Prospective Tasmanian Tiger tracks found in Tasmania

Following publication of this article, a number of people have contributed additional material relating to the walking gait and tracks left by Tasmanian Devils. In short, the Tasmanian Devil can be seen to place its hind foot forward of where its front foot was placed. This means according to all measures considered below, an explanation of Tasmanian Devil is equally as likely as Tasmanian Tiger. Given the lack of definitive evidence of the persistence of the Tasmanian Tiger, the conclusion must be that more likely than not, these tracks were left by a Tasmanian Devil. The analysis has led to a number of important realisations regarding the tracking of Tasmanian Devils and Thylacines, with implications for tracking all species. In due course a new article will re-visit and summarise the insights gleaned below, together with the information gained from the newly submitted materials. When that article is complete, this article will be updated to announce it. (This note added 6 Nov 2019).

Media enquiries regarding access to all 10 high resolution photographs are directed to the contact form at www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au.

Abstract

During a focused search for evidence of the persistence of the Tasmanian Tiger in Tasmania (Thylacinus cynocephalus, also known as Thylacine), a sequence of quadrupedal animal tracks was discovered and documented through high resolution photography. There are twenty marks in the sequence, interpreted as consisting of two overprints - meaning a hind foot has stepped onto the corresponding forefoot's print - and eighteen individual footprints. Distinguishing Tasmanian Tiger prints from those of the Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) is a difficult process when only individual prints are available for assessment. These two species, however, have readily distinguished footprint patterns: the placement of the hind foot on the ground relative to where the corresponding forefoot was placed is unique to each species. Therefore in cases where the individual prints are of sufficient clarity to discern forefoot from hind foot, and where there is a sufficient number of prints arranged in a continuous track line in order to discern relative placement of fore and hind feet, these two species may be distinguished by footprint pattern. The eighteen individual prints documented are arranged in a continuous track line consisting of forefoot / hind foot pairs. Of these nine pairs, eight are documented through high resolution photography sufficient to discern the relative placement of fore and hind foot within each pair. Of these eight pairs, seven pairs are arranged in a layout expected for Tasmanian Tiger, and one pair has the foot placement reversed, ie. in the layout expected of the Tasmanian Devil. This author concludes that on balance of probability, within the scope of current knowledge on Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil tracks, this track line was more likely created by a Tasmanian Tiger than a Tasmanian Devil. Additional research into Tasmanian Devil walking gait patterns has the capacity to strengthen this conclusion, or to invalidate it.

Preface

In publishing this article a conscious decision has been made to withhold the location at which the track line was observed, beyond stating it was located in Tasmania. The rationale for this follows "A decision tree for assessing the risks and benefits of publishing biodiversity data" (Tulloch et. al, 2018) and is given in Appendix 1. For the same reasons, the precise date is withheld, except to say the track line was observed between 2008 and 2019.

Introduction

The Tasmanian Tiger - also known as the Thylacine - (Thylacinus cynocephalus) is listed as extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Burbidge & Woinarski, 2016) and by the Australian Government (Department of the Environment, 2019). Its former range included New Guinea and mainland Australia but in modern times it was known only from the Australian island state of Tasmania (Burbidge & Woinarski, 2016). The last captive Thylacine died in a zoo in that state's capital, Hobart, on 7 September 1936 (Department of the Environment, 2019). Many notable searches have subsequently been conducted, expending considerable effort, without yielding a specimen (eg. 1937, 1945, 1959, 1963, 1968, 1980, 1982-3, 1984, 1988-93; Parks and Wildlife Service Tasmania, undated). Many amateur researchers, including this author, have also searched without yielding a specimen.

Some of these searches collected circumstantial evidence (eg. "definite footprints" described by Rosemary Fleay-Thomson regarding the 1945 expedition conducted by her father, David Fleay (Campbell, undated A)) and in 1984, Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Officer, Nick Mooney, reported the species as extant, saying "The recent sighting [and four other reports] confirms that the search area was used by thylacines at least irregularly up until Autumn 1982" (Mooney, 1984). Despite this, the species was declared extinct just two years later - fifty years after the death of the last captive specimen (Parks and Wildlife Service Tasmania, undated).

The Thylacine first became a subject of serious interest for this author in 2006 (Rehberg, undated A) in response to a tourist's claim to have photographed one in Tasmania the year before (Bailey, 2006). Initial interest was concerned with "examining the evidence" (Rehberg, undated B) for the Thylacine's persistence that others put forward in the form of personal testimony regarding possible Thylacine encounters and photographic and video evidence. However in 2008 US television show Monster Quest funded an expedition to Tasmania (Rehberg, undated C) in which this author, with a colleague, conducted a number of hikes into remote wilderness in search of evidence for the persistence of the Thylacine. Since this time, this author has continued conducting self-funded expeditions in Tasmania in search of evidence for the persistence of the Thylacine (Rehberg, undated D). It is during one of these expeditions that the sequence of footprints was discovered that is the subject of this discussion.

Summary of key points

- An animal track line was discovered in Tasmania.

- It consists of 20 marks in a thin, smooth layer of mud.

- Two marks are interpreted as "overprints"; eighteen as individual footprints.

- The footprints are pristine, clear and fresh.

- The size of individual footprints is consistent with either an adult Tasmanian Devil or sub-adult Tasmanian Tiger.

- The shape and appearance of individual footprints are consistent with either Tasmanian Devil or Tasmanian Tiger.

- The footprint pattern exhibited in the track line is consistent with Tasmanian Tiger and not consistent with Tasmanian Devil.

- As a result, within the context of our present understanding of Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil tracks, the track line best matches that expected of a Tasmanian Tiger.

- It is recommended a further study be conducted which analyses Tasmanian Devil footprint patterns. The results of such a study have the capacity to either strengthen, or negate, this conclusion.

The footprints

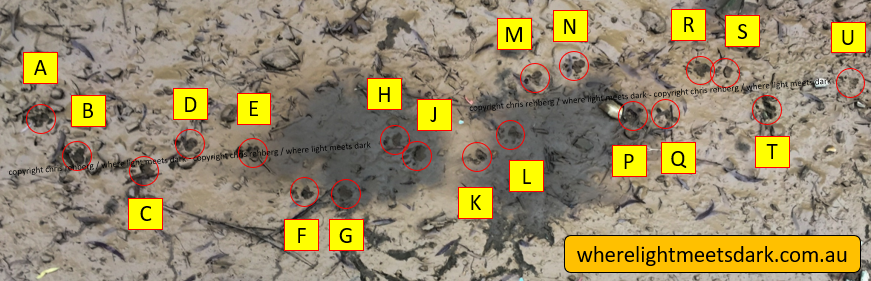

The track line that was discovered consists of 20 marks: two overprints and eighteen individual footprints. Each mark has been designated a letter as a convenient means by which to identify each mark in discussion. A selection of images depicting the footprints that were found is presented here. Note: a majority of the high resolution images has been retained by the author.

Example of quality

The footprints in question were discovered in a thin, smooth layer of mud. Its moisture content was such that the footprint impressions formed were of exceptionally pristine quality. The prints exhibited no apparent effects of weathering.

Individual footprints R and S showing forefoot ahead of hind foot. Copyright: Chris Rehberg / Where Light Meets Dark.

The photograph above depicts two separate footprints, which have been labelled "R" and "S". The print labelled "R", being the larger print, shows a forefoot. Print "S" shows a hind foot. It is clear from the full track line (described below) that these two prints come from the right hand side of the animal.

Details of note visible in this photograph include:

- The surface texture of the skin is readily apparent in large portions of both prints.

- The forefoot shows some slippage at the rear of the carpal (forefoot) pad and at the rear of some digits.

- The hind foot's plantar pad shows an overall ovoid shape, but the anterior edge reveals a deeper indentation having multiple lobes.

- Three of the four obvious forefoot digits exhibit claw marks.

- There is a suggestion of a fifth digit impression where the "thumb" would be expected for a right forefoot - between the carpal pad and the rule.

- Major marks on the rule are 1cm apart; minor marks are 1mm apart.

- There is the stem of a leaf protruding from the mud between the two prints.

- Cracking in the mud is evident, consistent with a drying of the mud.

- The forefoot's 5th digit (counting from thumb) overlays one of these cracks and appears to have compressed the crack - this is consistent with the print being made after the mud cracking. Given the pristine quality of the print, and that it is reasonable to expect the mud to take considerable time to dry to the point of cracking, these features are consistent with the prints being very recently made (ie. prior to being photographed).

- To the hind foot's right and rear are stones beneath the mud - these may be discerned by the change in colour tone of the mud, which is indicative of daylight reflecting off the mud surface at different angles.

- This interpretation of the pattern of light and shade reveals that there are smaller stones and pebbles beneath the mud in other places in this photograph - indeed, examining all of the prints reveals a stony surface beneath the mud for most of the track line; it is this hard surface beneath a relatively thin layer of significantly dried mud that has been key in producing the high quality of the prints seen here.

Additional pair of prints showing reversed footsteps

A key element in the interpretation of these tracks relates to the placement of each hind foot, relative to the placement of the forefoot on the same side of the body.

Individual footprints H and J showing hind foot ahead of forefoot. Copyright: Chris Rehberg / Where Light Meets Dark.

The photograph above depicts a further pair of footprints from the track line. In contrast with the earlier photo (showing footprints R and S), the relative position of hind and forefoot is reversed. In this photo the hind foot has been placed ahead of the corresponding forefoot. The significance of foot placement is discussed more fully below.

Other details of note visible in this photograph include:

- The obvious smooth texture to the mud, again.

