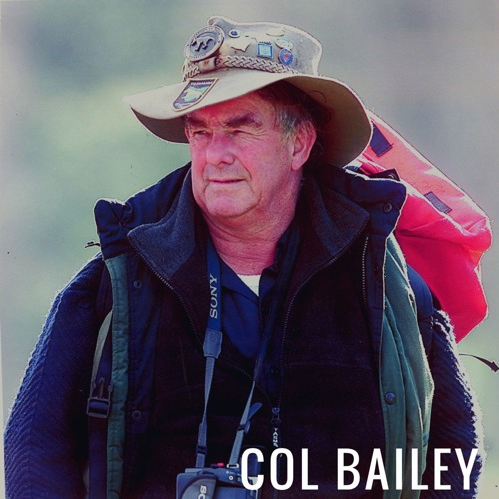

Col Bailey - interview with Hanny Allston

This article is a transcription of a podcoast interview conducted by Hanny Allston with Col Bailey originally published 19 Sep 2017. Transcription by Chris Rehberg. Podcast content reproduced with permission.

Hunting for the Tasmanian Thylacine with Col Bailey

Introduction

Hanny: Ok, so, I think this is the most excited I’ve been for a very long while. I am so, so thrilled to be introducing you today, to Col Bailey. Col is actually a retired landscape gardener and an avid bushwalker and back in the day, he used to absolutely love to canoe and was even the Australian fifty mile walk, race, record holder. So he’s a pretty good athlete really, in his own right.

It was in early 1967 that he was paddling in his canoe on the Coorong (sanctuary area) in South Australia when he chanced upon a Tasmanian Tiger. So 1967 is well after the supposed extinction of the Tasmanian Tiger in the 1930s, but Col has become the go-to person for anyone who believes that they have seen or heard a Tasmanian Tiger. And he’s really made it his life’s calling to prove to the world that this incredible animal can still exist here in Tasmania.

In this podcast we delve deep into sightings of the Tasmanian Tiger here in Tasmania, including Col’s own sightings in 1993 and 1996. His books “Tiger Tales” and “The Shadow of the Thylacine” have been a raging success and we actually now sell them here, at Find Your Feet, in our retail store in Hobart.

Col lives in Tasmania and sadly he is not a very well man anymore. It was quite an honour to be given one hour of his time to sit and pick his brains on how and where the Tasmanian Tiger still exists.

Look, I was a bit of a skeptic, before I read any of his books. I am an avid believer now that I have read this book and I have had this chat with Col Bailey.

Our audio was a little bit interrupted because we need to give Col time to catch his breath during the podcast, but I know that you are going to be engrossed in this, no matter what, and are going to come away desperate to know that the Tasmanian Tiger still exists and desperate to see one with your own eyes, so let’s get right into it: Hunting for the Tasmanian Thylacine with Col Bailey.

Interview

Hanny: Rolling! Col, Thank you for making the drive down to Hobart to visit me.

Col: My pleasure.

Hanny: This is really exciting. I must say I potentially have been bragging to a few people in the store as they pick up your book and browse through it, that I was planning to broadcast you and that we had you lined up. There’s not many occasions where I can sit in one place for a prolonged period of time but when I came across your book on a holiday up at Coles Bay, I have to admit that eight hours later I was still curled up on the couch.

Col: Amazing.

Hanny: So, it really - for those of you who haven’t read Col’s books, we’ll put some links to them on the podcast pages, but I can absolutely vouch it’s a phenomenal read and it will - I don’t know, I’m an avid believer now that the Thylacine still exists.

Col: That’s good.

Hanny: Yeah. I’m really interested to know, just at the outset, like - you talk a lot about your own experiences in the book as well as other people’s sightings. You’ve kind of become, to some degree, the go-to person if you believe you have seen it or had an experience with a Thylacine. How many times have you personally - feel that you may have come into contact or been in the same region as a Thylacine?

Col: Well, definitely in 1995 and perhaps in 1997 [sic - 1967] along the Coorong in South Australia. I didn’t know what it was, but investigations into what it could have been led me to the Tasmanian Tiger. I knew very little then, about it, and there were other people seeing the same sort of animals being roundly called a Tasmanian Tiger in the Adelaide Advertiser. And, ah, that may be - I don’t know, but what it did was start me on this caper, searching for the Tiger and proving to the world it still exists, but ‘95 was definite. And up ‘til then I was in two minds; I thought it could exist, it may not exist. I was like so many others - I wasn’t sure; I was hoping. Ah, but then I was led into that area by an old bushman who said they definitely were in there, and when I seen it with my own eyes, I knew, but for seventeen years I didn’t tell a soul, not even my wife. And she wasn’t very happy when she found out when I was starting to write the book. She said “I thought we had no secrets” and I said to her, “Darling,” I said “better a love affair with the Tasmanian Tiger than another woman!” And so I told no-one, to protect the animal, because I was so fearful of what could happen if people got in there. And there are hunters that would shoot them on sight. They’ve told me that, and Nick Mooney and I have both had this experience of being told by people that they will shoot them if they see them. And so I want to protect the animal, so the second time (in ‘95) was without doubt in my mind, and that woke me up to the fact that they were there. And people say “How can you be so sure? How can you talk like you do and say, you know, ‘there’s no doubts that they’re there'?” I said “Because I know. I’ve seen - I’ve seen the thylac- I know they’re there”. And so how much more definite could you be than that? I mean I’ve seen the thing, and ah, many people see an animal and they think it’s a Tasmanian Tiger but they’re not sure. And a lot of these people don’t know very much about them at all, and it could be a dog, it could be - and on the mainland, of course - a fox; a mangy fox. They’re seeing mangy foxes over in South Australia at the moment and there’s a certain fellow over there that capitalizes on this - “Oh yeah, it’s a Tasmanian Tiger” - but they’re not at all. I’ve seen the footage, and they’re not. So, ah, no. That’s - once - but I’ve smelt them; they’ve got a definite odour, and I’ve smelt them several times, and I’ve heard them calling in the bush on three or four occasions.

