event B and 2013 are the best match for a thylacine. This call type warrants further research and effort to record it and identify the caller. The remaining calls from 2017 are more ambiguous, with owl being more likely than glider, if not thylacine. Regardless of species, it is clearly an uncommon call and would be of interest even if the caller was not thylacine. As such, further recording attempts - for both call types - are warranted.

In Rob's opinion the identification of Tasmanian tiger is viable and supported by elements such as the cracking twig, a ground-level origin for the calls, some reports of the thylacine calling continuously and the word parts ("yip") matching written descriptions for the species. An interpretation of one or more young thylacines exiting a den near base camp and an adult responding from a distance fit the differing nature of calls near the camp compared with those from a distance and provide a viable explanation for the continuous yipping and lack of double-yips near camp.

Further research

Both Chris and Rob intend further expeditions in search of the thylacine. By agreement, each will return to their original approaches of working independently in future.

Chris plans to check the cameras deployed on this expedition and to deploy automated audio recording devices along with cameras, resources pending.

Contacting the researchers

To contact Rob, visit his YouTube channel.

To contact Chris, use the contact form on this site.

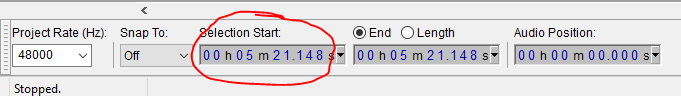

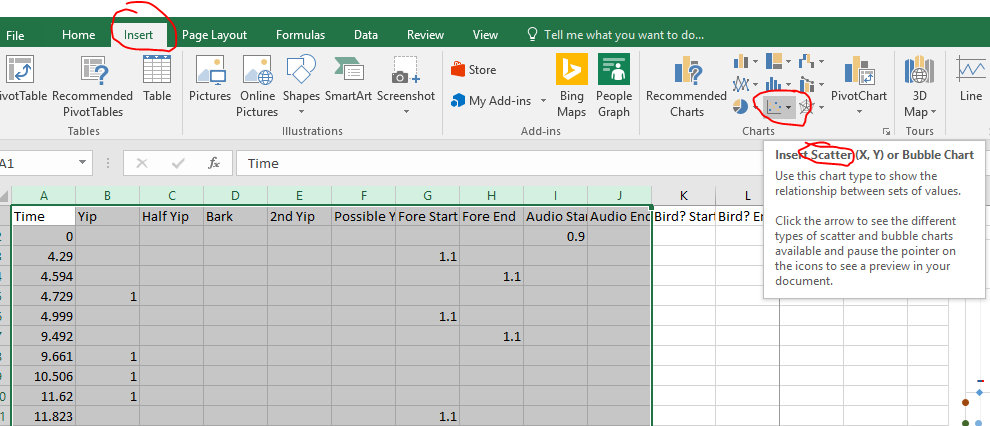

Appendix 1: Creating ticker-tape timelines - a method for documenting animal calls in audio recordings

During this analysis, "ticker-tape" timelines were presented for showing the sequence of sounds in each recording. A brief description of the methodology involved for preparing these charts is given below.

- Use Microsoft Excel to prepare a worksheet. Example screenshot:

- The first column is headed "Time"

- Subsequent columns are headed with events of interest (eg. "Yip", "Half Yip", "Fore Start", "Fore End", etc). The order in which you label columns is the order in which they will appear in the chart legend.

- Play back the audio using a headset in a quiet environment and listen for sounds you wish to document - in this analysis, Audacity was used.

- If required, zoom the vertical axis (click on the vertical axis, as many times as required) to increase the size of the wave form in waveform view (or the spectrogram in spectrogram view)

- If required, zoom the horizontal axis (click on the magnifying glass in the toolbar, as many times as required) to increase the width of the waveform

- When sounds of note are encountered, pause the video, and with the Selection Tool active, click on the start of the sound.

- Read the "Selection Start" time from the status bar at bottom of the Audacity window:

- Convert minutes to seconds and record this time in the first column (ie. 5m 21.148s becomes 321.148)

- Decide where on the ticker-tape timeline you want to position a marker for this sound. In this analysis, the "yip" calls are the primary call of interest and these are positioned on the horizontal centre line of the chart.

- To position a marker on the horizontal centre line, use the value '1'

- To position a marker below the centre line, use a value between 0 and 1. The smaller the number, the lower the marker. ("Audio start" shows 0.9 in the screenshot above)

- To position a marker above the centre line, use a value between 1 and 2. The higher the number, the higher the marker. ("Fore Start" shows 1.1 in the screenshot above; "Fore End" also shows 1.1 and is the same distance above the centre line in the final ticker-tape timeline).