- The pristine clarity of the prints whereby the skin texture is again readily apparent in both prints.

- The presence of claw marks on the hind foot this time.

- Claw marks are also present on the forefoot.

- The lack of any apparent "thumb" impression by the forefoot (print J).

- A leaf is present in the mud again, between the two prints.

- Stones are apparent submerged beneath the mud again.

- The mud exhibits the same cracking as described before - most noticeable near the stone at the upper edge of the frame.

- Major marks on the rule are 1cm apart; minor marks are 1mm apart.

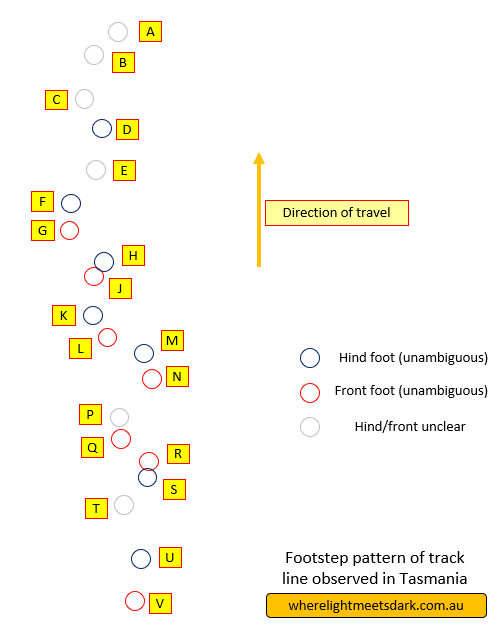

The full track line

Two context photographs showing almost the entire track line were taken. One context photograph includes 19 of the 20 marks and the other shows fewer.

Near-complete track line showing 19 of 20 marks found. Copyright: Chris Rehberg / Where Light Meets Dark.

Summary table

The table below provides a summary of interpretation of each mark (including the 20th mark, not shown in the context photograph).

The columns represent:

- # = mark number

- Name = mark name (label) (The letters 'O' and 'I' are omitted to avoid confusion with the numerals 0 and 1)

- In Main = whether the mark is visible in this context photo (Y = yes / N = no)

- Hi Res = number of high resolution photos taken of this mark

- L/R = whether the mark represents a left foot (L) or right foot (R)

- F/H = whether the mark represents a front foot (F) or hind foot (H)

- Pair = the two marks (by name) consisting a pair of feet (front/hind) from the same side of the body

- Matches = species matching the pair configuration (Thylacine = hind foot placed ahead of front foot; Devil = hind foot placed behind front foot)

| # | Name | In Main | Hi Res | L/R | F/H | Pair | Matches | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | Y | 0 | R | A-B? | If A-B is a pair then C is an overprint. | ||

| 2 | B | Y | 0 | R? / L? | A-B? / B-C? | Thylacine (if BC) | If A-B is a pair then C is an overprint. | |

| 3 | C | Y | 1 | L | F | B-C? | Overprint? Appears to show forefoot. | |

| 4 | D | Y | 1 | R | H | D-E? | Thylacine | If D-E is a pair then C is an overprint. |

| 5 | E | Y | 1 | R | ? | D-E? | If D-E is a pair then C is an overprint. | |

| 6 | F | Y | 2 | L | H | F-G | Thylacine | |

| 7 | G | Y | 2 | L | F | F-G | ||

| 8 | H | Y | 1 | R | H | H-J | Thylacine | |

| 9 | J | Y | 1 | R | F | H-J | ||

| 10 | K | Y | 1 | L | H | K-L | Thylacine | |

| 11 | L | Y | 1 | L | F | K-L | ||

| 12 | M | Y | 1 | R | H | M-N | Thylacine | |

| 13 | N | Y | 1 | R | F | M-N | ||

| 14 | P | Y | 1 | L | P-Q | Thylacine | ||

| 15 | Q | Y | 1 | L | F | P-Q | ||

| 16 | R | Y | 1 | R | F | R-S | Devil | |

| 17 | S | Y | 2 | R | H | R-S | One high res photo shows print only partially. | |

| 18 | T | Y | 1 | L | Forefoot or overprint. | |||

| 19 | U | Y | 1 | R | H | U-V | Thylacine | |

| 20 | V | N | 1 | R | F | U-V |

Notes on summary table

Various prints are clearly paired by virtue of being in close proximity to one another, viz: F-G; H-J; K-L; M-N; P-Q; R-S.

Other prints are further spaced apart. In particular the spacing between prints A through E make pairing any of these prints more difficult. The interpretation given above is that A and B may form a pair, and D and E may form a pair, leaving C as an unpaired overprint. The rationale for this interpretation is that prints D and E generally lie on the right hand side of the track line, in the direction of travel - and this is evident on inspection of the other prints.

It is conceivable, however, that B and C form a pair, and that A is isolated - either an overprint, or its pair is not within the frame of the photograph. While it can be seen from the high resolution photograph (not shown here) that C is a forefoot, unfortunately no high resolution photograph was taken of prints A or B - making identification of those as fore or hind feet difficult. However, if B and C do form a pair, then by inference, B is a hind foot (as C is clearly seen to be a forefoot) and in this case the configuration of hind foot ahead of forefoot would suggest the pair B-C best matches Thylacine also.

With pair D and E however, print E is not clearly identifiable as fore or hind foot but D is identifiable as a hind foot. This implies E should be a forefoot and this configuration (D-E) again best matches Thylacine.

Likewise, for the P-Q pair, the footprint P is not discernible as either fore or hind foot, primarily because it has partially been made on a stone. Footprint Q is clearly a forefoot, however, inferring P is a hind foot and the P-Q pair also best matches Thylacine.

The mark labelled T appears to be an overprint and is not recognisable as either a fore or hind foot.

The mark named V is not visible in the context shot but is visible in a high resolution photo showing marks U and V together.

The labels "O" and "I" have been omitted intentionally (to avoid confusion with the numerals 0 and 1).

Seven of the eight pairs having high resolution photographs of both prints, have configurations best matching Thylacine. One pair has a configuration best matching Devil.

Discussion

Eric Guiler notes "the footprints of thylacines are of prime importance in any evaluation of field evidence for the presence, or otherwise, of the species" (Guiler 1985). He continues that "the features to be examined in any spoor are the size of the pad and its shape, the number of toes and the shape and size of the toe pads, the number of claws and their size and whether they appear in a spoor, the spacing between the toe pads as well as the foot pads, and finally the distance between each step and the nature of the gait" (pp 43-5). In this section, each of these features is evaluated for the track line that was discovered.

Print size and stride length

Although Guiler states "there are two species whose spoor can be confused with that of the thylacine" and "these are the wombat and the dog", this author contends that a further real candidate for confusion is the Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii). In citing the Wombat (Vombatus ursinus) and Dog (Canis lupus) it would appear Guiler is primarily concerned with the footprints of an adult Tasmanian Tiger, which would be large. In this case, Dogs and Wombats can produce prints of comparable size. Additional and specific details reported by Guiler relate only to adult Thylacines, including that "the distance between each subsequent print of any one foot in an adult thylacine should be about 80cm or more" and that "in general, a print larger than 4.5 cm in width is likely to be that of a wombat, a dog, or a thylacine" (Guiler 1985, pp 45-7).

Utilising the rule included in the photograph of prints R and S, the broadest width of the forefoot (print R) is calculated to be approximately 2.6 centimetres. This is considerably smaller than the adult size quoted by Guiler and clearly if the track line was made by a Tasmanian Tiger then it was a sub-adult animal.

An unpublished document of seven pages, in the archives of German Thylacine researcher and author Heinz Moeller, is dedicated to identifying Tasmanian Tiger tracks and distinguishing them from those of Tasmanian Devils, Wombats, Dogs, Brush-tailed Possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) and macropods (ie. in the kangaroo family, Macropodidae). It appears to be attributed - in handwriting (probably Moeller's own) - to Nick Mooney and dated, again, in handwriting, to circa 1988. Its title, which is also a hand-written addition, is "Tracks" but it may be the case that the document originally had no title or is an excerpt from a larger work. Moeller cites the "Tracks" document in his book Der Beutelwolf and attributes it to Mooney, circa 1988. In this article the present author follows Moeller's attribution.

The "Tracks" document addresses the question of the overlap in print size between Tasmanian Tigers and Tasmanian Devils more specifically and notes "when deciphering prints it must be remembered that individuals of a species come in different sizes either through individual variation or age differences. Thus overlap in size may be produced even between species whose adults differ significantly" (Mooney, C. 1988). In this context, he notes "the three animals most likely to be confused with [the Thylacine] either through size and/or shape" are "1) the forefeet of small wombat on hard ground where the foot and claws may be indistinct; or 2) the forefeet of large Tasmanian devils on hard ground where the thumb and rear of the pad may not show. Size suitable for small thylacine; or 3) Poor prints of medium sized dogs purely because of their appropriate size".

It is readily seen from the photographs above, on the basis of shape, that these prints were made neither by a Wombat, nor a Dog. It remains, then, that Tasmanian Devil is the strongest alternative candidate explanation for these prints and as just described, the fact these prints are significantly smaller than those expected of an adult Thylacine does not preclude the possibility of their being made by a Tasmanian Tiger.