Hanny: Ok. I’m really - you know, I hear what you say about how you kept all this a secret, even from your wife, for a prolonged period of time because - you mentioned that a few times in the book: you were worried that by releasing your knowledge and the belief that you knew that they still existed here, that you were endangering the species itself. What changed then? How did the book come about then?

Col: Well, I really wanted to wait until I’d proven to the world that the Thy- exists, but time was running out. I was getting older and older, and less able to get out into the bush, where I wanted to go, and I thought well maybe it’s time to write the book. I left it until the very last moment. My agent said “You know, you’ve gotta liven this thing up” and I said “I can liven it up”. I said “I don’t really want to yet” and he kept at me and at me and he said - ‘cause I’d had him for the first book, Tiger Tales, back in 2001 and ah, he knew where I stood and he had faith in me and he said “Look, if you’re gonna liven this book up…” and I said “Yeah, I can liven it up” but I said “I’ve resisted this”. So eventually, I let it go. And I - even then I didn’t really want to but, ah, so, I told the full story, and he said “Now, this is what we love; this is what we want” and we showed it to the publishers and they said “Oh, we’ll jump on this, yes.”

Hanny: But you weren’t writing this book to become famous…

Col: No, no, no, no, no - I just wanted to tell my story.

Hanny: Yeah, to tell your story.

Col: If I wanted to become famous I could run to the papers with my sighting, and a lot wouldn’t have believed it, but I don’t like taking this to the newspapers. The media are very dangerous because they sensationalise it, and in this instance they have done, on a number of occasions. And people have gone in there with guns and tried to find it and shoot it! And I didn’t want that to happen.

Hanny: The Thylacine is a bit of a hot topic at the moment. It’s been reported in the media that has been sightings in northern Queensland and in South Australia but we’re talking about the Tasmanian Tiger, so I guess I have a couple of questions. One is, are we talking about the same species? Is there a possibility that they're on the mainland as well, or - yeah, can you describe a little bit more about the Tasmanian Tiger and where you believe it still exists?

Col: Well basically, it is the same animal, basically. The Queensland situation is slightly different. Now there’s supposed to be an animal up there that is a variation of our Tiger. Some have said the stripes go underneath, not over the back, and there’s a lot of contention up there as to, you know, what sort of an animal it actually is. But I doubt, if one was found in Queensland, [that] it would be like our tiger; it would be different.

Hanny: But there’s no record of any animal, no visual proof or any evidence, is there, that there is a Tiger up in the Queensland area. I mean we know for a fact that pre-1937 when the Tiger became extinct, that - you know - Tigers did exist in Tasmania, we have all the evidence of that, but Queensland? Different situation?

Col: Well they did - they did exist in Queensland many, many thousands of years ago. As my friend Mike Archer has proven, the Riversleigh deposits and that. There’s been instances of them being found in every state but basically in Australia. But this is millions of years ago - or thousands, many thousands of years ago. And, ah, but now, today, in this age I think if they were to be found anywhere on the mainland it would be in Western Australia.

Hanny: Western Australia?

Col: Vast areas there that really are still to this day, basically undiscovered. And, um, they found that one on the Nullarbor in the mid sixties - a desiccated specimen, they called it. And then the fur, and the teeth and the eyes are all there! And this animal at the bottom of a sink hole. It looked like it had only just dropped down there twelve months before. And yet they were saying it’s three thousand something years old. So they definitely were on the mainland, but in this day and age, I don’t know - as I say: the one on the Coorong, South Australia - I’m not sure to this day what it was. It was something strange, but if nothing, that started me off on this, this-

Hanny: Yeah, ‘cause the Coorong sighting was your first ever experience confronting a Tiger and you talked quite at, quite length in your book about that sighting. You were just out recreating in the area and suddenly saw an animal that you couldn’t really, um, describe.

Col: I was a recreational canoist. And I was looking for emu that morning. Instead I see what I thought might have been a Ta- I didn’t know what it was, and I went to the local garage and told him on the way home. And a friend of mine had a dairy along the Coorong. I used to stay there and he, he wasn’t home when I got back with the canoe, so I went - packed it up and went back through Maningie and I told the local tourism bloke. “Yes, oh you wouldn’t be the first one to see that”, he said, “there’s been plenty in here saying they’ve seen that sort of animal.” He said “There’s a fellah up the road”, and as I say in the book, “go and have a talk to him”, so I did. And it’s - it all added up. He’d seen the same animal that I thought I’d seen. And the Advertiser in Adelaide - the paper in Adelaide - was calling it a Tasmanian Tiger. So the general belief [was] that it was there, and - dozens and dozens of sightings. I started hunting some of them down, and interviewing them. And, ah, it all built up and I was going out (?) with quite a dossier and then, when I got to Tasmanian of course, I went to see a bloke called Elias Churchill who is on record as hunting the last - capturing the last tiger, the last one in the Hobart Zoo that died in 1936. And he opened my eyes to a lot of things. And then I started hunting down the old Trappers and Bushmen.

Hanny: In Tasmania?

Col: Yes, yes, mainly in Tasmania. A few of them on the mainland, but ah mainly in Tasmania, and I was flying back and forwards and it was driving me silly, so eventually, come over here to live.