- Repeat with other sounds of note (eg. the end of a long sound, etc).

- In theory the rows in the spreadsheet can be in any order, but it is helpful to list events in chronological order - this allows you to perform calculations between rows (like duration between yip calls). It also allows you to use a "Notes" column for writing notes about the audio recording, then later, reading those notes in chronological order

- Once you have entered a few (or all) rows of data, select all reportable columns (by clicking and dragging along the column headers - above the first row of data) and insert a Scatter Plot chart into the worksheet (by clicking the "Insert" group in the Ribbon, then locating the Scatter Plot chart icon:

- At this point, force the y-axis to use a minimum value of 0 and maximum value of 2

- Remove the y-axis labels

- Add a legend (under Design group on the Ribbon)

- If you want to reformat any of the markers, right-click on the marker in the legend and choose "Format data series". Somewhere under these options (depending on version of Excel) you can modify the marker shape, colour, size, fill.

- If you want to display the vertical gridlines on the chart area, insert these from the Insert group on the Ribbon

- Insert and customise a chart label likewise.

Appendix 2: Tasmanian bird call recordings

The xeno-canto.org website catalogues audio recordings of birds from around the world. The locaiton-based search was used for all recordings relating to the entire state of Tasmania. This yielded 54 species of bird, many of which may have been implicitly excluded due to time of day or obvious discrepancy between usual calls and those recorded (eg. wrens). Regardless, audio was played back for all of the following species. Particular care was given to recordings of boobook owls where every available recording was replayed.

- Pacific Black Duck (Anas superciliosa)

- Chestnut Teal (Anas castanea)

- Little Penguin (Eudyptula minor novaehollandiae)

- Short-tailed Shearwater (Puffinus tenuirostris)

- Tasmanian Nativehen (Tribonyx mortierii)

- Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris)

- Masked Lapwing (Vanellus miles)

- Pacific Gull (Larus pacificus pacificus)

- Brush Bronzewing (Phaps elegans)

- Shining Bronze Cuckoo (Chrysococcyx lucidus)

- Pallid Cuckoo (Cacomantis pallidus)

- Fan-tailed Cuckoo (Cacomantis flabelliformis)

- Australian Masked Owl (Tyto novaehollandiae castanops)

- Southern Boobook (Ninox boobook novaeseelandiae)

- Morepork (Ninox novaeseelandiae leucopsis)

- Musk Lorikeet (Glossopsitta concinna)

- Green Rosella (Platycercus caledonicus)

- Orange-bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster)

- Eastern Ground Parrot (Pezoporus wallicus)

- Superb Lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae)

- Superb Fairywren (Malurus cyaneus)

- Southern Emu-wren (Stipiturus malachurus)

- Tawny-crowned Honeyeater (Gliciphila melanops)

- Crescent Honeyeater (Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus)

- New Holland Honeyeater (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae)

- Strong-billed Honeyeater (Melithreptus validirostris)

- Black-headed Honeyeater (Melithreptus affinis)

- Yellow-throated Honeyeater (Nesoptilotis flavicollis)

- White-fronted Chat (Epthianura albifrons)

- Little Wattlebird (Anthochaera chrysoptera)

- Yellow Wattlebird (Anthochaera paradoxa)

- Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala)

- Forty-spotted Pardalote (Pardalotus quadragintus)

- Scrubtit (Acanthornis magna magna)

- Striated Fieldwren (Calamanthus fuliginosus)

- Tasmanian Scrubwren (Sericornis humilis)

- Brown Thornbill (Acanthiza pusilla diemenensis)

- Tasmanian Thornbill (Acanthiza ewingii)

- Yellow-rumped Thornbill (Acanthiza chrysorrhoa)

- Black Currawong (Strepera fuliginosa)

- Australian Golden Whistler (Pachycephala pectoralis)

- Grey Shrikethrush (Colluricincla harmonica)

- Grey Fantail (Rhipidura albiscapa albiscapa)

- Satin Flycatcher (Myiagra cyanoleuca)

- Forest Raven (Corvus tasmanicus)

- Dusky Robin (Melanodryas vittata)

- Pink Robin (Petroica rodinogaster)

- Flame Robin (Petroica phoenicea)

- Tree Martin (Petrochelidon nigricans)

- Silvereye (Zosterops lateralis)

- Bassian Thrush (Zoothera lunulata)

- Common Blackbird (Turdus merula)

- Australian Pipit (Anthus australis)

- (?) Identity unknown

Citing this article

Rehberg, C. (2017). Rehberg Bagshaw audio recordings analysis, Accessed: date, http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au.