As noted, Guiler states an adult Thylacine's stride length "should be 80cm or more" (Guiler 1985). On analysing film footage of the Thylacine, Mooney makes an observation on the ratio between stride length and shoulder height, stating the stride is "approx. 1.1 x shoulder height, about 50cm in an adult male". This may be interpreted to mean that either shoulder height is 50cm, with stride then being 1.1 x this figure; ie. 55cm, or that stride is about 50cm. Although stride length was not measured in the field for the prints in question, using the above estimate that the animal's carpal pad was 2.6 centimetres in width, this can act as a scale in the context photograph to estimate stride length. In this way, the animal's stride is estimated to be approximately 15 to 20 centimetres - a figure considerably below the estimates provided for an adult Thylacine. This does not preclude the animal from being a Thylacine but if it is a Tasmanian Tiger then it is a small one. There were no additional track lines in the mud suggesting the presence of a second animal with this one, but the extent of mud was also not very great, with surrounding terrain being stony and unsuitable for animal tracks.

Summary and conclusion

On the basis of footprint size and stride length, the track line is consistent with both Tasmanian Tiger (sub-adult) and Tasmanian Devil (adult).

Print shape and appearance

It is notoriously difficult to be certain of the appearance of Tasmanian Tiger footprints. Tasmanian Tiger footprints have variously been illustrated, cast from taxidermies, alleged in the field, inferred from fossilised track lines and inferred from tracks beside Thylacine skeletons in mainland Australian caves.

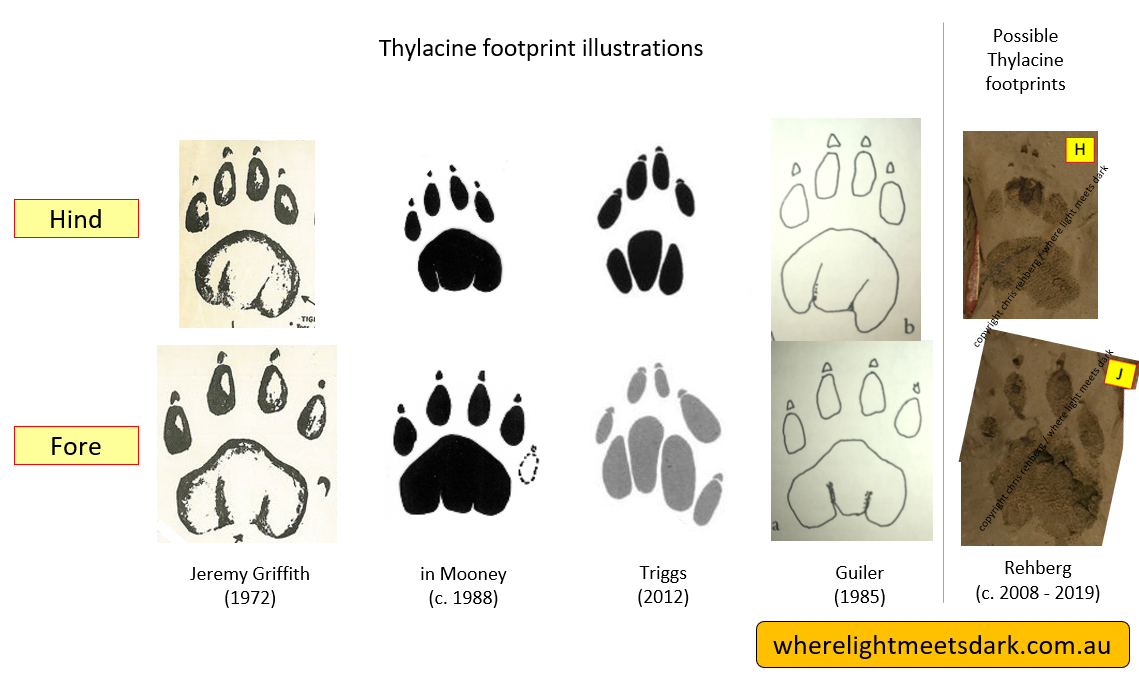

Published illustrations of Thylacine footprints

Below is a composite image showing illustrations of Tasmanian Tiger footprints by four notable researchers, together with the footprint pair H-J from the track line described in this article.

Tasmanian Tiger footprint illustrations by Jeremy Griffiths, in Nick Mooney, by Barbara Triggs and by Eric Guiler together with prints H and J from the track line observed by Chris Rehberg. Copyright: Where Light Meets Dark (utilising source images as referenced).

In the above illustration, individual prints are not to scale - in some cases the hind foot has been reduced in size relative to the fore foot illustration by the same researcher. The Triggs illustration is based on the placement of a taxidermied thylacine foot into a sandy substrate. In this author's opinion it is likely the digit placement is distorted due to the specimen being desiccated, relative to how the print of a live animal would appear. The Guiler illustration comes from his book "Thylacine, Tragedy of the Tasmanian Tiger" (1985). The Mooney illustration is used on the Tasmanian Parks website and features in the Tracks document (1988). The footprints H and J come from the right hand side of the body while the Griffith, Mooney and Triggs forefoot prints shown here are for a left forefoot. It is not clear whether the Guiler forefoot is left or right. Griffith, Mooney and Triggs show "thumb" imprints for the forefeet while Guiler leaves this mark absent. Most authors agree the thumb will only leave an imprint in deep mud.

A feature that is clear across all illustrations is that the posterior edges of the carpal (front foot) and plantar (hind foot) pads are both "tri-lobed". This appearance is emphasised in the illustrations as the line between lobes can easily be illustrated by "drawing the lines on paper". In practice it is not certain that a footprint on the ground would exhibit this feature so readily. Both prints H and J appear to show only 2 lobes. This outline perhaps best matches the Griffith illustration which presents a generally concave posterior edge to the carpal pad.

Published illustrations of Tasmanian Devil footprints

Below is a composite image showing illustrations of Tasmanian Devil footprints by three notable researchers, together with the footprint pair H-J from the track line described in this article.

While there are similarities between the Tasmanian Devil and Tasmanian Tiger illustrations, there are also some notable differences:

- The carpal (front) and plantar (hind) foot pads in Tasmanian Devils have a more rounded appearance than in Tasmanian Tigers.

- All three illustrators illustrate the presence of a thumb print on the forefoot.

- The distance between the digits and the plantar pad on the hind foot is greatly reduced in the Tasmanian Devil compared with the Tasmanian Tiger.

- Mooney's illustration shows a slight but definite variation in digit size amongst the four "finger" digits of the forefoot while Griffith and Guiler do not.

In comparison with the track line prints H and J:

- The posterior edges of the carpal and plantar pads in prints H and J are concave, unlike the Tasmanian Devil illustrations.

- There is no obvious thumb print in print J, unlike the Tasmanian Devil illustrations.

- The distance between the digits and the plantar pad in print H is not reduced, unlike the Tasmanian Devil illustrations.

- There is a variation in digit size in print J, similar to Mooney's Tasmanian Devil illustration, but unlike Griffiths or Guiler's Devil (or any of the Tiger) illustrations.

Regarding the larger gap between the plantar pad and the digits in the hind foot print H, it is notable that Guiler writes "the plantar surface of the pes [of the Thylacine] is easier to identify in the field because the spacing separating the digits and main pad is larger" (Guiler 1985).

These differences in comparison with Tasmanian Devil illustrations persist with all clear prints documented through high resolution photography (C, D, F, H, J, L, M, N, Q, R, S, U) except G (which shows a rounded posterior edge to the carpal pad - despite the same foot leaving prints with a concave edge in marks C, L and Q).

One further difference between print H and any of the Tiger or Devil illustrations is that the claw marks are positioned at a distance from the digits. This might be expected when the substrate is relatively hard and the impressions made by the digits are not deep - and this appears to be the case here.

Based on the hind foot (print H, and other marks made by the hind feet in the track line) lacking a Devil's characteristic "rounded squarish" shape and the extended distance between the plantar pad and the digits, it is arguable that the track line footprint shape is a better match for Tasmanian Tiger than for Tasmanian Devil. Further, Mooney notes a Thylacine's tracks may be confused with "the forefeet of large Tasmanian devils on hard ground where the thumb and rear of the pad may not show" (Mooney 1988). Although the mud in which these tracks was found appears to have been somewhat dried and firm, the clarity and accuracy of the digit marks left by those digits which did leave marks (ie. in essentially every print) suggest that if the animal was a Tasmanian Devil, it could be expected to have left unambiguous thumb prints in at least some of the footprints. That it should have left thumb marks is implied by Mooney's note and all of the Tasmanian Devil footprint illustrations, and yet it hasn't, beyond possible dew claw marks in just two prints. Despite these several details suggesting a better match for Tasmanian Tiger, this author takes a conservative interpretation and allows that the substrate may have been firm enough to result in atypical prints being formed, should the animal have been a Tasmanian Devil.

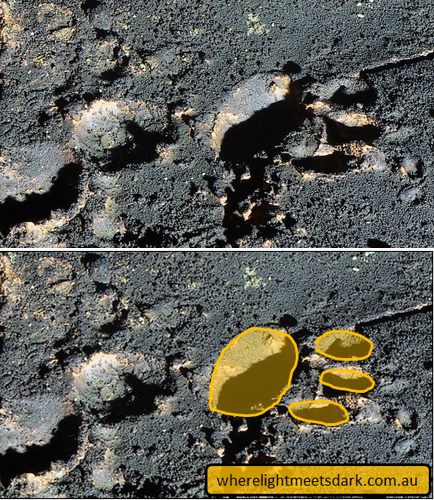

Tasmanian Devil footprint examples showing characteristic shape

At various points in this article, Tasmanian Devil footprints are variously described as "squarish" and "rounded", seemingly in contradiction. The photographs below illustrate what is meant by this description: the overall proportions of each print are roughly square and yet the plantar pad, and the shape overall has a rounded appearance.