Hanny: So before all this came about, had you - were you working in any particular industry? Like who was Col before that first sighting?

Col: Just arbor/landscape gardener.

Hanny: Yeah really? In Adelaide?

Col: I was an athlete of course, and that was my main love - athletics, but then, ah, I was a landscape gardener and as I got older, I liked the canoe - canoing and stuff, so, you know - you take on different things as you get older. But this, when this thing came along, it was the thing that captured my imagination.

Hanny: Yeah, 'cause I was going to ask you - what then drove you to, I guess, you know, become someone who wanted to prove to some degree that the Thylacine still existed? Was that what was driving you then? Or was it curiosity? Was it love of Tasmania? Was it a bit of everything?

Col: Well, I was getting kicked from pillar to post by certain people in the scientific community, that I was a nutcase.

Hanny: I have no doubt.

Col: And I formed a good friendship with Eric Guiler - he was recognised world authority on it, here in Hobart. And Eric was getting kicked around-

Hanny: Is he the one that was in Europe?

Col: No, Heinz Moeller was in Europe. Eric was at the University here in Hobart. And, ah, he was recognised as a world authority on it. And he was getting kicked from pillar to post by the scientific community saying you know, “It’s not there”. How do they know it’s not? They can’t prove no more than we can prove it is there. And short of a dead or alive specimen we’re not going to be able to prove one way or the other, ‘cause photographs will never prove this. You’ve gotta get a freshly dead specimen or a live specimen. And as the Parks and Wildlife here says “Don’t touch it, leave it alone”, if you find a dead one even! “Don’t touch it”, but I tell you what, if I do, it’ll be home in the deep freeze. And we formed a pact, Eric and I - what we were going to do if we found a dead one. Ah, a live one’s a different matter, you just let it go, as I did in ‘95 in the Weld Valley - I let it go. I wouldn’t dare contain it in any way, because the Trappers told me that if you ah got this animal excited, it would drop dead on you. It was a very emotional sort of animal and when they found them in traps, the moment they approached the thing would shiver and put on a tantrum and drop dead. So you had to be very careful with them. And this is what worries me even today, if they find a live one, how are they going to contain it? They don’t know. And there’s so much about this animal we don’t know.

Hanny: Ok, I’m really interested to dig into your stories more - especially your own experiences with the Tasmanian Tiger, but I think maybe to provide some context for those of our audience who haven’t read the book yet and have the same understanding of the Thylacine, can you describe how prolific they were in Tasmania, I guess in the early 1900s?

Col: Oh there were many around as the bounty system proved. That was brought in, in 1888 and by 1900 there were several thousand had been-

Hanny: Several thousand!

Col: There was 2,184 I think officially, but we don’t know that, but I’d say nearer to 3,000 because many were taken on private bounties but didn’t register, and they were paying five Pound per pelt, which was a lot of money when a shepherd’s wage was basically ten Bob a week - ten Shillings a week. And so there was big money in this and the Pearce family at Derwent Bridge and, ah, well Derwent-Clarence River, they trapped something like 70-something Thylacines, and that was a lot of money. And they were just a farming family. So there was money to be made but I don’t think anyone really went out just to trap Thylacines. They were Trappers generally and the Thylacine was an added bonus.

Hanny: Was a bonus.

Col: Yes. And that happened with Churchill - he trapped the last one. He didn’t go out specifically to trap the Thylacine but it bumbled into one of his traps and that’s how he got, he got eight that way.

Hanny: Right. And the bounty was put in place because there was a problem with the early settlers and their animal and livestock being supposedly killed by the Thylacine, but in your book you talked about concerns that this was also to do with the dogs that they brought with that. Is that correct?

Col: Yeah, the feral, feral dogs - dogs that went feral, they brought dogs, ah, domestic dogs and some - a lot of them went feral. And they were adopted by the Aborigines that use them in their hunting and when they - as they got wiped out progressively the dogs became feral, wild, you know, just took off. And great packs of them formed and they did a lot of damage to the sheep - much more than the Tiger. There’s no doubt that the Tiger killed sheep, and we’ve got, now we’ve got people like Bob Paddle who wrote The Last Tasmanian Tiger saying he could only find six instances of sheep being killed by Tigers which is absolute ridiculous nonsense, because, look, I’ve got hundreds upon hundreds of accounts of Tigers killing sheep. And I’ve been told by actual old farmers and Trappers that they definitely did. They definitely were a pest animal. And there was only one way to stop them: wipe them out. Eliminate them. And so that’s basically what happened. But today of course, people are still saying “Parks and Wildlife, well look a Tiger’s killing me sheep”. It’s incredible in this day and age they’re still saying it. And that’s nonsense of course - that’s absolute nonsense today. But back in those days it really did happen, they really did kill sheep.

Hanny: And are there still instances of these feral dogs, I mean dogs of [unclear word] .. there still instances of the feral dogs?

Col: Look, I’ve only heard of one in the last twenty years and that was in the Walls of Jerusalem National Park, and that was about, oh, five or six years ago - there were packs, a pack of wild dogs up there creating problems. But I’m on another book now: The Mystery of the Thylacine and in that I want to explain a lot of this away.

Hanny: Right, yeah.

Col: So there’s quite a story there.

Hanny: So when we talk about like over 3,000 animals potentially being killed - or Thylacine potentially being killed when the bounty was in place, where - was the hunting literally state-wide? Did these kind of Trappers go deep into the South-West wilderness, for example?