Tasmanian Devil footprint in sand, traced to show overall shape.

Tasmanian Devil footprint in mud, traced to show overall shape.

In both the above cases, the digits are positioned adjacent to the carpal/plantar pad, in contrast with the illustrations for Tasmanian Tiger and in contrast with the hind foot prints in the track line being evaluated.

Jewel Cave Thylacine tracks

Perhaps the only undisputed Tasmanian Tiger track comes from Jewel Cave in Western Australia. The skeletal remains of a Tasmanian Tiger were discovered in the 1960s, lying next to a set of footprints interpreted as belonging to the animal. The footprints were photographed in the 1990s and one photograph was published in 2011 (Towie, 2011).

Tasmanian Tiger footprint from Jewel Cave, Western Australia. Overlaid image copyright: Where Light Meets Dark, using source image by Augusta Margaret River Tourist Association.

The Jewel Cave print is unusual in that only 3 digits are readily apparent. The imprint seems deep enough, and the substrate consistent enough, that a fourth digit should have shown clearly. Its absence is unexplained. It is unclear whether this print represents a forefoot or hind foot but in some respects it appears to be a better match for a Tasmanian Devil hind foot, on account of the "rounded" appearance of the plantar/carpal pad. There appear to be two additional impressions behind the footprint and these lack the suggestion of any digits, although one of these impressions is not seen fully in the image. Although this footprint most likely originated with a Tasmanian Tiger, it varies significantly from the illustrations of the various accepted authorities discussed above. The implications are that either our documented understanding of Thylacine tracks is in error, or the shape of the Jewel Cave print is an anomaly, or the skeleton with which it was associated was incorrectly identified (and may have been a Devil) or it did not originate with the skeleton found nearby (if it is verified as a Thylacine).

Thylacine foot taxidermy

The photograph below is published in the fourth revision of the International Thylacine Specimen Database (Sleightholme and Ayliffe, 2011) and is included in this author's Animal Tracks Library (Rehberg, undated E).

Thylacine forefoot taxidermy with carpal and digital pad outlines traced. Copyright: Where Light Meets Dark.

In this photograph the pads have been traced approximately as a means to estimate how the various foot pads might appear in a footprint. As with the Triggs illustration, the use of a taxidermy for estimating footprint shape is questionable as the taxidermy is desiccated and obviously the animal is not using its digits for balance, stability and locomotion whilst "making a print". There is some variation in digit size, however - a feature not noted in any of the Tasmanian Tiger illustrations, but noted for the Tasmanian Devil in Mooney's illustration.

Skin texture

The photographs of marks H, J, R and S all clearly show "pock mark" indentations in the substrate. These correlate to nodules, or bumps, on the surface of the animal's skin. This skin texture is consistent with both Tasmanian Devils and Tasmanian Tigers, as seen in the photographs below.

Tasmanian Devil feet showing nodule texture. Copyright: Dr Marissa Parrott (2017).

The photograph above shows a live Tasmanian Devil foot where the bumpy "nodule texture" is apparent on the skin.

Tasmanian Tiger feet of Museum Victoria specimen C3149 showing nodule texture. Copyright: Museum Victoria / Kevin C. Rowe.

The photograph above shows museum taxidermy C3149 (Museum Victoria). Although the specimen is approximately one century old, a similar "nodule texture" on the skin is still evident.

It is clear from these two photographs that the skin texture exhibited in the track line observed in Tasmania, is insufficient to ascertain species.

Intra-foot measurement ratios

Consideration must be given to whether measurements of various foot elements may lead to species identification. For example, it may be the case that the length of the first digit on the forefoot, exhibits a consistent ratio with respect to the length of the carpal pad on that same foot, for a given species, and that the ratio varies between species. Such metric analysis of the relative ratios of the lengths of various body parts forms a significant portion of Moeller's work in Der Beutelwolf (1997). Moeller was working, however, with skeletal and taxidermied material; not footprints.

Anecdotally, the distance between the digits and the plantar pad in the hind prints S and H appears greater than that expected of a Devil, and more consistent with Thylacine, based on Griffith, Mooney and Guiler.

It is this author's contention, however, that such ratios as measured in footprints will vary in accordance with the physical properties of the substrate in which a print appears (particularly moisture content and depth) relative to the weight of the animal leaving a print. For fixed conditions, such ratios may also be consistent when measured from footprints, but substrate conditions are invariably inconsistent between footprints observed in the field.

As such, no firm conclusion can be drawn from intra-foot measurement ratios without first establishing the effect of substrate properties, and animal weight, on print impressions under controlled conditions. Whilst this would be interesting research in its own right, footprints in the field are typically discovered following an unknown period of time after which they were left by an animal. This means that substrate conditions at the time of impression will be difficult to ascertain for almost all prints discovered in the field. Further, the conditions and impacts of weathering during this unknown period of time will also have a bearing on the impression finally observed.

Given the above, intra-foot measurement ratios measured in footprints are unlikely to provide any useful information toward ascertaining species (ie. where the difference between the species is marginal, as between Thylacine and Tasmanian Devil).

Summary and conclusion

By inspection of the various sources above, it is clear the appearance of Tasmanian Tiger track illustrations varies between illustrators. Compare, for example, Griffith, Mooney and Guiler as a set (all similar to one another) with Triggs and then with the Jewel Cave print tracing and the Thylacine taxidermy tracing.

It must be concluded that illustrations are indicative only. This is perhaps not surprising, as "in the real world" the individual footprints made by an individual animal will vary from step to step - and so any single illustration designed to summarise a species must be a generalisation. To illustrate this contention it is simple to visit any sandy beach where dogs have been and to examine the variety in prints left by a single animal.

Secondly, the illustrated Tasmanian Tiger tracks are generally similar to illustrations of Tasmanian Devil tracks. Whilst on paper, subtle distinctions may be noted between the species, in reality these distinctions will likely prove very difficult to establish. Perhaps Nick Mooney said it best when he wrote "It is obvious that to be positively identified, a thylacine print, unassociated with a characteristic gait, would have to be of very good quality" (Mooney, C.1988). Some footprints may be clearly identified as being from a Devil - most specifically the hind foot when it exhibits a classic squarish shape, but not all.

Skin texture in the observed track line is consistent with both Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil.

Anecdotally, the hind foot impressions of the track line show a better resemblance to the Tasmanian Tiger illustrations than to Tasmanian Devil illustrations (notably the distance of the digits from the plantar pad), but it is arguable that intra-foot measurement ratios in footprints do not contribute useful information toward identification on the grounds they are almost certainly influenced by the substrate's physical conditions at the time an impression is made, and subsequent weathering.

On the basis of shape and appearance, the track line is consistent with both Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil.

Gait and footstep patterns

What is meant by gait - terminology

The term "gait" is generally used to describe one of two things:

- Either, gait is meant to describe the motion of an animal's body as it moves (cf "ambling gait", "rocking gait", "loping gait"),

- Or, gait is meant to describe the placement of feet on the ground during locomotion.

The manner of locomotion determines the foot placement on the ground.

In this analysis, as we are considering footprints observed on the ground, we are concerned with an animal's footprint patterns. In general, this section uses the term "gait" to represent body movement, and "footprint pattern" to represent the footprints left by an animal. Note, however, that various source materials will use the term "gait" to represent footprints on the ground.

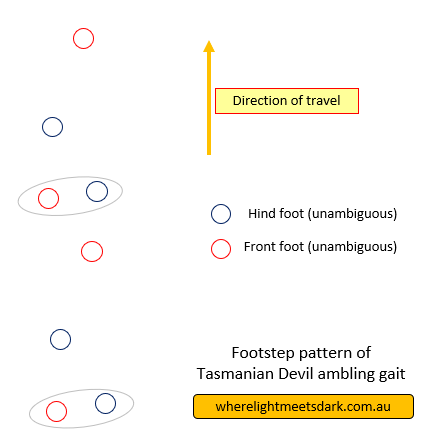

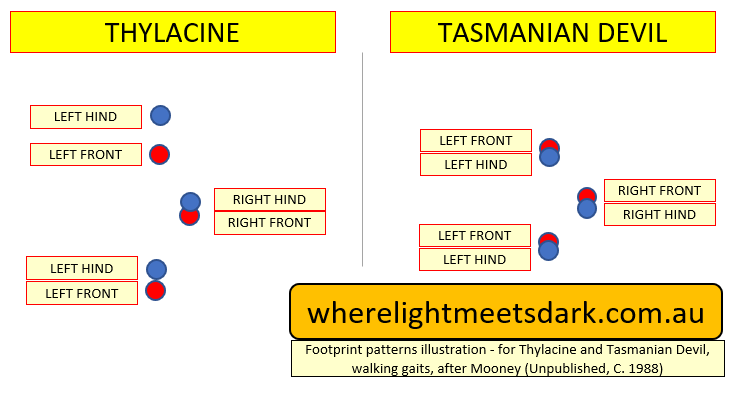

Tasmanian Devil ambling gait footprint pattern

The Tasmanian Devil uses a number of gaits for locomotion. The diagram below illustrates the tracks left by the Tasmanian Devil's "ambling" gait.

Tasmanian Devil ambling gait footprint pattern. Copyright: Where Light Meets Dark.

The illustration above shows that in the Tasmanian Devil's ambling gait, footprints are paired from either side of the body. These are shown within the grey ovals: in this case a left front foot is paired with a right hind foot and the footprints lie side by side. Ahead of such a pair of footprints you see a single print from one side of the body - here, a left hind print - and then from the other side of the body - here, a right fore foot - and then the pattern is repeated. The entire track line may appear as shown here, or mirror-imaged (left to right) as different devils favour different sides of the body when ambling.

In contrast, the track line being described in the present analysis exhibits a "walking" gait. The walking gait is "very rarely used [by Tasmanian Devils] and then only for short periods, such as when investigating an object", according to Mooney (C.1988) and used "when traveling slowly", according to Triggs (1984). Elsewhere in the Tracks document, Mooney notes that partial heel prints in Tasmanian Devil tracks were observed at a rate of approximately 0.01% of prints (ie. 1 in 10,000 prints). This author surmises that tens of thousands of Tasmanian Devil footprints were evaluated in order to draw the conclusions described; ie. that is to say tens of thousands of devil footprints were evaluated before drawing the conclusion that Tasmanian Devils very rarely use a walking gait, and then only for short periods such as when investigating objects.

It can be seen from the track line context photograph that the 20 marks recorded on the ground were placed in a relatively straight line through a patch of mud - unlikely to be associated with the investigation of any object.

Simply by virtue of being an extended walking gait, the track line appears more likely to have been made by a Tasmanian Tiger than a Tasmanian Devil. There are, however, additional means by which to distinguish the species using a track line, as described below.

Using footprint patterns to identify Thylacines

Mooney describes gaits and footstep patterns for a number of Tasmanian species (C.1988). Importantly, regarding the Thylacine, he notes:

- "Positive identification of thylacine by gait [ie. footprint pattern] along [sic: alone] (if prints are of suitable size but of poor quality) is difficult", but also

- "to be positively identified, a thylacine print, unassociated with a characteristic gait [ie. footprint pattern], would have to be of very good quality"

In other words,

- an isolated footprint, may be sufficient to distinguish Thylacine from Devil, but only if it is very good quality, and

- a track line showing the correct pattern of footprints, but without sufficient clarity in the individual prints to ascertain that Thylacine is a viable candidate, is inadequate on its own to identify Thylacine.

More importantly, Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil track lines may be distinguished by footprint pattern (ie. so long as the individual prints forming the track line are clearly candidate prints for those two species).

It was shown above that the footprints being described in this article are consistent with both Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil. What remains then, is to consider whether the footprint pattern exhibited in the track line better matches Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Devil.

Illustrations of Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil footprint patterns

The illustration below is after Mooney (C.1988).

Walking footprint patterns for Thylacine and Tasmanian Devil, after Mooney (C. 1988). Copyright: Where Light Meets Dark.

Tasmanian Devils exhibit a number of gaits - in the sense of body movement - and presumably so do Tasmanian Tigers. The figure above illustrates the "walking" gait footprint patterns for Tasmanian Tigers (at left) and Tasmanian Devils (at right). The general pattern in each case is for there to be two prints in close proximity to each other (ie. paired) on one side of the body, and then a little later, two prints similarly paired on the other side of the body, and this pattern repeats.

The key distinction between Tasmanian Tigers and Tasmanian Devils is seen when considering each pairing of prints:

- in Tasmanian Tigers, the hind foot (blue dots) lands ahead of where the front foot was placed (red dots)

- in Tasmanian Devils, the hind foot (blue dots) lands behind where the front foot was placed (blue dots)

This is why gait alone is insufficient to distinguish Tasmanian Devil from Tasmanian Tiger - there must be sufficient clarity of individual footprints to discern forefoot from hind foot in order to ascertain species. The track line being analysed here exhibits superbly fresh, well-preserved prints making forefoot and hind foot distinction unambiguous in most cases. Further, the number of prints being clearly preserved is very significant, as long track lines such as this one are rarely observed in Tasmania except on beaches and sand dunes.

Interpretation of the track line footstep pattern

The track line exhibits 8 apparently clear pairings of footprints. Pair D-E was flagged as tentative in the discussion above, on account of the footprints being somewhat distanced from each other, although they both appear to be on the same side of the track line (ie. right hand side of the body). The track line footstep pattern is illustrated below.

Footstep pattern of the track line observed in Tasmania by Rehberg. Copyright: Chris Rehberg / Where Light Meets Dark.

As noted earlier, A and B may form a pair, or B and C may form a pair. C may be an overprint. E is believed to form a pair with D and therefore E is inferred to be a front foot (as D is an unambiguous hind foot). P is believed to form a pair with Q and therefore is inferred to be a hind foot (as Q is an unambiguous front foot). T may be an overprint.

Analysing the eight pairings that were documented through high resolution photography, we have:

| Pairing | Consistent With |

|---|---|

| D-E* | Thylacine |

| F-G | Thylacine |

| H-J | Thylacine |

| K-L | Thylacine |

| M-N | Thylacine |

| P-Q | Thylacine |

| R-S | Devil |

| U-V | Thylacine |

*D-E is a tentative pairing, as described above.

Overwhelmingly the track line is more consistent with the illustration for the Tasmanian Tiger's walking gait footprint pattern, than that of the Tasmanian Devil's (87.5% match for Thylacine if including the D-E pair; 85.7% match if ignoring the D-E pair; 88.9% match for Thylacine if including both D-E and B-C as pairs).

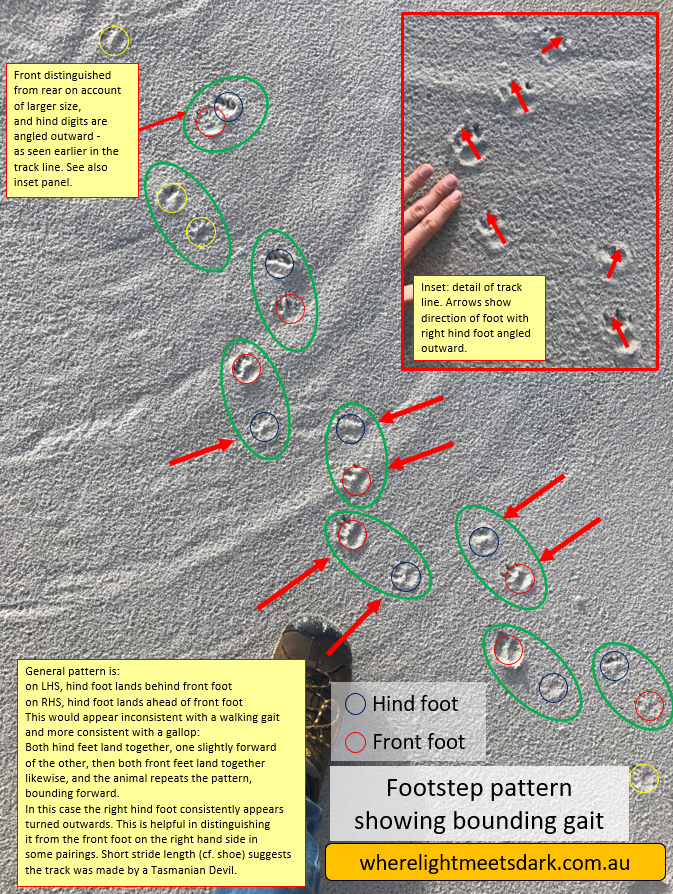

Comparison with an additional novel footprint pattern observed in Tasmania - Tasmanian Devil bounding gait

In preparing this analysis the author was unable to locate a photograph of Tasmanian Devil tracks formed during the walking gait either within his own collection or online. A photograph was located, however, of a track line in which the placement of feet on the ground in general, exhibits the same distribution of footprints as seen for a walking gait, but the specific positioning of hind foot relative to front foot varies from both walking gait models illustrated by Mooney.

This author proposes the footprint pattern described below originates with a Tasmanian Devil exhibiting a bounding gait whereby both hind feet land near-simultaneously and then both forefeet land likewise.

Footprint pattern interpreted as originating with a Tasmanian Devil bounding gait. Copyright: Chris Rehberg / Where Light Meets Dark.

Several features are illustrated in the image above.

The key feature to note is that if the footprints are paired as illustrated via the green ovals, then on the right hand side of the body, the hind foot (blue circles) lands ahead of the fore foot (red circles) while on the left hand side of the body, this pattern is reversed: on the left hand side, the hind foot (blue circles) appears to land behind the fore foot (red circles). There is no logical walking gait by which the animal may produce this pattern (and actually successfully walk without falling over). Rather, the interpretation here is that the animal is bounding: two hind feet (a pair of blue circles) land together, and then two forefeet (red circles) land in front of them. The hind feet are drawn up, then the forefeet are drawn up also and the pattern repeats, with the animal landing again on its two hind feet. This reversal of foot positions on either side of the body is illustrated by Triggs in her assessment of the Spotted-tailed Quoll's "slow bounding track" (Triggs, 1984 p81) further supporting the interpretation that the footprint pattern in the photo above was created via a bounding gait.

The above pattern is important because without sufficient clarity to discern forefeet from hind feet, the overall placement of feet on the ground matches that of the walking gait. In comparison, the track line that is the main subject of this article exhibits a walking gait footstep pattern and not a bounding gait footstep pattern.

Red arrows in the above illustration, main panel, indicate footprints for which high resolution photographs were taken. Six of these are shown again in the inset panel. Red arrows in the inset panel indicate the direction of travel for individual footprints, and it is noted that the right hind foot is consistently turned outward. This feature, probably unique to this animal, is used to further confirm foot placements on the right hand side of the animal in the main image. A few footprints are circled in yellow, indicating the detail available in the photograph is insufficient to firmly distinguish between fore and hind foot. On the left hand side, the larger footprint is understood to be from the fore foot. Technically, without having observed the animal producing this track line, it may in theory have equally been produced by either a Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Devil. The short stride length (approximately equivalent to one shoe-width, per the photo), more characteristically squarish, but rounded plantar pad, and track location (in close proximity to human habitation near Granville Harbour on Tasmania's west coast), lead this author to conclude the track line was made by a Tasmanian Devil. The more rounded plantar pads and short stride length also contrast with the track line under primary consideration in this analysis.