Col: No they didn’t, because there were no towns there where you could claim the bounty on. It was a wilderness from, ah, oh, down the Tasman peninsula, and around the bottom there - very few people if anyone lived - and down the West coast, basically no-one lived. It was only Strahan and Queenstown and there was a few little tiny settlements along the coast but there were nowhere, there was nowhere for a Trapper to put his catch. So people didn’t bother to go in there. They [Thylacines] were in there alright. They’re still in there today.

Hanny: So does that help fuel your suspicions about where the Tasmanian Tiger could potentially still exist in Tasmania?

Col: Oh yes! I know where it still ex- I can’t say. It’s there, but I can say in a general area, it’s there. It is, definitely.

Hanny: Alright, and we’re going to get to that. I’m really, I’m really excited to dig more into that. But I guess what I’m also coming to is this concept that there’s a lot of very wild country in Tasmania that it sounds like Trappers didn’t enter and also modern day tourism isn’t entering. It’s just locked up and protected wilderness now. Um, what do you believe is the ideal habitat for the Tasmanian Tiger? Can it still exist in these very wild areas as well?

Col: Look, if you want to see typical habitat - good habitat - go up to Derwent Bridge and look around Derwent Bridge because that’s ideal Thylacine hab- back into the Walls of Jerusalem. But the Tiger just can’t say today “I’m going to live there”, because he’d be knocked off very quickly, so he’s gotta go back, back, back to where he feels safe. There has to be game in these areas, no matter where it is there has to be game, hunting game. And I’ve found parts along the West coast there are - there are plenty of game, and there are button-grass plains where the Tiger could ah, could live there. And so these are the areas that it’s gone back into now to get out of the way, to get away from humanity because it was being killed off.

Hanny: Yeah, because just for our listeners, Derwent Bridge is the southern end of the Overland Track - very famous walking track here in Tasmania. And then the Walls of Jerusalem is becoming an incredibly popular area for especially like families and people entering the hiking market because it’s an easy three night, or even one night, but up to three night overnight walk. But I’ve always thought that as well, that, um, in that area sort of south of the Walls of Jerusalem right through until Lake St. CLair and the Overland Track - that Derwent Bridge area - it’s a lot of lake country, a lot of button-grass lakes. Easy, I guess easy feeding for wallabies which my understanding that the Tiger is one of their preferred food sources, is that correct?

Col: Well it’s not thick bush, and the Tiger, ah, will run it’s prey down and it can’t run its prey down in thick bush. But the bush is fairly open there and sparse, and it can run and hunt there in those areas. And there’s got to be prey for it to hunt, of course, and there are plenty of wallabies in those areas when you get in and have a look around.

Hanny: But what sort of range does one Tiger require to live on, because if we were talking 3,000 in - that we know of, that were trapped in the island of Tasmania, that’s actually quite a large number considering our island is not particularly enormous.

Col: It is when you get out and walk around it! And actually the Tiger wasn’t trapped in the one area - there were many areas, and mainly along the East coast down through the central corridor and the North-West, but very few on the West coast because people just .. go in there.

Hanny: Didn’t go in there.

Col: So when they first arrived here, the central corridor from Launceston to Hobart was much like it is today although a lot of it’s been cleared, but it was sparsely tree country. And that was ideal - there were more Tigers there than anywhere else. But they spread out from there as they started to make inroads into their population. And they had - this animal was supposed to be a dill of a thing, but it doesn’t present itself as a dill to me. It’s got intelligence to get away from humans and that’s what it had to do and it’s done it. And the only reason it survives today is because it had the intelligence to get out of the way and to form its own range in different localities, and it’s range could exist up to fifty-three [sic] kilometres. This is dependent on, ah, the territory, the game and the land itself. It all depends on the nature of the country that it’s living in.

Hanny: Fifty-three kilometres is quite a specific number. How did you arrive at 53?

Col: Fifty kilometres - no, fifty kilometres.

Hanny: Sorry, fifty kilometres, right.

Col: Some have even said eighty, but I say fifty - that’s a pretty good total.

Hanny: And you’ve been establishing just through I guess your own experiences with sightings and, um, coming encounters with the Tasmanian Tiger, plus also other people’s sightings that they work in a corridor fashion as they hunt, is that correct?

Col: Yep.

Hanny: And can you explain that a little bit more for us then?

Col: Well, it doesn’t hunt willy-nilly over a vast area, but it’s got definite paths that it traverses. He knows where the game are and it will form a - what I call a corridor - to get from one point to the other, and it’s not a narrow corridor a hundred yards wide. It could be a kilometre wide. But it’s a general path and a direction through the, the territory. It doesn’t go from - you know, all over the place, so it, and it will work its way around there, in a period of, oh, five or six weeks. And it will come back again through that area and then - this is how I work my logic, that, if you want to ah, get near a Tiger, you have to find where it’s been through and be back there, you know, within a month or six weeks.

Hanny: Yeah, right, ok.

Col: And I smelt one, by following this, ah - I got near enough to smell the thing and ah, in the Sawback Range, out from Adamsfield.

Hanny: Ok, so down in the South-West area again. So the, um, the corridor theory - which sounds completely justified to me - it’s generally following areas where the Tiger can move more easily in the terrain, so say, like, button-grass plains and open, more open vegetation strips..

Col: Where the game is, yeah.

Hanny: And then it basically roams every five to six weeks around a set corridor because it disturbs the animals as it moves through the first time, is that correct?

Col: Well they get disturbed if they’ve seen a Tiger, yes. But it knows where the game goes - the trail the game uses, and that’s where it bases its corridor on.

Hanny: Right.