In summary, this author concludes the track line on sand presented in this section is originates with a Tasmanian Devil engaging a bounding gait. It differs from the primary subject of this article in print shape, footprint pattern and stride length. To emphasise, the primary track line being analysed in this article represents a walking gait, in contrast to the Devil track line shown here in sand.

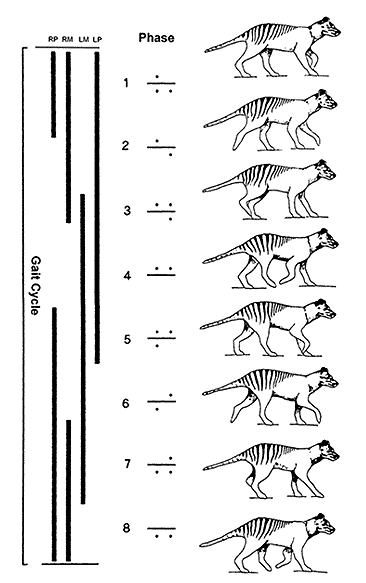

Comparison with Thylacine Museum gait animation and Moeller gait analysis

The online "Thylacine Museum" presents an interactive animation of a walking Tasmanian Tiger. Visitors to the website may zoom in on the animation and rotate it for viewing from any angle. The animation was "created by Arnfinn Holderer (2016) after Moeller (1997) with technical contributions from C. Campbell and Dr. S. Sleightholme" (Campbell, undated B). The animation is based on a series of illustrations by Moeller, as shown below.

Gait cycle of the Thylacine. Copyright: Heinz Moeller (1997).

Moeller based his analysis of Thylacine gaits primarily on the motion footage of Tasmanian Tigers captured by David Fleay. Moeller's primary concern in describing the Thylacine gait was in evaluating which feet were in contact with the ground at different points during the Thylacine's walk. As can be seen from his illustrations, the Thylacine has, at various stages throughout its walk cycle, either two or three feet positioned on the ground at the same time. Whilst none of Moeller's illustrations indicate the relative placement of the hind foot with respect to the fore foot, the animation at the Thylacine Museum clearly has the hind foot landing behind the front foot at each step. This positioning is at odds with Mooney's illustration of the footstep pattern for the Thylacine's walking gait. On querying this discrepancy with one of the animation's technical contributors, it was confirmed that the relative foot placement in the animation was not specifically modeled after any earlier reference material (Sleightholme, pers. comm. 2019). As such, the animation is not documentary for relative foot placement and footprint patterns.

Additionally, the four vertical bars on the left hand side of Moeller's illustration indicate which of the Thylacine's feet contact the ground simultaneously. The initials above the four lines are English translations of the original German and can be interpreted as follows:

- RP = Right Pes (hind foot)

- RM = Right Manus (front foot)

- LM = Left Manus (front foot)

- LP = Left Pes (hind foot)

Scanning across the vertical lines, wherever the lines are present for both right feet (RP and RM), the corresponding illustration shows the right forefoot extended ahead of the animal and the right hind foot behind the animal. The same is true for the left hand side of the animal (LM, LP). More specifically, there is no illustration showing a hind foot on the ground simultaneously with the front foot on the same side of the body, where those two foot placements are in close proximity - ie. per the pairs of footprints being analysed in this article. If such foot placement were to be found in Moeller's descriptions, it would be physically impossible for the hind foot to be positioned directly ahead of the forefoot, on the ground, at the same time as that forefoot placement. Rather, what we see is that Moeller's descriptions of the Thylacine walking gait are consistent with the movement that would be required to allow the footprint pattern illustrated by Mooney.

Further, although Moeller cites Mooney's Tracks document (p 27), that reference is in relation to a reproduction of the footprint illustrations as shown above. There is no mention of Mooney's footprint pattern illustration informing Moeller's analysis of gait.

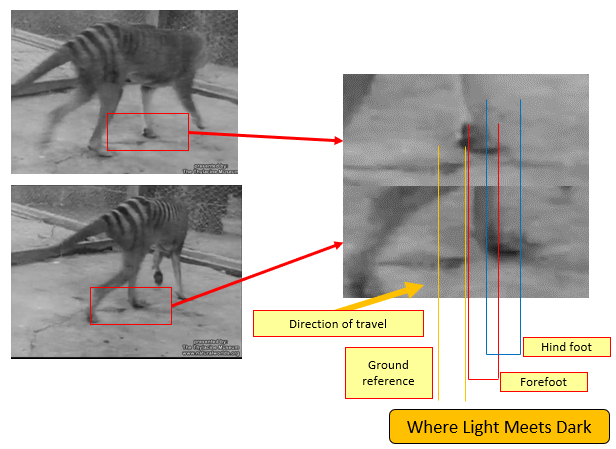

Comparison with archival film footage by David Fleay

Any consideration of Thylacine gait must take into account archival film footage of the species; in particular, that captured by David Fleay. Although this section is not a comprehensive analysis of every possible still frame, it can be seen that circumstantially, the Thylacine in Fleay's footage appears to position its hind foot ahead of where its fore foot lands, as it walks about its enclosure. Two instances are examined below, whereby there are still frames clearly showing forefoot and hind foot placement relative to an unmoving reference point (in both cases, marks on the ground) that is very near the positions where the feet are placed. All still frames come from footage hosted at the Thylacine Museum website (Campbell, undated C).

Still frames from historical film footage by David Fleay analysing Thylacine foot placement - composite A.

In the first instance, the Thylacine is walking away from the camera and about to engage in a left-turn within its enclosure. On the left hand side of composite image A, the two still frames have been reduced in size. In the upper frame the left forefoot is contained within the red box and this portion of the still frame is enlarged to the right. In the lower frame, the corresponding left hind foot is contained within the red box and this portion of the still frame is enlarged to the right.

The right hand side of composite image A uses a number of coloured lines to illustrate relative foot placement:

- The orange lines indicate the left and right extremity of a mark that is on the ground and unmoving. These lines were placed on the portion of each frame where the pixelation was darkest for that mark on the ground. The two frame portions were aligned (left to right).

- The red lines show the rear (at left) and leading (at right) edges of the forefoot (in the upper frame). The lines were placed where the pixelation along the lowest edge of the foot was darkest and where the shape of the foot is lowest within the frame (ie. nearest to ground).

- The blue lines show the rear (at left) and leading (at right) edges of the hind foot (in the lower frame). These lines were likewise placed where the pixelation along the lowest edge of the foot was darkest and where the shape of the foot is lowest within the frame (ie. nearest to ground).

- In all cases the lines have been extended into the second frame (ie. the red lines, positioned according to the forefoot in the upper frame have been extended down into the lower frame and the blue lines similarly extended upward from the lower frame into the upper frame).

- A horizontal line has been added to the bottom of the red and blue line pairs - this horizontal line approximates the length and position (relatively speaking, from left to right only) of the fore (red) and hind (blue) feet.

Note the orange arrow labelled "Direction of travel". It can be seen that with the animal traveling generally left to right, the hind foot is positioned ahead of where the fore foot was placed. This is consistent with Mooney's illustration for the footprint pattern seen resulting from the Thylacine's walking gait (Mooney, C. 1988). There is some overlap of the footprints in the left-right axis as we see it, but on the ground it is possible that the two feet are offset left-right (ie. beside each other) relative to the direction of travel.

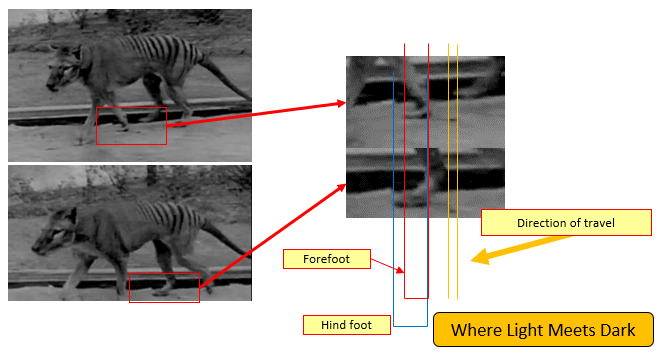

Still frames from historical film footage by David Fleay analysing Thylacine foot placement - composite B.

In the second instance, the Thylacine is walking from right to left in the frame. The analysis follows the same process just described for composite image A, in mirror-image. In conclusion, the trailing edge of each foot appears to land at the same place while the leading edge of the hind foot appears to land ahead of the leading edge of the forefoot.

There are additional frames between the two used in composite image B and one of these frames shows both feet in very close proximity during the action of this step.

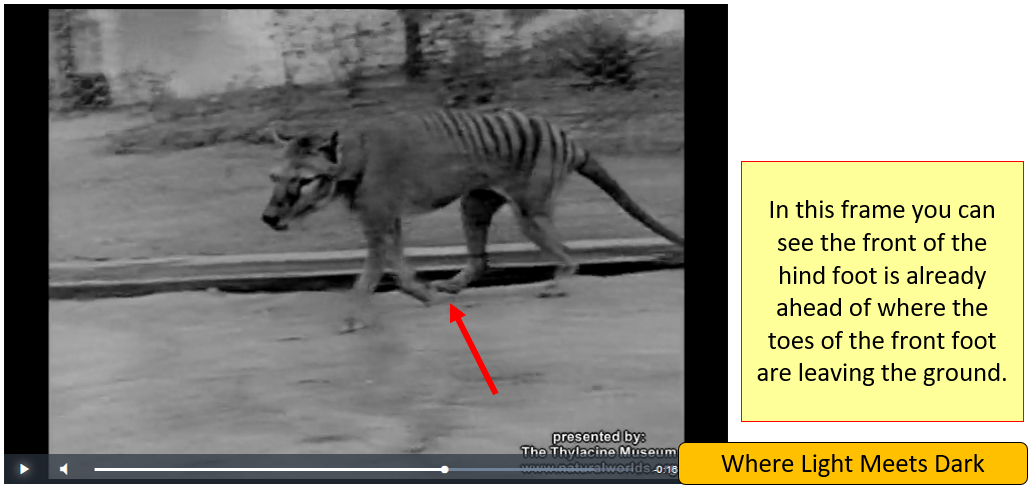

Still frame from historical film footage by David Fleay analysing Thylacine foot placement - image C.

In this frame the right forefoot is barely touching the ground. It is inferred that the foot pads on that foot are actually now facing away from the ground and upward and rearward. If it were possible to "rewind" the footage, then for those pads to re-contact the ground (in reverse), the foot would be rotated around that point where it now barely touches the ground, resulting in the foot pads contacting the ground just behind that point where the foot now touches the ground. The leading portion of the hind foot is thus seen to presently be marginally ahead of where the fore foot's footprint may be expected. This interpretation corresponds with the measurements illustrated in composite image B. This still frame also illustrates that the fore foot is indeed lifted out of the way before the hind foot is placed on the ground - as inferred earlier by analysing Moeller's conclusions about Thylacine locomotion (which were based on Fleay's footage) and as would be required in order for the footprint pattern illustrated by Mooney to be a plausible pattern for a walking gait.

There are several important considerations regarding the above analysis. Firstly, it must be noted that this cursory analysis uses a digital encoding of the original film and this has technical limitations, including the possibility that the encoding itself may introduce artefacts into still frames, as described in Rehberg (2006). In an analysis where differences in results are "pixel thin" (ie. measurements of just a few pixels), such artefacts may affect the accuracy of conclusions. Secondly, a still frame is the result of a three dimensional scene (the Thylacine, in life) projected onto a two dimensional medium (the film reel). The analysis has relied on the left-right positioning, in the two dimensional field, of the foot placements. In life, however, if the Thylacine offsets the placement of its hind foot left or right, on the ground, relative to the direction of travel, then this "real life" offset may project to the two dimensional still frame in a way that impacts the left-right positioning being analysed (ie. in the still frame). For this reason alone, any conclusion regarding foot placement must be tentative unless a comprehensive analysis can be made of as many footsteps as possible, taking into account this modeling of the three dimensional scene onto the two dimensional film reel. Thirdly, in composite image A, the Thylacine engages in a left turn with the next step after the one being analysed. It is conceivable that the step being analysed may not be typical for steps taken when traveling directly ahead, as it may have been influenced by the animal's intention to turn. Finally, a comprehensive analysis may conceivably find counter-examples which support the conclusion that the hind foot is in fact placed behind where the fore foot lands.

Given this considerable list of caveats, it can still be said the final image C supports Moeller's conclusions regarding the Thylacine's walking gait; namely, that the forefoot is lifted out of the way before the hind foot lands. The two composites A and B circumstantially appear to support the view that the hind foot is in fact placed equally or slightly ahead of where the forefoot has landed - as described by Mooney - but this cursory analysis of the Fleay footage must be regarded as inconclusive in this regard. There may be merit in conducting a more comprehensive assessment of the Fleay footage.

Summary and conclusions

There is one key reference documenting the Thylacine's footprint patterns - an unpublished document on various Tasmanian mammal tracks, attributed to Mooney circa 1988, located in the archives of Heinz Moeller. This document includes the Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil footprint illustrations currently in use on the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service website. It also illustrates the relative foot placement in the walking footprint patterns of Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil track lines. In particular it distinguishes between the species, with Tasmanian Tigers placing their hind foot ahead of where the front foot had landed and Tasmanian Devils placing the hind foot behind where the front foot had landed.

Despite Moeller citing the Tracks document in reference to Thylacine footprint illustrations, the Tracks document appears not to have informed Moeller's assessment of Thylacine gait. Rather, that analysis is mostly based on the David Fleay film footage of Thylacines. Professor Moeller produced a diagram and drawings that illustrate which of the Thylacine's feet contact the ground simultaneously as it walks. It stands to reason that in order for a hind foot on one side of the body to leave a footprint directly in front of the corresponding front foot, that front foot has to be lifted out of the way of the incoming hind foot. Moeller's research, based on the film footage, indicates that this lifting of the forefoot before placement of the hind foot is, in fact, what happens during the Thylacine's walking gait and therefore placement of the hind foot ahead of the corresponding front foot - as illustrated by Mooney - is viable. A cursory examination of the Fleay footage shows Moeller's description (of the forefoot lifting away) to be accurate. A more comprehensive analysis of the Fleay footage would be required before a conclusion could be drawn on whether Mooney's illustration is accurate in showing the hind foot landing ahead of where the fore foot was placed. This specific arrangement of foot placement, however, is seen in the track line that is the primary subject of this analysis in over 85% of footprint pairings and contrasts directly with the foot placement expected of a Tasmanian Devil, as illustrated in the same document.

On the basis of footprint pattern, the track line is consistent with Tasmanian Tiger, but not Tasmanian Devil.

Conclusion

Many features of the track line and its constituent footprints have been analysed. These are summarised below.

| Feature | Observation | Consistent with Tasmanian Tiger | Consistent with Tasmanian Devil |

|---|---|---|---|

| Print Size | Overall length and width of fore and hind foot | ||

| Print Shape and Appearance | General appearance | ||

| Print Shape and Appearance | Skin texture | ||

| Print Shape and Appearance | Intra-foot measurement ratios | ||

| Gait | Footprint pattern |

On balance of measures and within the scope of current knowledge, the track line is more consistent with having been produced by a Tasmanian Tiger than a Tasmanian Devil.

This may be explained in numerous ways, including:

- A Tasmanian Tiger produced the track line, if the species is not extinct (despite being so categorised);

- A Tasmanian Devil produced the track line, if that species produces the footprint pattern observed (despite being documented as producing a different pattern).

It should be clear that the first interpretation is difficult to test but the second interpretation should easily be testable. It would seem pertinent that research be conducted on verified Tasmanian Devil walking gait footprint patterns, in an attempt to ascertain whether that species ever produces a pattern similar to the track line described in this article.

Recommendation

The conclusion above is specifically framed in terms of "current knowledge and understanding" about Tasmanian Tiger and Tasmanian Devil footprints and track lines.

There appears to be no authoritative published information regarding Tasmanian Tiger footprint patterns. This analysis has relied on the unpublished description by Mooney, and inference deduced from Moeller's published gait description, with these two sources being in accord with one another in supporting the possibility of the pattern described by Mooney - that of the hind foot print lying ahead of the corresponding forefoot print.

As the opportunity for studying Thylacine locomotion is essentially non-existent (even should the species be extant), the obvious area for research that can further substantiate or negate the above conclusions lies in studying Tasmanian Devil footprint patterns.

It is recommended a study be conducted in which the goals are to obtain clear footprints in a contiguous track line from Tasmanian Devils exhibiting a walking (not ambling, not bounding) gait.

Footprints must be clear enough to discern forefoot from hind foot. The key metric for investigation is how often Tasmanian Devils place their hind foot on the ground forward of the fore foot's footprint.

- Should such research show that Tasmanian Devils consistently place their hind foot behind the fore foot's footprint (in keeping with Mooney's document), this would strengthen the conclusion that the track line described in this article did not originate with a Tasmanian Devil. By virtue of every aspect of the present track line matching known features for Tasmanian Tiger, and with the added input of such research results, an identification of Tasmanian Tiger is strengthened.

- On the other hand, should such research show that Tasmanian Devils do consistently place their hind foot ahead of the fore foot's footprint (as seen in the track line described above), this would support the conclusion that the track line described above may feasibly have been produced by a Tasmanian Devil and that the pattern illustrated by Mooney may not be accurate for Devils in all cases.

- Should such a study show that Tasmanian Devils occasionally or inconsistently place their hind foot ahead of the fore foot's footprint (ie. and occasionally or inconsistently place their hind foot behind the fore foot's footprint as well), this would show that the track line described in this analysis may have been made by a Tasmanian Devil. The strength of such a conclusion may be open to interpretation.

- It should be borne in mind that in the observed track line, over 85% of the paired prints exhibited a hind foot placed ahead of the fore foot's footprint.

- If such study replicates results against multiple devils of varying age and sex, then a comparable measure of the incidence of this footprint pattern may be calculated. If the incidence of this pattern (hind foot ahead of forefoot) approaches or exceeds 85%, this would suggest the track line in this analysis may reasonably have been produced by a Tasmanian Devil. However, should the incidence of this pattern "not come close" to 85% - where "close" is subjective - a conclusion on species identification remains open to interpretation and debate.

Footprint shape is almost certainly influenced by multiple environmental factors and is not relevant to the proposed study, except that forefoot must be discernible from hind foot.

Persons having access to Tasmanian Devils or imagery of their walking gait footstep patterns are encouraged to contact the author and, ideally, submit photographs for the author to analyse.