Col: But there are summer and winter ideas here because in the colder weather the game moves down from the higher country and when the warmer weather comes it moves back up. So the Tiger will be conversant with this and it will adapt its range accordingly. That’s what I believe, anyway.

Hanny: So, what sort of habitat does the Tiger actually sort of reside in, say in bad weather situations or when it’s sleeping? You talked a lot about caves and hollow logs and things in the book. So can you describe a little bit more about the setting in which that-

Col: Well it hides up during the day, in natural hides. And this could be a cave, of course, or a rock overhang. It could be a bank of man ferns. It could be a hollow log. I’ve found many places that it could hide up. So it wants to get away during the day and that’s when it sleeps it off, and then at dusk, between dusk and dawn are the times that it emerges and hunts. And so, I think probably the best time, if you want to really find a Tiger is to be around dawn, when it comes back from the hunt. And that’s when I seen the Tiger in '95. It was coming back from its hunt.

Hanny: Can we talk about that time? Can you take us back to then? What was the day like? Where were you? Can you set the scene for us a little bit?

Col: Well I was told of a section of the Weld Valley alongside a river called the Snake River, which is way out under Mount Anne. And there were no logging trails there - they log the other side of the Weld River. Now the Weld River runs from under Mount Bueller, and it runs through to the Huon. And it runs through some of the most inaccessible country you could ever imagine. And this old fellow, Bert Brooks, he told me that he knew there were Tigers back in there, and that was in ‘93, so for the next two years I tried to get in and the bush beat me. I went through from the - under Mount Bueller and followed the Weld back, and the Weld goes through a lot of different types of forest, and some of it’s almost impenetrable. So there were various trails that run, that ran from the pylon - the electricity, ah, line, that goes through alongside, ah, Mueller Road, ah, that runs from the Styx Road and it runs through back to Clear Hill Road - it runs through the bush there. And I followed these and tried to get through that way and wherever I went I was beaten back by the bush.

Hanny: So by cutting grass?

Col: Oh, there’s everything in there. A lot of stuff, you can imagine, it’s there, and horizontal [scrub], ah, probably one of the worst things you can strike. And every time I got to the river on the northern side, ah, it was flooded. I couldn’t cross it to the other side. So eventually in early ‘95 I worked out a plan to go down the Clear Hill Road and I branched off from the South Coast Road - or the Gordon River Road and I went back under Mount Anne. I walked through to the Weld River and followed it through to the Snake. It took a couple of days - pretty rough country through there - but eventually I, I wondered why no-one else had been through there before. Then I could see why. It just was, you know, that sort of country you wouldn’t bother about and a lot of it floods when there’s a lot of rain. It floods the plains there that flood. There’s only one, two rivers through there, but are a lot of little streams and the whole place floods. And it snows - you get snow a foot deep through there, and so, I struck in, in early March and I was lucky to get through, get in there. And I camped alongside the Snake River this night and during the early hours of the following morning I heard these yips, high pitched yips, like Terrier dogs up ahead, in the button-grass plains up ahead. And I thought well, what are dogs doing out here? And, it all came back what the old Bushies had told me - they sound like high pitched yip, like a Fox Terrier dog, and I heard these yips coming, and I wondered what it was and I wasn’t sure. But the next morning, I packed up at just on daybreak, and I got my pack all packed up … and so everything was packed up on the pack, [unclear word] everything was there. And I thought well I’ll have a quiet look around, as I usually do before I break camp, and I walked around. And I was standing there quietly and out of the ferns this animal came out and shot straight back in - it seen me, apparently … So I packed up and everything was ready to go. This dog shot out of the ferns - well I thought it was a brown Cattle Dog, and shot straight back in again. And I was only, maybe, ten, twelve feet from it. It wasn’t very far. And when it went into the ferns I walked to the edge of the ferns where it had gone and called it up: “Hey, boy, come and give us a pat”. I thought it was a dog. If it had have been a dog I would have taken it home with me, ‘cause wallaby hunters lose their dogs … And when it went into the ferns, I followed it in and, ah, maybe for 20 or 30 yards and I could see the ferns moving ahead of me and I knew that it was keeping away from me. And I stopped and called it up again. And it went on to a - it moved onto a wombat trail [that] was semi-cleared and I could see it more clearly and then suddenly it stopped and it half turned and glared back at me. And that’s when I, my eyes ran down its back and I seen the stripes and the tail. And the penny dropped and I went into shock, because once I realised what it was - there was no doubting what it was - that’s when the penny dropped and I, I just ah, went into, basically into shock. I couldn’t move, I just - my feet felt glued to the - it’s a funny feeling when you can’t move your legs, you feel glued to the spot. And this thing stood there, eyeing me off! And I could see these great big, black, featureless eyes and I thought oh, what’s it going to do? Anyway, then it started to back-track and it turned right around and faced me head-on. And that’s - I had no doubts then what it was, and it gave a big hiss and I thought hello, it’s going to have a go at me. And this all happened over a 20-30 second time-frame I suppose, and it wasn’t any further than probably, well, 20 feet away from me. It was near enough to get a good look at. And, ah, I thought well what’s gonna happen here? Because I was in no condition to do anything. I just stood there and looked at it, and it glared at me. And then it started to do its back-track again and backed off and went into the ferns and I lost sight of it, and I could see it moving around, moving away, and I thought I’ll follow it. So I went back to my pack and I thought now what am I going to do if I catch up with it? What’s going to happen? And I thought, well, I don’t really want to catch it. I’ve seen it. Perhaps that’s enough. And so I sat down and had a really strong up of coffee to settle my nerves ‘cause I was shaking like a leaf. Anyway, when I finished that I thought well maybe I’ll see where it went. But of course, when I went to see where it went, it could have gone anywhere, it doesn’t [unclear words]. I thought, well it’s a waste of time. And that’s when I started to take account of the situation. I’d seen it. I’ve no doubt what it was. What was I going to do about it? And during the long walk home I - many things went through my mind. That's when I formed this pact to tell no-one. Keep it to myself. Ah, I was scared what might happen if the wrong people found out, got in there. And, the thing about I didn't tell my wife - if she could have let it slip to someone, you know, it's not that she probably would, but you never know. It's just one of those things that I wanted to keep to myself. Now I've found other people in exactly the same position who say they've seen it but they didn't want to tell anyone at the time and maybe five years later they tell me. And so it does happen. The same has happened to me.