Media enquiries

Media enquiries regarding access to all 10 high resolution photographs are directed to the contact form at www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au.

Fundraising

The author intends to continue searching for evidence of the persistence of the Tasmanian Tiger in Tasmania. In particular, one project area will focus on using animal tracks to identify Tasmanian Tigers. Please consider making a donation if you would like to support the author financially, via the contact form at www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au.

Appendix 1 - Rationale for selection of published data

The questions considered below are drawn from the "decision tree for publishing biodiversity data from monitoring and surveying" (Tulloch et. al, 2018). This section lists decision tree questions (quoted) followed by this author's evaluation of the most probable response to the question, in relation to the Tasmanian Tiger, and the rationale for this response.

"Is species at risk of exploitation due to in situ or ex situ value or persecution?"

Author responds: Yes.

Rationale: Historically the Thylacine was persecuted and this persecution is undoubtedly a major contributing factor to its population crash in the early 20th century. Despite belated protection of the species, a cursory examination of public discourse on probable outcomes in the event the species is rediscovered reveals considerable concern that some members of the community may be motivated to continue this persecution. Realistic potential threats to the species include all of the following, as described generically in Tulloch et al, 2018: Collection for international wildlife markets; Collection for pet trade; Recreational hunting; Recreational disturbance for wildlife watching; Killing/habitat destruction to prevent conservation.

"Is species' primary threat wildlife trade (ex situ economic value)?"

Author responds: No.

Rationale: On the basis of anecdotal commentary concerned with the possibility of persecution of the species in order to prevent economic impact on primary industries - whether a realistic threat or not - a conservative approach is taken, treating this potential threat seriously. In this author's opinion, if this threat is real it has a greater probability of eventuating than capture of specimens for wildlife trade on the basis that there are far more stakeholders with vested interest in primary industry within close proximity to the species' distribution. Further, destruction of the species is more easily achieved than extraction of live specimens for wildlife trade and therefore wildlife trade is not perceived as the species' primary threat.

"Is species' primary threat exploitation for food/medicine/other resources (ex situ economic or cultural value)?"

Author responds: No.

Rationale: Per prior question.

"Is species threatened by disturbance due to human access e.g. toursim (in situ value)?"

Author responds: Yes.

Rationale: There are historical accounts of the sudden influx of tourists to remote Tasmanian locations following allegations of sightings of the Thylacine.

"Would sharing location data increase risk of species decline through increased visitation (e.g. pathogens, trampling)?"

Author responds: Yes.

Rationale: Per prior question. Also, "almost certainly the thylacine is territorial" (Mooney, 1984); visitation risks disruption to any individuals residing within the area visited which presently has unknown impacts and therefore a conservative response is adopted.

"Are conservation/policy mechanisms in place to mitigate declines?"

Author responds: No.

Rationale: Whilst the Thylacine does have some legal protection measures in place, it is also listed as extinct. The net effect on protection for the species while it has these mixed statuses is unknown. Further, the Thylacine is believed to occupy home ranges that may span vast areas. On this basis it is likely that the thylacine traverses a landscape divided by multiple tenures having a variety of human stakeholder interests. Given the complexity of this situation, expert opinion is required to evaluate whether existing conservation and/or policy mechanisms would be adequate to mitigate declines. In this author's opinion such expert input and the input of stakeholders having the authority to form conservation policies and mechanisms has not, to this date, been as forthcoming as it might, on account of the species' present listing as extinct. It is hoped in light of this track line as evidence of the species' persistence that such considerations may now receive the input of those in best position to action conservation measures for the species and for this reason the conservative response is adopted. (Cf. the changing data protection requirements of the Night Parrot before and after protection mechanisms were employed, in example 1, Table 3, Tulloch et. al 2018.)

"Could data be used to mitigate threats to species in this or other locations?"

Author responds: No.

Rationale: While location data could be utilised to mitigate *some* threats to the species - for example, through informing conservation programs which might protect habitat - publication of data at this stage, without clear conservation protections enacted in law, yields greater risks for facilitating persecution or exploitation of the species that outweigh any perceived conservation benefits. Further, location information may still inform conservation efforts without the need for publication of this data.

The above responses to the decision tree framework yield the following publication outcome:

"Restrict data: mask species locations; not IDs" giving "Night parrot (2013, pre-designation of reserve)" as a comparable example.

Citing this article

Rehberg, C. (2019). Prospective Tasmanian Tiger tracks found in Tasmania, Accessed: date, http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au.

References

Bailey, C. (2006). Tiger photos - the real story. Available from https://tasmaniantimes.com/2006/04/tiger-photos-the-real-story/. Accessed 1 Jul 2019.

Burbidge, A.A. & Woinarski, J. (2016). Thylacinus cynocephalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21866A21949291. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T21866A21949291.en. Downloaded on 01 July 2019.

Campbell, C. R. (undated A). "The Thylacine Museum - Expeditions and Searches - 1937 to Present Day". Available from http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/expeditions/expeditions_and_searches_9.htm. Accessed 1 Jul 2019.

Campbell, C. R. (undated B). "The Thylacine Museum - Biology - Behaviour". Available from http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/behaviour/behaviour_10.htm. Accessed 13 Aug 2019.

Campbell, C. R. (undated C)."The Thylacine in Captivity: The Historical Thylacine Films". Available from http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/captivity/films/films.htm. Accessed 2 Jun 2019.

Department of the Environment (2019). Thylacinus cynocephalus in Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment, Canberra. Available from: http://www.environment.gov.au/sprat. Accessed Mon, 1 Jul 2019 12:59:01 +1000.

Guiler, E. R. (1985) Thylacine, Tragedy of the Tasmanian Tiger. Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

Moeller, H. (1997). Der Beutelwolf, Thylacinus cynocephalus. Magdeburg, Germany: Westarp Wissenschaften.

Mooney, N. (1984). Tasmanian Tiger Sighting Casts Marsupial in New Light, Australian Natural History Vol. 21 No. 5, Winter 1984. Available from https://media.australianmuseum.net.au/media/dd/Uploads/Documents/38355/ams370_vXXI_05_lowres.4989b58.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul 2019.

Mooney, N. (C.1988). Tracks. Unpublished, Hobart. In the archives of Heinz Moeller.

Parks & Wildlife Service Tasmania (undated). Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger, Thylacinus cynocephalus. Available from https://www.parks.tas.gov.au/?base=4765. Accessed 1 Jul 2019.

Parrot, M. (2017). Via Twitter. Available from https://twitter.com/drmparrott/status/830385243882344449. Accessed 13 Aug 2019.

Rehberg, C. (undated A). About the author. Available from http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au/about-wlmd/about-the-author/. Accessed 1 Jul 2019.

Rehberg, C. (undated B). Examining the evidence. Available from http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au/examining-the-evidence/. Accessed 2 Jul 2019.

Rehberg, C. (undated C). Press. Available from http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au/press/. Accessed 2 Jul 2019.

Rehberg, C. (undated D). Expeditions. Available from http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au/expeditions/. Accessed 2 Jul 2019.

Rehberg, C. (undated E). Animal tracks library. Available from http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au/research/topical/animal-tracks-library/. Accessed 13 Aug 2019.

Rehberg, C. (2006). Doyle thylacine - high resolution analysis. Available from http://www.wherelightmeetsdark.com.au/examining-the-evidence/tasmanian-tiger-(thylacine)/doyle-thylacine/doyle-thylacine-high-resolution-analysis/#Doylethylacine-highresolutionanalysis-TheMPEGfileformat. Accessed 28 OCt 2019.

Sleightholme, S. R. & Ayliffe, N. International Thylacine Specimen Database (4th revision). CD-Rom. Master Copy: Zoological Society, London, 2011 (4th revision).

Towie, Narelle (2011). Thylacine footprints found in Augusta's Jewel Cave, Accessed: 13 Aug 2019, https://www.perthnow.com.au/news/wa/thylacine-footprints-found-in-augustas-jewel-cave-ng-253820b33994dc5783c4958c9fc29bdb

Triggs, B. (1984). Mammal Tracks and Signs: A Fieldguide for South-Eastern Australia.

Tulloch, Ayesha & Auerbach, Nancy & Avery-Gomm, Stephanie & Bayraktarov, Elisa & Butt, Nathalie & Dickman, Christopher & Ehmke, Glenn & Fisher, Diana & Grantham, Hedley & Holden, Matthew & Lavery, Tyrone & Leseberg, Nicholas & Nicholls, Miles & O'Connor, James & Roberson, Leslie & Smyth, Anita & Stone, Zoë & Tulloch, Vivitskaia & Turak, Eren & Watson, James. (2018). A decision tree for assessing the risks and benefits of publishing biodiversity data. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2. 10.1038/s41559-018-0608-1.

Addendum

Following publication of this article, a number of people have contributed additional material relating to the walking gait and tracks left by Tasmanian Devils. In short, the Tasmanian Devil can be seen to place its hind foot forward of where its front foot was placed. This means according to all measures considered below, an explanation of Tasmanian Devil is equally as likely as Tasmanian Tiger. Given the lack of definitive evidence of the persistence of the Tasmanian Tiger, the conclusion must be that more likely than not, these tracks were left by a Tasmanian Devil. The analysis has led to a number of important realisations regarding the tracking of Tasmanian Devils and Thylacines, with implications for tracking all species. In due course a new article will re-visit and summarise the insights gleaned below, together with the information gained from the newly submitted materials. When that article is complete, this article will be updated to announce it. (This note added 6 Nov 2019).