Hanny: How have you become that sort of go-to person? Do you think it's through writing of the books, or is it - it's in your nature that you're a very approachable person, because how many sightings have you had reported to you from other outside sources, other than your own?

Col: Ha! Oh, I haven't counted them up but there'd be, probably hundreds, over the years. This is going over fifty years. I've had a lot, a lot of sightings. And, ah, some of them I wouldn't believe. Some of them I would believe.

Hanny: Have the sighting numbers increased recently?

Col: No.

Hanny: And have you noticed any changes since you released your book?

Col: Oh it's dropped off. Not so much since I released the book - that was only a few years ago - but in the last twenty years they've dropped away. I used to get maybe 30, 40 a year, back in the '80s, '90s, but now they've dropped away and I might get five or six. But what I am getting are fairly good ones, and most of the good ones come from the road between Derwent Bridge and Queenstown, along that stretch of road. And that's where the good ones come from.

Hanny: You mentioned one particular one in your book, where someone was driving - was it dawn, I think - and a Tiger crossed the road in front of him, and he stopped but the Tiger just disappeared down in the -

Col: Yep, into the morass below.

Hanny: Into the morass.

Col: Yeah.

Hanny: Yeah. I actually, personally believe that my partner and I saw a Tiger around the Mole Creek area. We were driving at midnight up into the start of the Walls of Jerusalem trail and, um, we'd left work very late after work and thought that we would do that drive at night and we were going very slowly because obviously there's a lot of animals on the road in that area and this animal - again, long, dog-like, but wasn't running like a dog or moving like a dog, crossed in front of the car, and this is before I read your book. Way before. And we both sort of looked at one another and was like "Did you see that?" You know, "What was that?" And I think the more that I, um - since we started stocking the book in our store because I believe I want more and more people to read, and the more times that I point out about your book, the more people kind of open up to me and go "Oh yeah, you know, we believe we've seen one" and you know, "My friend saw one", and the other day I had a copy of the book right on my counter and I had a little note on it saying, you know, you've got to read this, it's a great gift as well, um, for anyone that you know who loves Tasmania. And this woman said to me as she was doing her payment at the checkout, she said "Oh, my friend's seen one." I said "Oh, really?", you know, "Where? Where did she see it?" And she said "Oh, I actually can't tell you", um, "it's with lawyers at the moment". So obviously, um, this friend -

Col: I think I know the one you mean. They took one on a remote camera, is that the one?

Hanny: Potentially. She couldn't tell me anything.

Col: Down in the Florentine.

Hanny: Yeah, right.

Col: I think I know the one.

Hanny: Do you-

Col: Could be.

Hanny: Um, legitimate? Possibly?

Col: What's that?

Hanny: Do you believe that it could be a legitimate -

Col: I've seen this bit of footage.

Hanny: Yeah, right.

Col: [Unclear words] I think it's the one you're talking - and I think it was a big Tiger Quoll.

Hanny: Oh, ok.

Col: Ah, but, um, anyway, if that's the one I'm thinking of, ah, the fellow is supposed to have sent it to England for a verdict from, an expert. Now, look, let's get one thing - if I may, at this stage - there are no experts when it comes to the Tasmanian Tiger. Now, I think you'd have to agree that an expert on anything is someone who knows everything there is to know about the subject.

Hanny: Yeah.

Col: No holds barred. And this animal, there is so much that we don't know about it. We an assume, or guess, and that. Even Eric Guiler said there was so much that he didn't know about it and he was the world expert [unclear word], basically the world expert. When people call me an expert I cringe, because I'm not an expert - there are no experts alive today. The true experts were the old Trappers and Bushmen who knew the animal, who worked alongside of it, and they knew its moods, what it got up to, how to even catch it, and some cases. But today there - we don't know hardly anything about it. What we can - maybe, guess we do, and there is so many people around that jump on this word "expert" and fellahs fluff up and they thing "Oh, I'm an expert" but they're only kidding themselves. There are no experts. And so -

Hanny: It all happened so early in the, you know, in the 1900s that we didn't, we don't have the knowledge even that, we have now or the technology or anything, so.

Col: Well look, I spoke to Elias Churchill and several other fellahs that hunted them, that actually knew them. They were the experts. They know what they were talking about. But now you get a scientist who jumps on the bandwagon and says "Oh, I'm an expert" but they're not experts at all. And we've got, even one particular who said this animal couldn't kill anything bigger than a possum because its jaws are so weak - it's absolute ridiculous! This thing could bring down a sheep. Ah, a sheep was equivalent to the size of the Thylacine. The sheep that came out here in those earlier days weren't quite as big as the sheep today. They were more in comparison with the size of a Thylacine, and, ah, it could certainly bring them down. But, ah, now we got a certain scientist - I won't mention names - saying "Oh, no, their jaws are so weak", ah, "We found out by analysing this Thylacine head" - that, they've got the head, and the jaws are so weak they couldn't bring anything down, anything bigger than a possum. It's absolute nonsense. So you've got all the scientific community getting up and imagining all these marvellous things that the Thylacine could or couldn't do. They don't really know. And until we can get one and study it closely - a live one - then we're not going to know.

Hanny: Yeah. I sit on the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council, which is a select group of people from the community who advise on behalf of the general public, to the heads of National Park[s] and one of the gentlemen - I won't mention names, but he is an incredibly well known, um, slightly older gentleman who works within the science community here in Tasmania; he's won Awards of Australia medals, I think - he really is an amazing person, and I, um, sort of poked him with my elbow the other day and said "Guess who I'm going to be talking to?" And I told him that I was going to be talking to you about the Thylacine on this podcast, and he said to me "Yeah, I've seen them, or had experiences four times". And this is someone that I respect endlessly, his knowledge. So we're not just talking about sightings coming from tourists driving their hire cars over the West Coast road. We're talking about scientists who've been out on epeditions and actually have had their own encounters. So, I guess, kind of going forward, um, what would happen if we were to have a sighting that we can prove the Tasmanian Tiger existed? What do you think would happen if that -

Col: Well look, the Government is fearful of this. Um, and, um, there are people within Government, and within Parks and Wildlife who know - they know it's there. Of course they do. They know the Tiger exists. But mainly because of the logging industry - they want to protect the logging because it's a very big thing in this state, logging. And if the Tiger was proven to be in an area then the Greens would jump up and down and scream blue murder and want the whole state locked up, and that's what they're scared of. And so this - although they know the Tiger is there, they don't want it to release to the general public because they know the outcome, what the outcome will be. So there are certain people within Government, and within the Parks and Wildlife, they know well it's there but they shut their mouths and say nothing. And until it's proven to be there they won't say a thing because they don't want the general public to know it. Because they're fearful of what's going to happen if it's proven to be there. So, I've heard of them being shot, er, in the last 20 years, and other people have heard of it too.

Hanny: Wow.

Col: And hastily disposed of. I've heard of them being run over on the roads and hastily got rid of, and so, these things do happen, but, we're being kept in the dark about it for, mainly for the reason, I think, for the logging - because that is a very important and viable part of the state, so many people imagine, and if you lost that, we would lose a lot. And so there are certain people who know, and, er, but I'm not a scientist and I'm not in the Government, so I can say what I like and they can't do anything to me. I mean I'm entitled to say what I believe. But if I was in the Government I'd be told to shut my mouth. And because I've spoken to certain Government Ministers about this, and they believe it's there. And they're out of Government now, they're gone. But, some years ago. So, you know, it's a general -

Hanny: Obviously needing to come to some conclusion in our discussion today, but, you mentioned Forestry. There is a bit of a belief amongst those of us who do believe, that Forestry, farming and hydro potentially could have impacted the ability for the Thylacine to still exist.

Col: Yep.

Hanny: Do you think there's enough terrain left in Tasmania where we can have a viable breeding population, or are the animals that we're seeing potentially older ones? Do we know how long the Thylacine actually can last for?

Col: Well maybe it's got a lifespan of 10 years in the wild.

Hanny: Right. So similar to a Devil?

Col: Well the Devil's only got 5 or 6 years. But, um, the Devil is considered the apex carnivore now, but the Tiger really still is, but of course it's not recognised, as such. Um, look, that's a curly one really. It's a very difficult one to say. There's no proof of anything at the moment, and so I guess you can't really say yes or no to the question.

Hanny: If - so, I guess to start concluding, you've written the book to help share your knowledge in the hope that some of us who read it will potentially continue the legacy, is that correct? Continue the, um - not "fight", but "search" to preserve the Tasmanian Tiger's habitat and potentially therefore the existence of the Tasmanian Tiger, am I correct in saying that, to some degree?

Col: Well, most people would want to protect it. I think there's only a very small percentage that would want to shoot it, or harm it. So most people, if they knew it was there, they would be happy just to know that - if it could be proven to be there, but of course it hasn't been proven to be there. And all the photographs in the world won't prove this because they can be so easily rigged and manipulated. So a live or a dead one is the only way, and I'd much rather find a freshly dead one in the bush than a live one, because then that would prove once and for all. With a live one you, well, you're not allowed to contain it, so the law tells us, or touch it or harm it in any way so, you just gotta look at it and let it go, much like I did. And, well, but a dead specimen, that would prove beyond doubt - a freshly dead one.

Hanny: Any obviously roadkill is always sadly a potential here in Tasmania. I, um - one of the stories that blew me away in the book was actually, um, the cycle tourists on Elephant Pass over on the East Coast, coming down past the famous Elephant Pass Pancake Parlour. It's an area which has relatively dense farming and housing situation in amongst open and dense bushland, depending on where you are in that area, and they came across some roadkill that at the time they couldn't identify. They then went to visit the museum here in Hobart,

Col: That's right.

Hanny: And saw the tiger and just kind of randomly said "Oh, that's what we, that's what we think we saw as roadkill". The museum curator gave them a bit of a telling off and said that couldn't be possible, and then they bumped into you out at Mount Field when you were giving a talk. What do you think that animal was? Could that potentially have been a Tiger at Elephant Pass?

Col: Oh, well the way they described it, it definitely was, but, as they said, the front half was smashed and the back half had stripes on it, a long, stiff tail, and the way they described it, there's no doubt and I've got no reason not to believe them. People say "Well why doesn't the Tiger get hit on the road?" Because the Tiger doesn't eat carrion, is the simple answer to that. The Devil will go onto the road deliberately to eat a dead animal. The Tiger didn't do that. The Tiger never ate carrion, it only ever ate what it killed, itself. The old Trappers were adamant on this, and they didn't touch poisoned meat. So, ah, very unlikely they were poisoned. So, um, this is probably the main explanation of why they don't get killed on roads, because - they cross the road, but they never stop to eat carrion on the road and that's when animals get killed. This is the Devil.

Hanny: Yeah. And then that makes sense. So what would be your message to us as Tasmanians, as listeners to this podcast further afield, um, going forward? Do you have a message for u?

Col: Well if you're out in the bush and you're fortunate enough to see a Tasmanian Tiger, or Thylacine, leave it alone. Look at it. Get your photo if you're lucky enough to try, but don't go near it. Leave it alone, let it go its way. And don't tell the media. Keep it to yourself, and perhaps to your friends but let a bit of time pass between when you've seen it and when you let it out. Maybe a year or two. And I know it's a hard thing to do for some people - they can't, ah, wait to tell everyone. But the worst thing you can do is go to the media, because they sensationalise it so much, and build it up to something that it really isn't. And a lot of it is nonsense they put in there anyway, but, it's happened before and the moment they get hold of it, it's on, you know - like the things that happening in South Australia at the momnet. And I know that - [the fellah?] this, um, pushing all this, these things over there and, and he's out to make a bit of a name for himself. He likes publicity. And it makes good newspaper stuff, but I'd say leave it. Leave it. Leave it go, leave it be. Consider yourself really, really fortunate you've been lucky enough to see it, but don't try and harm the animal in any way. Just let it go and forget about it for a while. I know it's easy to say.

Hanny: (laughs) .. for 17 years and then write a book!

Col: Be very, very thankful that you've seen it and happy that it's still there.

Hanny: Are you happy for us, if we were to have our own experiences, to continue to write to you?

Col: As long as I'm here, yes.

Hanny: And what - what is your greatest fear? I mean you obviously can say yes or no.

Col: That officialdom get hold of this and ruin it. The Government has ruined many things that they've got hold of and taken over. Absolutely ruined them. And this is one animal they could ruin because so little is known about it and the - as I say, the so-called experts will come into it, and I can imagine this, and then they'll say "Oh, well we'll do this and we'll do that" and, ah, they may kill the thing off very quickly. And we've got Mike Archer who wants to clone it. He wants to, you know, not clone it, he wants to -

Hanny: Re-create it.

Col: Re-create it, yeah. I know Mike well and I've said to him "Mike, this is ahead of its time. It may - it may happen in 50 years time, but just at the moment.. What are you going to do when you find it?" He said "Oh, we'll let it in the bush", but here you've got an animal who doesn't know even how to look after itself in the bush, and then if someone doesn't come along and shoot it, it'll die of starvation beause it's lost the ability to hunt, so there's no easy ques- no easy answer to this question, but, um, if it is still out there, and I believe it is, it's hanging on, then it's done [so] through its own initiative and, ah, you know, why, why, ah -

Hanny: Why mess with that?

Col: Why mess a good thing up? Let it go.

Hanny: Nature is a very amazing thing - way smarter than I think we are, I mean, I loved - I used to work as a hiking guide at Maria Island and there's a story about when the island was created that we had sadly another animal that was extinct in Tasmania called the Tasmanian Pygmy Emu - like really, really small, almost the size of a chicken.

Col: Yes.

Hanny: When the island was created as a National Park, someone - I don't know who it was - thought that it would be, um, the opportunity to bring - or to try and re-create the pygmy emu. So they went to the mainland and they found the smallest of the large mainland emus and popped them on this island off the east coast of Tamania where, all to - left all to themselves, they blossomed and turned into these ginormous mainland emus that ended up being culled because they caused so many problems!

Col: Was that Maria Island, was it?

Hanny: Maria Island, so, I think nature can outwit us in many ways, but um, yeah. Look, today was only a snapshot of your knowledge, your experiences out in the wild and with the Tasmanian Thylacine. I can't encourage people enough to read your books. I can't wait to read Lure of the Thylacine, which is your newer book, recently released, and then you mentioned you're writing another book at the moment. Can you tell us a tiny bit more about that book?

Col: Well it's the Mystery of the Thylacine. There's a huge mystery surrounds this animal right from the very earliest days to the present, and I want to try and, um, get hold of it a bit and explain it. And it's not an easy book to write, providing I live long enough to finish it. It, ah, people are onto me already, you know, "When is it going to be finished?" but, it's not that simple when you're writing a book of this nature. You've got so much research to do, and I've been researching for over 12 months now and I'm, I'm nowhere. I'm still getting, you know, looking into - getting ideas and stuff, so, I know the direction I want it to follow is ah, to try and reveal the mystery. And it is a mystery. Ah, even today, um, it's as big a mystery as it ever was. And will it ever be solved? But yeah, anyway. It's going to be something a little bit different to the last two books. And, ah, so -

Hanny: Well Col, I - on behalf, I hope, of the Tasmanian public and the broader audience listening to this podcast, I want to thank you. I want to thank you for sharing your knowledge, your beautiful way of writing which inspires me as I sort of dream about writing a book one day. I want to thank you for your humility and humbleness because it speaks very loudly. I learnt (?) something that I really respect. I want to thank you for taking the time today to talk with us on our podcast, because I really hope that your message is shared and spread and that together we can help to preserve what we hope is the Thylacine living here in Tasmania today.

Col: Thank you Hanny.

Hanny: Thank you Col.